How China views US nuclear policy

By Thomas Fingar | May 20, 2011

A year ago the Obama administration released its congressionally mandated Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) on the role of nuclear weapons in defending the United States and its allies and partners. Defense planners and national security specialists around the globe eagerly awaited the report to see how it would embody the president’s commitment to reducing the role of nuclear weapons in US strategy, and how it would differ from the strategy prepared by the Bush administration in 2001. Reactions ranged from praise for the NPR’s content and the consultations that had preceded its publication, to discomfort about its implications for specific countries and strategic stability, to dismissal of its significance for nuclear disarmament. Chinese experts acknowledged a number of positive developments but devoted more attention to the report’s negative implications for China.

Commentators from China’s still-small community of academics and military officers who follow strategic issues generally welcomed the reduction of US nuclear inventories and reliance on nuclear weapons, the commitment to seek ratification of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, and a number of other specific changes to the US nuclear posture. Most of these experts, however, continue to view American nuclear policy with suspicion. This reaction is the product of both a general phenomenon that one leading scholar of US-China relations calls strategic mistrust, and factors specific to the release of the NPR. Those factors include timing, concerns about the implications for China’s deterrent capability, and the absence of prior consultation.

Bad timing. The tone, and to some extent the content, of Chinese commentaries was influenced by the fact that the Nuclear Posture Review was released when US-China relations were in one of their periodic downswings. Just weeks earlier, the president had agreed to sell $6.4 billion in arms to Taiwan, and had received the Dalai Lama at the White House. The Obama administration was pressing China to revalue its currency, and pushing for stronger sanctions against Iran and North Korea, which China resisted. This was occurring in the context of US efforts to strengthen relations with Japan and South Korea. When US-China relations are good, leaders in Beijing see value in America’s alliances with Japan and South Korea, because extended deterrence has persuaded those neighbors to eschew nuclear weapons. But when US-China relations are tense, China views these alliances as threats.

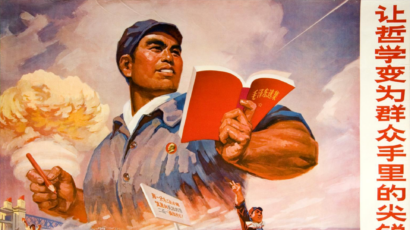

Strategic mistrust. The suspicion of Obama’s nuclear doctrine has also been aggravated by a Chinese proclivity to see precedents, patterns, and parallels where Americans see unique and unrelated developments. These different predilections often cause Chinese to posit — and to find — deliberate or conspiratorial intent in American bureaucratic maneuvers and budgetary tradeoffs. Many Chinese are inclined to view all US doctrine and actions as part of a concerted effort to contain and constrain China. Americans often compound that problem by assuming that others will automatically see US pronouncements in the same way that they do. The problem is made even worse when revealed or rumored “secret” documents appear to be inconsistent with official public statements. For example, when the classified 2001 Nuclear Posture Review leaked a few months after delivery to the Congress, it was widely construed in China as belying Washington’s proclamations that a strong, stable, and prosperous China was in US interests because it grouped China with North Korea, Iran, Iraq, and other nations considered hostile to the United States.

Although the 2010 review was made public, in part to prevent this kind of miscommunication, many in Beijing scrutinized the Obama NPR for indications of “true” US intentions. Toward this end, commentators and government officials were eager to determine whether elements in the 2001 review that they found particularly worrisome were temporary aberrations or fundamental components of US nuclear strategy. Concerns associated with China’s rise — whether expressed by Americans or imputed by Chinese who suspect it is only a matter of time until the United States attempts to slow or stop China’s ascent — are now a constant subtext in the Sino-US relationship. Both sides contribute to the atmosphere of mutual strategic distrust.

A threat to deterrence. Many Chinese commentators found two aspects of the 2010 NPR to be especially troubling: the importance ascribed by the US to missile defense, and increased US reliance on advanced conventional weapons. Chinese academics and military officers view missile defense as a means for degrading China’s deterrent, and as a threat to strategic stability because it reduces American vulnerability. A number of them interpreted decreased US reliance on nuclear weapons as implying greater reliance on conventional arms, an arena in which the United States enjoys unrivaled superiority. Some described this as a “trap” that would require Beijing to engage in an expensive and potentially ruinous conventional arms race with the United States that would harm China’s image and prospects for continued rapid economic growth.

Even the reductions in American and Russian nuclear forces agreed to in New START and referenced in the NPR were interpreted as intended to put pressure on China to reduce its own nuclear arsenal or to embarrass Beijing by pointing out that it was the only permanent member of the United Nations Security Council that was not reducing its reliance on nuclear weapons. Despite the potential for invidious comparison, however, Chinese preferred being grouped with Russia in the 2010 NPR to being listed with “rogue” nations in the 2001 report.

Talk therapy. Countries will always interpret policy statements like the Nuclear Posture Review in light of broader concerns and relationships, but the reactions of China and several other states indicate clearly that consultation enhances understanding of US intentions, and the absence of consultation fuels misperception and mistrust. This judgment is supported by the findings of researchers from around the world who contributed to the March 2011 special issue of The Nonproliferation Review on foreign reactions to the 2010 NPR. In preparing our country-specific assessments, we interviewed knowledgeable foreign specialists and examined official statements and public commentary. As one might expect, we found that talking with foreign leaders about US strategy, in advance, helps Washington influence policy abroad after such reports are issued. Russia is a prime example: high-level meetings between US and Russian officials during the period leading up to the release of the NPR helped encourage Moscow to adopt a considerably more moderate nuclear policy than it otherwise would have. What’s more, it helped thaw the relationship so that cooperation in other areas is now more likely.

Indeed, on his March trip to Russia, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates observed that the US has now “had underway, for more than 40 years, the kind of dialogue with Russia that I’m just trying to get started with China.” The 2011 National Military Strategy, released in February, emphasizes the need to build a “deeper military-to-military relationship with China to expand areas of mutual interest and benefit, improve understanding, reduce misperception, and prevent miscalculation.” It is a step in the right direction.

China and the United States have regular discussions and “strategic dialogues” on dozens of issues. The most glaring exception is the paucity and erratic character of dialogue on traditional security issues, including military doctrine, strategic systems, and strategic intent. China’s decision to suspend military-to-military talks in response to the Obama administration’s announcement of new arms sales to Taiwan precluded prior consultation on the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review, but the United States has halted this dialogue in the past for other reasons that seem less important than the need for sustained, high-level talks to reduce misperception and strategic distrust. Both sides have too much at stake to allow strategic dialogue to remain hostage to other concerns.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Nuclear Weapons, Opinion