Simulation of soot injected into the atmosphere after a nuclear war between India and Pakistan. (Courtesy Max Tegmark / Future of Life Institute)

October 20, 2022

Design by Thomas Gaulkin

This summer, the New York City Emergency Management department released a new public service announcement on nuclear preparedness, instructing New Yorkers about what to do during a nuclear attack. The 90-second video starts with a woman nonchalantly announcing the catastrophic news: “So there’s been a nuclear attack. Don’t ask me how or why, just know that the big one has hit.” Then the PSA video advises New Yorkers on what to do in case of a nuclear attack: Get inside, stay inside, and stay tuned to media and governmental updates.

But nuclear preparedness works better if you are not in the blast radius of a nuclear attack. Otherwise, there’s no going into your house and closing your doors because the house will be gone. Now imagine there have been hundreds of those “big ones.” That’s what even a “small” nuclear war would include. If you are lucky not to be within the blast radius of one of those, it may not ruin your day, but soon enough, it will ruin your whole life.

Effects of a single nuclear explosion

Any nuclear explosion creates radiation, heat, and blast effects that will result in many quick fatalities.

Direct radiation is the most immediate effect of the detonation of a nuclear weapon. It is produced by the nuclear reactions inside the bomb and comes mainly in the form of gamma rays and neutrons.

Direct radiation lasts less than a second, but its lethal level can extend over a mile in all directions from the detonation point of a modern-day nuclear weapon with an explosive yield equal to the effect of several hundred kilotons of TNT.

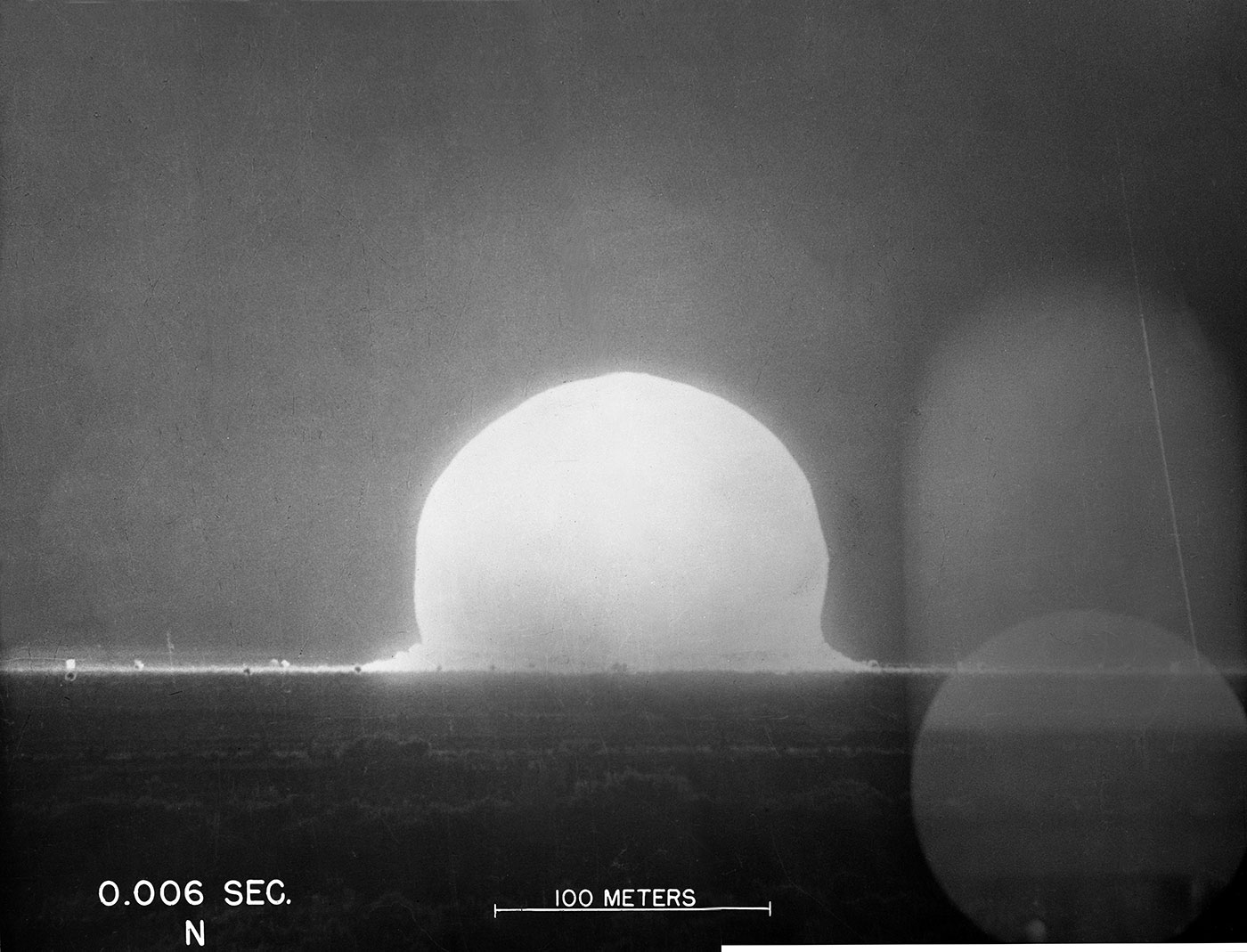

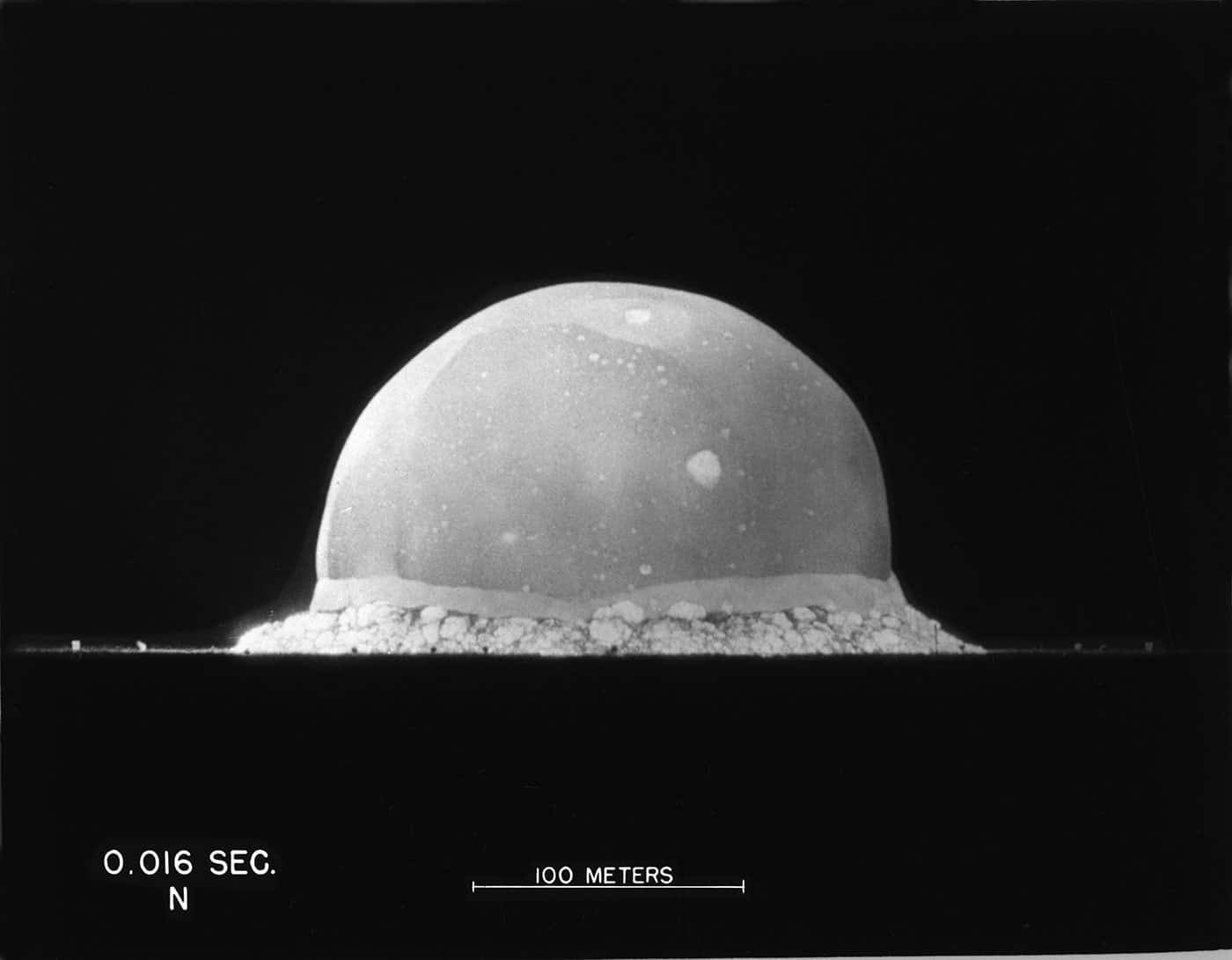

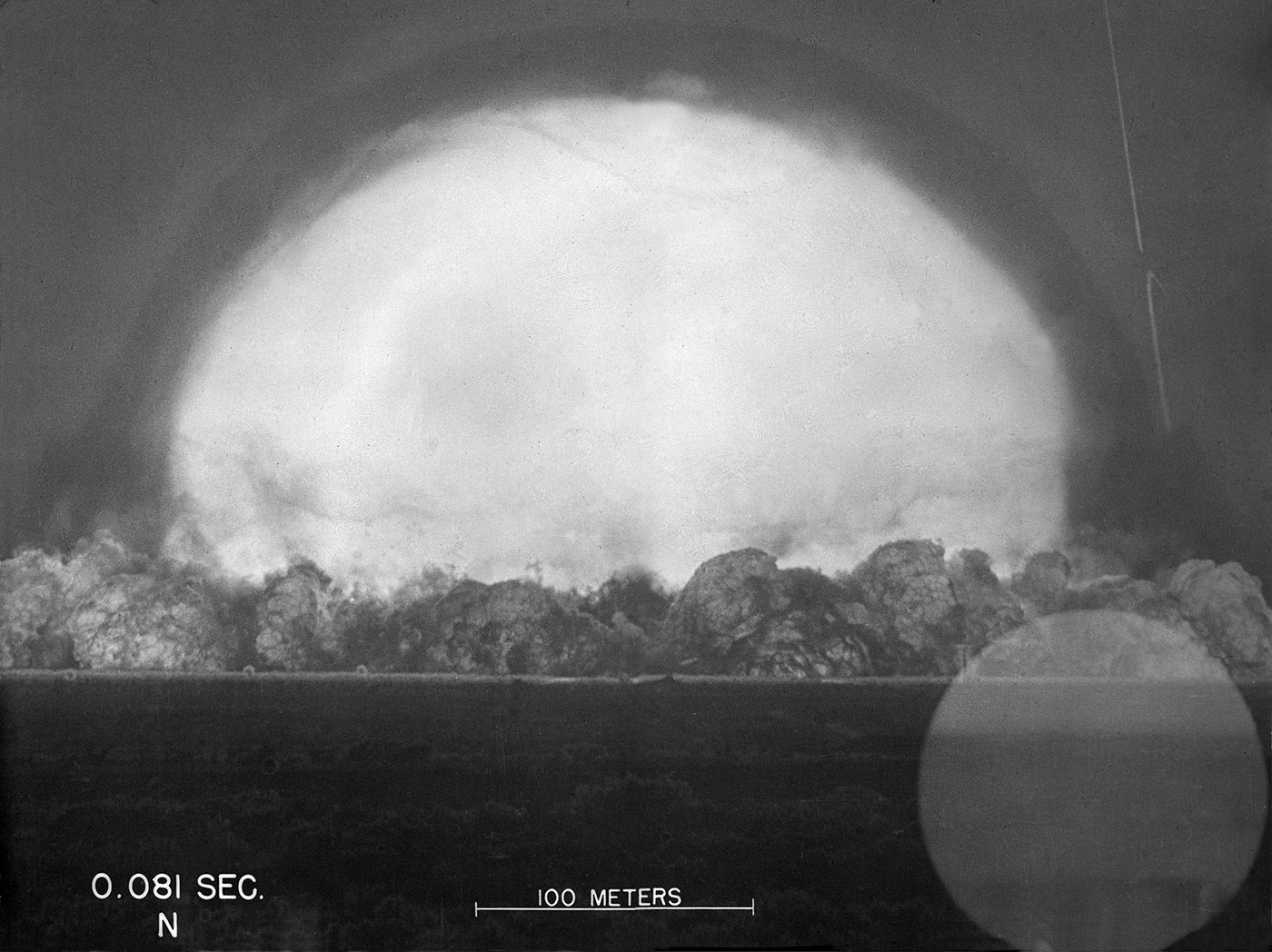

Photos from the first second of the Trinity test shot, the first nuclear explosion on Earth. (Los Alamos National Laboratory)

Microseconds into the explosion of a nuclear weapon, energy released in the form of X-rays heats the surrounding environment, forming a fireball of superheated air. Inside the fireball, the temperature and pressure are so extreme that all matter is rendered into a hot plasma of bare nuclei and subatomic particles, as is the case in the Sun’s multi-million-degree core.

The fireball following the airburst explosion of a 300-kiloton nuclear weapon—like the W87 thermonuclear warhead deployed on the Minuteman III missiles currently in service in the US nuclear arsenal—can grow to more than 600 meters (2,000 feet) in diameter and stays blindingly luminous for several seconds, before its surface cools.

The light radiated by the fireball’s heat—accounting for more than one-third of the thermonuclear weapon’s explosive energy—will be so intense that it ignites fires and causes severe burns at great distances. The thermal flash from a 300-kiloton nuclear weapon could cause first-degree burns as far as 13 kilometers (8 miles) from ground zero.

Then comes the blast wave.

The blast wave—which accounts for about half the bomb’s explosive energy—travels initially faster than the speed of sound but slows rapidly as it loses energy by passing through the atmosphere.

Because the radiation superheats the atmosphere around the fireball, air in the surroundings expands and is pushed rapidly outward, creating a shockwave that pushes against anything along its path and has great destructive power.

The destructive power of the blast wave depends on the weapon’s explosive yield and the burst altitude.

Film footage from the Apple 2 / Cue nuclear test shot on May 5, 1955, part of the Operation Teapot series.

An airburst of a 300-kiloton explosion would produce a blast with an overpressure of over 5 pounds per square inch (or 0.3 atmospheres) up to 4.7 kilometers (2.9 miles) from the target. This is enough pressure to destroy most houses, gut skyscrapers, and cause widespread fatalities less than 10 seconds after the explosion.

Radioactive fallout

Shortly after the nuclear detonation has released most of its energy in the direct radiation, heat, and blast, the fireball begins to cool and rise, becoming the head of the familiar mushroom cloud. Within it is a highly-radioactive brew of split atoms, which will eventually begin to drop out of the cloud as it is blown by the wind. Radioactive fallout, a form of delayed radioactivity, will expose post-war survivors to near-lethal doses of ionizing radiation.

As for the blast, the severity of the fallout contamination depends on the fission yield of the bomb and its height of burst. For weapons in the hundreds of kilotons, the area of immediate danger can encompass thousands of square kilometers downwind of the detonation site. Radiation levels will be initially dominated by isotopes of short half-lives, which are the most energetic and so most dangerous to biological systems. The acutely lethal effects from the fallout will last from days to weeks, which is why authorities recommend staying inside for at least 48 hours, to allow radiation levels to decrease.

Because its effects are relatively delayed, estimating casualties from the fallout is difficult; the number of deaths and injuries will depend very much on what actions people take after an explosion. But in the vicinity of an explosion, buildings will be completely collapsed, and survivors will not be able to shelter. Survivors finding themselves less than 460 meters (1,500 feet) from a 300-kiloton nuclear explosion will receive an ionizing radiation dose of 500 Roentgen equivalent man (rem). “It is generally believed that humans exposed to about 500 rem of radiation all at once will likely die without medical treatment,” the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission says.

But at a distance so close to ground zero, a 300-kiloton nuclear explosion would almost certainly burn and crush to death any human being. The higher the nuclear weapon’s yield, the smaller the acute radiation zone is relative to its other immediate effects.

One detonation of a modern-day, 300-kiloton nuclear warhead—that is, a warhead nearly 10 times the power of the atomic bombs detonated at Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined—on a city like New York would lead to over one million people dead and about twice as many people with serious injuries in the first 24 hours after the explosion. There would be almost no survivors within a radius of several kilometers from the explosion site.

1,000,000

deaths after 24 hours

Immediate effects of nuclear war

Excerpt from “Plan A” a video simulation of an escalatory nuclear war between the United States and Russia. (Alex Glaser / Program on Science and Global Security, Princeton University)

In a nuclear war, hundreds or thousands of detonations would occur within minutes of each other.

Regional nuclear war between India and Pakistan that involved about 100 15-kiloton nuclear weapons launched at urban areas would result in 27 million direct deaths.

27,000,000

deaths from regional war

A global all-out nuclear war between the United States and Russia with over four thousand 100-kiloton nuclear warheads would lead, at minimum, to 360 million quick deaths.* That’s about 30 million people more than the entire US population.

360,000,000

deaths from global war

* This estimate is based on a scenario of an all-out nuclear war between Russia and the United States involving 4,400 100-kiloton weapons under the 2002 Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty (SORT) limits, where each country can deploy up to 2,200 strategic warheads. The 2010 New START Treaty further limits the US- and Russian-deployed long-range nuclear forces down to 1,550 warheads. But as the average yield of today’s strategic nuclear forces of Russia and the United States far exceeds 100 kilotons, a full nuclear exchange between the two countries involving around 3,000 weapons likely would result in similar direct casualties and soot emissions.

A global all-out nuclear war between the United States and Russia with over four thousand 100-kiloton nuclear warheads would lead, at minimum, to 360 million quick deaths.* That’s about 30 million people more than the entire US population.

360,000,000

deaths from global war

* This estimate is based on a scenario of an all-out nuclear war between Russia and the United States involving 4,400 100-kiloton weapons under the 2002 Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty (SORT) limits, where each country can deploy up to 2,200 strategic warheads. The 2010 New START Treaty further limits the US- and Russian-deployed long-range nuclear forces down to 1,550 warheads. But as the average yield of today’s strategic nuclear forces of Russia and the United States far exceeds 100 kilotons, a full nuclear exchange between the two countries involving around 3,000 weapons likely would result in similar direct casualties and soot emissions.

In an all-out nuclear war between Russia and the United States, the two countries would not limit to shooting nuclear missiles at each other’s homeland but would target some of their weapons at other countries, including ones with nuclear weapons. These countries could launch some or all their weapons in retaliation.

Together, the United Kingdom, China, France, Israel, India, Pakistan, and North Korea currently have an estimated total of over 1,200 nuclear warheads.

As horrific as those statistics are, the tens to hundreds of millions of people dead and injured within the first few days of a nuclear conflict would only be the beginnings of a catastrophe that eventually will encompass the whole world.

Global climatic changes, widespread radioactive contamination, and societal collapse virtually everywhere could be the reality that survivors of a nuclear war would contend with for many decades.

Two years after any nuclear war—small or large—famine alone could be more than 10 times as deadly as the hundreds of bomb blasts involved in the war itself.

The only color photograph of the Trinity nuclear test on July 16, 1945. (Jack Aeby / Los Alamos National Laboratory)

In recent years, in some US military and policy circles, there has been a growing perception that a limited nuclear war can be fought and won. Many experts believe, however, that a limited nuclear war is unlikely to remain limited. What starts with one tactical nuclear strike or a tit-for-tat nuclear exchange between two countries could escalate to an all-out nuclear war ending with the immediate and utter destruction of both countries.

But the catastrophe will not be limited to those two belligerents and their allies.

The long-term regional and global effects of nuclear explosions have been overshadowed in public discussions by the horrific, obvious, local consequences of nuclear explosions. Military planners have also focused on the short-term effects of nuclear explosions because they are tasked with estimating the capabilities of nuclear forces on civilian and military targets. Blast, local radiation fallout, and electromagnetic pulse (an intense burst of radio waves that can damage electronic equipment) are all desired outcomes of the use of nuclear weapons—from a military perspective.

But widespread fires and other global climatic changes resulting from many nuclear explosions may not be accounted for in war plans and nuclear doctrines. These collateral effects are difficult to predict; assessing them requires scientific knowledge that most military planners don’t possess or take into account. Yet, in the few years following a nuclear war, such collateral damage may be responsible for the death of more than half of the human population on Earth.

Global climatic changes

Since the 1980s, as the threat of nuclear war reached new heights, scientists have investigated the long-term, widespread effects of nuclear war on Earth systems. Using a radiative-convective climate model that simulates the vertical profile of atmospheric temperatures, American scientists first showed that a nuclear winter could occur from the smoke produced by the massive forest fires ignited by nuclear weapons after a nuclear war. Two Russian scientists later conducted the first three-dimensional climate modeling showing that global temperatures would drop lower on land than on oceans, potentially causing an agricultural collapse worldwide. Initially contested for its imprecise results due to uncertainties in the scenarios and physical parameters involved, nuclear winter theory is now supported by more sophisticated climate models. While the basic mechanisms of nuclear winter described in the early studies still hold today, most recent calculations have shown that the effects of nuclear war would be more long-lasting and worse than previously thought.

A huge cloud resulting from the massive fires caused by “Little Boy”—the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Japan on August 6, 1945—a few hours after the initial explosion. (US Army)

Stratospheric soot injection

The heat and blast from a thermonuclear explosion are so powerful they can initiate large-scale fires in both urban and rural settings. A 300-kiloton detonation in a city like New York or Washington DC could cause a mass fire with a radius of at least 5.6 kilometers (3.5 miles), not altered by any weather conditions. Air in that area would be turned into dust, fire, and smoke.

But a nuclear war will set not just one city on fire, but hundreds of them, all but simultaneously. Even a regional nuclear war—say between India and Pakistan—could lead to widespread firestorms in cities and industrial areas that would have the potential to cause global climatic change, disrupting every form of life on Earth for decades.

Smoke from mass fires after a nuclear war could inject massive amounts of soot into the stratosphere, the Earth’s upper atmosphere. An all-out nuclear war between India and Pakistan, with both countries launching a total of 100 nuclear warheads of an average yield of 15 kilotons, could produce a stratospheric loading of some 5 million tons (or teragrams, Tg) of soot. This is about the mass of the Great Pyramid of Giza, pulverized and turned into superheated dust.

A simulation of the vertically averaged smoke optical depth in the first 54 days after a nuclear war between India and Pakistan. (Robock et al., Atmos. Chem. Phys., 7, 2003–2012, 2007)

But these lower-end estimates date back to the late 2000s. Since then, India and Pakistan have significantly expanded their nuclear arsenals, both in the number of nuclear warheads and yield. By 2025, India and Pakistan could have up to 250 nuclear weapons each, with yields of 12 kilotons on the low end, up to a few hundred kilotons. A nuclear war between India and Pakistan with such arsenals could send up to 47 Tg of soot into the stratosphere.

For comparison, the recent catastrophic forest fires in Canada in 2017 and Australia in 2019 and 2020 produced 0.3 Tg and 1 Tg of smoke respectively. Chemical analysis showed, however, that only a small percentage of the smoke from these fires was pure soot—0.006 and 0.02 Tg respectively. This is because only wood was burning. Urban fires following a nuclear war would produce more smoke, and a higher fraction would be soot. But these two episodes of massive forest fires demonstrated that when smoke is injected into the lower stratosphere, it is heated by sunlight and lofted at high altitudes—10 to 20 kilometers (33,000 to 66,000 feet)—prolonging the time it stays in the stratosphere. This is precisely the mechanism that now allows scientists to better simulate the long-term impacts of nuclear war. With their models, researchers were able to accurately simulate the smoke from these large forest fires, further supporting the mechanisms that cause nuclear winter.

The climatic response from volcanic eruptions also continues to serve as a basis for understanding the long-term impacts of nuclear war. Volcanic blasts typically send ash and dust up into the stratosphere where it reflects sunlight back into space, resulting in the temporary cooling of the Earth’s surface. Likewise, in the theory of nuclear winter, the climatic effects of a massive injection of soot aerosols into the stratosphere from fires following a nuclear war would lead to the heating of the stratosphere, ozone depletion, and cooling at the surface under this cloud. Volcanic eruptions are also useful because their magnitude can match—or even surpass—the level of nuclear explosions. For instance, the 2022 Hunga Tonga’s underwater volcano released an explosive energy of 61 megatons of TNT equivalent—more than the Tsar Bomba, the largest human-made explosion in history with 50 Mt. Its plume reached altitudes up to about 56 kilometers (35 miles), injecting well over 50 Tg—even up to 146 Tg—of water vapor into the stratosphere where it will stay for years. Such a massive injection of stratospheric water could temporarily impact the climate—although differently than soot.

Aerial footage of the 2022 Hunga Tonga volcanic eruption. The vapor plume reached altitudes up to 56 kilometers (35 miles) and injected more than 50 teragrams of water vapor into the stratosphere. (Tonga Geological Services via YouTube)

Since Russia’s war in Ukraine started, President Putin and other Russian officials have made repeated nuclear threats, in an apparent attempt to deter Western countries from any direct military intervention. If Russia were to ever start—voluntarily or accidentally—nuclear war with the United States and other NATO countries, the number of devastating nuclear explosions involved in a full exchange could waft more than 150 Tg of soot into the stratosphere, leading to a nuclear winter that would disrupt virtually all forms of life on Earth over several decades.

Stratospheric soot injections associated with different nuclear war scenarios would lead to a wide variety of major climatic and biogeochemical changes, including transformations of the atmosphere, oceans, and land. Such global climate changes will be more long-lasting than previously thought because models of the 1980s did not adequately represent the stratospheric plume rise. It is now understood that soot from nuclear firestorms would rise much higher into the stratosphere than once imagined, where soot removal mechanisms in the form of “black rains” are slow. Once the smoke is heated by sunlight it can self-loft to altitudes as high as 80 kilometers (50 miles), penetrating the mesosphere.

A simulation of the vertically averaged smoke optical depth in the first 54 days after a nuclear war between Russia and the United States. (Alan Robock)

Changes in the atmosphere

After soot is injected into the upper atmosphere, it can stay there for months to years, blocking some direct sunlight from reaching the Earth’s surface and decreasing temperatures. At high altitudes—20 kilometers (12 miles) and above near the equator and 7 kilometers (4.3 miles) at the poles—the smoke injected by nuclear firestorms would also absorb more radiation from the sun, heating the stratosphere and perturbing stratospheric circulation.

In the stratosphere, the presence of highly absorptive black carbon aerosols would result in considerably enhanced stratospheric temperatures. For instance, in a regional nuclear war scenario that leads to a 5-Tg injection of soot, stratospheric temperatures would remain elevated by 30 degrees Celsius after four years.

The extreme heating observed in the stratosphere would increase the global average loss of the ozone layer—which protects humans and other life on Earth from the severe health and environmental effects of ultraviolet radiation—for the first few years after a nuclear war. Simulations have shown that a regional nuclear war that lasted three days and injected 5 Tg of soot into the stratosphere would reduce the ozone layer by 25 percent globally; recovery would take 12 years. A global nuclear war injecting 150 Tg of stratospheric smoke would cause a 75 percent global ozone loss, with the depletion lasting 15 years.

Changes on land

Soot injection in the stratosphere will lead to changes on the Earth’s surface, including the amount of solar radiation that is received, air temperature, and precipitation.

The loss of the Earth’s protective ozone layer would result in several years of extremely high ultraviolet (UV) light at the surface, a hazard to human health and food production. Most recent estimates indicate that the ozone loss after a global nuclear war would lead to a tropical UV index above 35, starting three years after the war and lasting for four years. The US Environmental Protection Agency considers a UV index of 11 to pose an “extreme” danger; 15 minutes of exposure to a UV index of 12 causes unprotected human skin to experience sunburn. Globally, the average sunlight in the UV-B range would increase by 20 percent. High levels of UV-B radiation are known to cause sunburn, photoaging, skin cancer, and cataracts in humans. They also inhibit the photolysis reaction required for leaf expansion and plant growth.

Smoke lofted into the stratosphere would reduce the amount of solar radiation making it to Earth’s surface, reducing global surface temperatures and precipitation dramatically.

Even a nuclear exchange between India and Pakistan—causing a relatively modest stratospheric loading of 5 Tg of soot—could produce the lowest temperatures on Earth in the past 1,000 years—temperatures below the post-medieval Little Ice Age. A regional nuclear war with 5-Tg stratospheric soot injection would have the potential to make global average temperatures drop by 1 degree Celsius.

Even though their nuclear arsenals have been cut in size and average yield since the end of the Cold War, a nuclear exchange between the United States and Russia would still likely initiate a much more severe nuclear winter, with much of the northern hemisphere facing below-freezing temperatures even during the summer. A global nuclear war that injected 150 Tg of soot into the stratosphere could make temperatures drop by 8 degrees Celsius—3 degrees lower than Ice Age values.

In any nuclear war scenario, the temperature changes would have their greatest effect on mid- and high-latitude agriculture, by reducing the length of the crop season and the temperature even during that season. Below-freezing temperatures could also lead to a significant expansion of sea ice and terrestrial snowpack, causing food shortages and affecting shipping to crucial ports where sea ice is not now a factor.

Global average precipitation after a nuclear war would also drop significantly because the lower amounts of solar radiation reaching the surface would reduce temperatures and water evaporation rates. The precipitation decrease would be the greatest in the tropics. For instance, even a 5-Tg soot injection would lead to a 40 percent precipitation decrease in the Asian monsoon region. South America and Africa would also experience large drops in rainfall.

Changes in the ocean

The longest-lasting consequences of any nuclear war would involve oceans. Regardless of the location and magnitude of a nuclear war, the smoke from the resulting firestorms would quickly reach the stratosphere and be dispersed globally, where it would absorb sunlight and reduce the solar radiation to the ocean surface. The ocean surface would respond more slowly to changes in radiation than the atmosphere and land due to its higher specific heat capacity (i.e., the quantity of heat needed to raise the temperature per unit of mass).

Global ocean temperature decrease will be the greatest starting three to four years after a nuclear war, dropping by approximately 3.5 degrees Celsius for an India-Pakistan war (that injected 47 Tg of smoke into the stratosphere) and six degrees Celsius for a global US-Russia war (150 Tg). Once cooled, the ocean will take even more time to return to its pre-war temperatures, even after the soot has disappeared from the stratosphere and solar radiation returns to normal levels. The delay and duration of the changes will increase linearly with depth. Abnormally low temperatures are likely to persist for decades near the surface, and hundreds of years or longer at depth. For a global nuclear war (150 Tg), changes in ocean temperature to the Arctic sea-ice are likely to last thousands of years—so long that researchers talk of a “nuclear Little Ice Age.”

Because of the dropping solar radiation and temperature on the ocean surface, marine ecosystems would be highly disrupted both by the initial perturbation and by the new, long-lasting ocean state. This will result in global impacts on ecosystem services, such as fisheries. For instance, the marine net primary production (a measure of the new growth of marine algae, which makes up the base of the marine food web) would decline sharply after any nuclear war. In a US-Russia scenario (150 Tg), the global marine net primary production would be cut almost by half in the months after the war and would remain reduced by 20 to 40 percent for over 4 years, with the largest decreases being in the North Atlantic and North Pacific oceans.

Impacts on food production

Changes in the atmosphere, surface, and oceans following a nuclear war will have massive and long-term consequences on global agricultural production and food availability. Agriculture responds to the length of growing seasons, the temperature during the growing season, light levels, precipitation, and other factors. A nuclear war will significantly alter all of those factors, on a global scale for years to decades.

Using new climate, crop, and fishery models, researchers have now demonstrated that soot injections larger than 5 Tg would lead to mass food shortages in almost all countries, although some will be at greater risk of famine than others. Globally, livestock production and fishing would be unable to compensate for reduced crop output. After a nuclear war, and after stored food is consumed, the total food calories available in each nation will drop dramatically, putting millions at risk of starvation or undernourishment. Mitigation measures—shifts in production and consumption of livestock food and crops, for example—would not be sufficient to compensate for the global loss of available calories.

The aforementioned food production impacts do not account for the long-term direct impacts of radioactivity on humans or the widespread radioactive contamination of food that could follow a nuclear war. International trade of food products could be greatly reduced or halted as countries hoard domestic supplies. But even assuming a heroic action of altruism by countries whose food systems are less affected, trade could be disrupted by another effect of the war: sea ice.

Cooling of the ocean’s surface would lead to an expansion of sea ice in the first years after a nuclear war, when food shortages would be highest. This expansion would affect shipping into crucial ports in regions where sea ice is not currently experienced, such as the Yellow Sea.

Post-nuclear famine

Number of people and percentage of the population who could die from starvation two years after a nuclear war. Regional nuclear war scenario corresponds to 5Tg of soot produced by 100 15-kiloton nuclear weapons launched between India and Pakistan. Large-scale nuclear war scenario corresponds to 150Tg of soot produced by 4,400 100-kiloton nuclear weapons launched between Russia and the United States. (Source: Xia et al. Nature Food 3, no. 8 (2022): 586-596.)

Regional war

Global war

Nowhere to hide

The impacts of nuclear war on agricultural food systems would have dire consequences for most humans who survive the war and its immediate effects.

The overall global consequences of nuclear war—including both short-term and long-term impacts—would be even more horrific causing hundreds of millions—even billions—of people to starve to death.

Two years after a nuclear war ends, nearly everyone might face starvation.

There is nowhere to hide.

References & Acknowledgments

This article is based on the work of many researchers who have studied the impacts of nuclear war since the 1980s. The author wishes to thank in particular Alex Glaser from Princeton University, Alan Robock from Rutgers University, and Alex Wellerstein from the Stevens Institute of Technology.

- Aleksandrov, Vladimir V., and Georgiy L. Stenchikov. “On the modelling of the climatic consequences of the nuclear war.” In The Proceeding on Applied Mathematics (1983), 21 pp. Moscow: Computing Centre, USSR Academy of Sciences. http://climate.envsci.rutgers.edu/pdf/AleksandrovStenchikov.pdf

- Bardeen, Charles G., Douglas E. Kinnison, Owen B. Toon, Michael J. Mills, Francis Vitt, Lili Xia, Jonas Jägermeyr et al. "Extreme ozone loss following nuclear war results in enhanced surface ultraviolet radiation." Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 126, no. 18 (2021): e2021JD035079. http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2021JD035079

- Bele, Jean. M. “Nuclear Weapons Effects Simulator”, Nuclear Weapons Education Project, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. https://nuclearweaponsedproj.mit.edu/Node/103

- Coupe, Joshua, Charles G. Bardeen, Alan Robock, and Owen B. Toon. "Nuclear winter responses to nuclear war between the United States and Russia in the whole atmosphere community climate model version 4 and the Goddard Institute for Space Studies ModelE." Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 124, no. 15 (2019): 8522-8543. http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2019JD030509

- Eden, Lynn. Whole world on fire: Organizations, knowledge, and nuclear weapons devastation. Cornell University Press, 2004.

- Glaser, Alex. “Plan A”. Program on Science & Global Security, Princeton University. https://sgs.princeton.edu/the-lab/plan-a

- Harrison, Cheryl S., Tyler Rohr, Alice DuVivier, Elizabeth A. Maroon, Scott Bachman, Charles G. Bardeen, Joshua Coupe et al. "A new ocean state after nuclear war." AGU Advances 3, no. 4 (2022): e2021AV000610. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021AV000610

- Kataria, Sunita, Anjana Jajoo, and Kadur N. Guruprasad. "Impact of increasing Ultraviolet-B (UV-B) radiation on photosynthetic processes." Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology 137 (2014): 55-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2014.02.004

- Kristensen, Hans M., and Matt Korda. “Russian nuclear weapons, 2022.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 78, no. 2 (2022a): 98-121. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2022.2038907

- Kristensen, Hans M., and Matt Korda. “United States nuclear weapons, 2022.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 78, no. 3 (2022b): 162-184. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2022.2062943

- MacKie, R. M. "Effects of ultraviolet radiation on human health." Radiation Protection Dosimetry 91, no. 1-3 (2000): 15-18. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.rpd.a033186

- Millan, Luis, Michelle L. Santee, Alyn Lambert, Nathaniel J. Livesey, Frank Werner, Michael J. Schwartz, Hugh Charles Pumphrey et al. "The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai Hydration of the Stratosphere." (2022). https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL099381

- Mills, Michael J., Owen B. Toon, Richard P. Turco, Douglas E. Kinnison, and Rolando R. Garcia. "Massive global ozone loss predicted following regional nuclear conflict." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105, no. 14 (2008): 5307-5312. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0710058105

- Robock, Alan. "Volcanic eruptions and climate." Reviews of geophysics 38, no. 2 (2000): 191-219. https://doi.org/10.1029/1998RG000054

- Robock, Alan. "The latest on volcanic eruptions and climate." Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union 94, no. 35 (2013): 305-306. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013EO350001

- Robock, Alan, Luke Oman, and Georgiy L. Stenchikov. "Nuclear winter revisited with a modern climate model and current nuclear arsenals: Still catastrophic consequences." Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 112, no. D13 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JD008235

- Robock, Alan, Luke Oman, Georgiy L. Stenchikov, Owen B. Toon, Charles Bardeen, and Richard P. Turco. "Climatic consequences of regional nuclear conflicts." Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 7, no. 8 (2007): 2003-2012. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-7-2003-2007

- Robock, Alan, and Owen B. Toon. "Local nuclear war, global suffering." Scientific American 302, no. 1 (2010): 74-81. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26001848

- Rogers, Jessica, Hans M. Kristensen, and Matt Korda. “The long view: strategic arms control after the New START Treaty.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Forthcoming November 2022.

- Teller, Edward. "Widespread after-effects of nuclear war." Nature 310, no. 5979 (1984): 621-624. https://doi.org/10.1038/310621a0

- Toon, Owen B., Charles G. Bardeen, Alan Robock, Lili Xia, Hans Kristensen, Matthew McKinzie, Roy J. Peterson, Cheryl S. Harrison, Nicole S. Lovenduski, and Richard P. Turco. "Rapidly expanding nuclear arsenals in Pakistan and India portend regional and global catastrophe." Science Advances 5, no. 10 (2019): eaay5478. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aay5478

- Toon, Owen B., Alan Robock, and Richard P. Turco. "Environmental consequences of nuclear war." Physics Today 61, no. 12 (2008): 37. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3047679

- Toon, Owen B., Richard P. Turco, Alan Robock, Charles Bardeen, Luke Oman, and Georgiy L. Stenchikov. "Atmospheric effects and societal consequences of regional scale nuclear conflicts and acts of individual nuclear terrorism." Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 7, no. 8 (2007): 1973-2002. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-7-1973-2007

- Turco, Richard P., Owen B. Toon, Thomas P. Ackerman, James B. Pollack, and Carl Sagan. "Nuclear winter: Global consequences of multiple nuclear explosions." Science 222, no. 4630 (1983): 1283-1292. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.222.4630.1283

- Vömel, Holger, Stephanie Evan, and Matt Tully. "Water vapor injection into the stratosphere by Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai." Science 377, no. 6613 (2022): 1444-1447. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abq2299

- Wellerstein, Alex. “NUKEMAP v.2.72”. Available at: https://nuclearsecrecy.com/nukemap/

- Wolfson, Richard, and Ferenc Dalnoki-Veress. “13: Effects of Nuclear Weapons.” In Nuclear Choices for the Twenty-First Century: A Citizen's Guide. (MIT Press, 2021): 281-304. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/11993.003.0017

- Xia, Lili, Alan Robock, Kim Scherrer, Cheryl S. Harrison, Benjamin Leon Bodirsky, Isabelle Weindl, Jonas Jägermeyr, Charles G. Bardeen, Owen B. Toon, and Ryan Heneghan. "Global food insecurity and famine from reduced crop, marine fishery and livestock production due to climate disruption from nuclear war soot injection." Nature Food 3, no. 8 (2022): 586-596. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-022-00573-0

- Yu, Pengfei, Owen B. Toon, Charles G. Bardeen, Yunqian Zhu, Karen H. Rosenlof, Robert W. Portmann, Troy D. Thornberry et al. "Black carbon lofts wildfire smoke high into the stratosphere to form a persistent plume." Science 365, no. 6453 (2019): 587-590. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax1748

As the Russian invasion of Ukraine shows, nuclear threats are real, present, and dangerous

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent, nonprofit media organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Share: [addthis tool="addthis_inline_share_toolbox"]

I must say that I am SICKENED BY THE FACT THAT WE NEED WEAPONS LIKE THESE!!! I WISH THERE WAS A TREATY TO DO AWAY WITH ALL NUCLEAR WEAPONS AND ALL DATA PERTAINING TO NUKES!!!!

The data you need to keep. You would not want to forget just how deadly they are would you?

Still…. You got to laugh eh!

What is there to laugh about?

I love this comment.

Nowhere to hide is bs. There are no nuclear target zones in South America or Africa.

good. you would die of starvation then.

New Zealand and Australia are both shown as having minimal starvation effects.

While Australia is well within the worst case scenarios of the Soot effects New Zealand is on the edge of even the worst case extrapolations of these effects.

Australia will get hit by Boat refugees, but again New Zealand will get minimal “boat refugees”. Quite simply any attempt to get to New Zealand in a half-arsed overloaded boat will see everyone drown.

The only boats like to make it are well supplied vessels carrying modest numbers of people.

Think also about collapsing supply chains. I’m in Canberra, and there’s no likely nuclear target anywhere near here. In a major US-Russia/China nuclear war, the main challenge Australia will face is feeding its own population, plus large numbers of refugees fleeing south from the equatorial regions – plus climate effects. But when supply chains collapse – we lose fuel so can’t get food to the market – and maybe our electric grids collapse too. Its grim here – maybe not to the same extent as the northern hemisphere – but still it won’t be easy for us.

Watch the 1959 version of the movie

”On the Beach”

Try reading the article.

If nuclear war happens I would prefer to die in the initial detonation than deal with the slow death of the aftermath. If I survived the initial blast I would probably just end it and not have to deal with the suffering.

Good. The rest of us will need your resources and you lack mentality to survive anyway.

Your Mom’s basement isn’t the bunker you think it is.

Just waiting for your moment of glory eh?

You can have your survivalist libertarian fantasy. It won’t work out how you imagine though.

“Survive” haha 😀 Where? Are you 12 years old?

Excellent article. The information given is very unfortunate but also very factual. If a global thermonuclear war ever does occur, you don’t want to be a survivor.

We must stop pouring gasoline on the fire in Ukraine. The most important thing we’ll do in our lives is put an end to this war and negotiate a settlement. The binary view of Amercan exceptionalism vs bad scary Putin is going to end us all, including the awful people making money from soldiers and innocents dying. Tactical nuclear strikes are a myth, this article and others like it should be required reading.

Since the US has repudiated or withdrawn from so many of the treaties already negotiated, I see no way anyone would bother to negotiate any new treaties with the US. How could they trust us?

Your assertion that “the US has repudiated or withdrawn from so many treaties,” is inaccurate, overstated, and made without proper context. Sticking to nuclear treaties: (1) the United States withdrew form the INF Treaty AFTER striving for over a decade to get the Russian Federation to return to compliance (the Russians illegally developed and deployed nuclear-armed intermediate-range ground-launched ballistic missiles–GLBMs); (2) the United States issued legal countermeasures effectively suspending certain aspects of the New Strategic Arms Reduction Talks (START) Treaty IN RESPONSE to Russia’s unlawful suspension of treaty, but the US nevertheless remains a Party to the New START Treaty… Read more »

We must end the war in Ukraine. Even if it were a straight case of a greedy Hitler-like demon making a land grab, we should have to bring it to the negotiating table. But it is far more morally complex than that. Kyiv, Washington and NATO as well as Russia have responsibility for this crisis — and its resolution will be negotiated eventually anyway, if we can avoid a nuclear war. By what moral right do we threaten the lives of children in, say, Ecuador or Sri Lanka because of a struggle for dominance among great powers?

To give in to Putin today would be to acquiesce to nothing less than an endless series of similar confrontations and consequent surrenders. It would solve nothing.The world has been warned of the dangers of nuclear weapons since August 1945, and yet the peril persists virtually unabated. Why? As long as nuclear weapons exist, their inevitable use is assured. The only solution is global disarmament, as unlikely as that may be. The ONLY alternative is global catastrophe..

Probably about as accurate as the climate doom predictions that never actually materialize. The plain simple fact is that there are so many variables that cannot be controlled or accounted for that this is all little more than guessing. One thing is for sure: Those who are prepared and determined to survive will on net long outlive those who are unprepated and give up in the face of prophecies of doom like this one. But thats fine, the rest of us will take your resources.

keep collecting those bottle caps and nuka-cola, surely will be useful in a fallout scenario ?

” climate doom predictions that never actually materialize”

snow crab population is down 90% (and is off the menu for the foreseeable future) because of climate change you dolt, but keep believing your right wing denialist news sources. SMDH.

The US southwest is experiencing a 1200 year drought, Pakistan is under water, massive forest fires in NA and Europe, the east coast of Canada has recorded It’s most powerful storm ever, arctic sea ice at lowest levels and so on and so on, and this was all predicted and this clown still would rather indulge his denialist libertarian fantasies rather than face the truth. Sad.

All the more reason to have a “small” nuclear exchange with Russia. That should slow down the global warming a bring things back in balance. President Biden knows what he is doing.

This isn’t Avatar you dolt. 5 billion people would die, including you.

Not to mention the Eastern States of Australia have been underwater pretty much constantly this year. Japanese Encephalitis is a huge concern in NSW.

What a type of life in it’s ( a nuclear war ) aftermath !!! Scavaging and fighting like dogs trying to survive !!!

How’s that any different than the current situation for many folks around the globe today?

What an odd comment.You say these “prophecies of doom” are “false”, but suggest that “those who are prepated (sic)” will survive. But if the prophecies are false, why would you need to be prepated?

Great article. A masterpiece of presentation. Great research and visual is awsome. Is there anyway to send our illustrious world leaders a copy? Don’t forget to include the nuclear wanabes gnawing at the bit to own nukes. Susan Roy wrote a great book on this topic. “Bomboozled: How The U.S. Government Misled Itself and It’s People Into Believing They Could Survive a Nuclear War.” It’s a great read. By the way a quick comment. You forgot all about EMP’s. The war would be over before it even started. Mass starvation would be in the cards from the get-go.

Dear Julius. Thank you for your comment. We did briefly talk about electromagnetic pulse, which would result from high-altitude nuclear explosions. These would be intended for very specific uses, such as on military targets to damage their computers, communication systems, and other electronic equipment. The role, however, such weapons would have to prevent a nuclear war from starting is unclear. Our article focuses on what is known from the possible consequences of thermonuclear weapons launched on strategic targets and urban areas. Best regards, François

Thank you for pointing that out to me. I see it now. Again I say Kudos for such a well written article.

Thanks for this beautifully presented piece. One comment that gives me a sliver of hope: firestorms would be difficult to get going in most northern cities in high income countries. This was evident in the last world war. Allied bombing succeeded in Hamburg (where the word feuersturm was coined), but failed in Berlin. Hiroshima and Tokyo had firestorms, but both had a lot of densely packed wooden buildings. Wouldn’t it be much tougher in Moscow or New York, say, with concrete, iron and brick, built to withstand fire? Then there are the spread-out US suburbs. And wrt forest fires: there… Read more »

what about Dresden?

I agree … Thank You

A nuclear war is the most stupid thing a human being can do, with over 12,000 nukes worldwide with most of them 10 times the power of Hiroshjima en Nagasaki bomb, is erasing planet Earth from the galactic map.

Thank you for this most sobering, unvarnished assessment.

It’s insanity to have weapons capable of this level of destruction. Profoundly disturbing that there are people in charge of these weapons who are threatening to use them.

They must never be used.

America is so dumb for provoking empires like the Soviet Union to nuke America. Instead just let the bad countries slowly go away because that’s what happened a while after the U.S. and Soviets decided not to nuke eachother.

Why? Just Why do we need nuclear weapons? It’s overkill to the highest level. Haven’t we humans learned from Hiroshima and Nagaski? Frightening!

John Gibson: It stopped the war didn’t it? It also saved countless lives if that war had continued.

The Soviet invasion of Japanese-held territory a few days after Hiroshima did as much as the nukes, since the Japanese were afraid of being divided like Korea was and losing the Emperor, so were motivated to surrender to the US first. But also, Japan was starving, isolated by the US Navy, bombed conventionally every night by the USAAF, with no means to continue. Even Curtis LeMay said the A-bombs weren’t really necessary.

Japan had already surrendered. Learn your history.

You learn your history! The invasion of Soviet armies in Japan held China was about to begin, and the Soviets would have fought with as much anger as they did against the Germans, and America was coming up from the South in Okinawa. The bombs, although terrible, were the only thing that made the die hard Japanese go into peace talks.

No the nuclear weapons were simply a useful diplomatic step off point to surrender to avoid the Russian land invasion that had already begun, the nuclear weapons were no worse than the conventional carpet bombing of Japanese cities. The Russians were going to take Japan by force in a land war and the Japanese took this opportunity to capitulate to the west to avoid this. This is all documented and easy to research

Great, no purpose now in making any long term plans….it seems this scenario is and will be inevitable… bye bye human race, nice knowing you

If it ever happens I want to be directly hit by a warhead. No way do I want to survive only to die the slow painful death that follows. Never let a toddler play with matches; never let man have nuclear weapons. Life 101.

ok thanks 🙂 killing myself now

Love the article just wanted to say thank you ?

This reminds me of the “duck and cover” drills we did in elementary school during the 1950s. They actually told us kids that we’d be safe if we hid under our desks.

Colin Meyer: “Duck & Cover” was only meant to protect us from the broken flying glass and other projectiles – not the heat from the blast if it was a direct hit. Besides, if there was a nuclear strike, would the teachers and Nuns want their kids running around outside when it hit? It was by far the best option. In our grammar school, the Nuns had us all go down to the basement cafeteria and stay beneath the tables.

Thank you for the article it was very while explained and informative. Just hope there is a place we can go to and hide. But if one thing won’t kill you the other will. Thank you again . May God be with us.

At least the ice caps would grow from a nuclear winter and give polar bears a better chance….

It’s actually the perfect solution to global warming. An almost immediate effect of cooling, followed by the collapse of human civilization, which is the root cause. It would give the Earth a breather — in a few decades most of the planet would look as rich and wild as the Chernobyl exclusion zone.

It’s hard to argue with that logic, but what a waste of a beautiful opportunity we humans had! More than 50 years ago, we chose poorly and rather than concentrate all our efforts on further developing safe and efficient nuclear power options we continued developing and building WMD. Today we’re spending billions modernizing our weapons, which can’t be used – and barely any government funding of nuclear power development. Imagine if we’d done the opposite and stopped the nuclear weapons programs and instead had built an entire world powered by clean cheap and safe nuclear power. (eg. Molten Salt Reactors… Read more »

If you track all the billionaires mega yachts heading to remote locations all at once, you should assume the position.

The 1959 movie “On The Beach” gives a fairly realistic view of what would happen. While the northern hemisphere is empty of human life, the radioactivity and fallout slowly drifts into the southern hemisphere, finally killing what is left of humanity. A global thermonuclear war is the end of us all.

Yeah I love that movie (and the book, the movie is very accurate to the source material), but it’s grim as hell

There are plenty of sources showing fallout maps worse case, and NONE of them show radioactivity flowing from north to south of the equator. It doesn’t work that way, real life is not the movies.

Does not work that way – there isn’t a lot of inter-mix between northern hemisphere and southern hemisphere weather patterns.

Also, in the novel by Shute, they use cobalt jacketed nukes, which are purposely designed to spread fallout globally. No one deploys such weapons and have not considered doing so since the 1950s.

I don’t believe the ‘On the Beach’ scenario is accurate.

Better active today than radioactive tomorrow (circa 1970)

Great Piece.

I do question the US not starving, Russia not starving, Australia and India not starving. I anticipate the Q theorists, who will one day have their own whack-a-doodle dark web university, to reason that global waring and nuclear winter can easily cancel each other out.

To think there are whack-a-doodles on the internet is much less worrying than to think of nuclear deterrence Warhawks. These folks get a military pension, go right into nuclear weapons manufacture, and get saluted every 4rth of July.

Australia is pretty out of the way and we produce a LOT of food. It’ll suck, but we’re in a less awful position.

Brian Whit. I’m pretty sure thats just for a regional nuclear war. I couldn’t find one country that didnt starve in the map of the global nuclear war.

As Nikita Khrushchev said, in the aftermath of a nuclear war, the living will envy the dead.

Until Germany “nuked” the Berlin Research Reactor as a panic reaction to the Fukushima Catastrophe (WTH… Yeah, talk about German Angst!), I was an active member of Civil Defense here – and I deeply appreciate your excellent, factual information about the “N” in CBRN, combined with equally outstanding visuals – thank you for this masterpiece / article! Now I’d really love to see a similar article addressing the “R” side of things (and, according to experts, a much more likely scenario than N – with regard to “blaming the other party” being possible and “uncertainty of how NATO would respond”… Read more »

To hoard tactical nukes below 100 kilotons is wasteful and should be avoided. Battlefield tactical nukes of under 1,000 kilotons should be built and preserved as highly credible deterrance. Strategic nukes of over 1,000 kilotons should be treasured and kept deployable on outerspace-friendly missiles, to be used within the mesosphere as a climate-control asset to drastically reduce global-warming. So, Bill Gates can be spared of having to think of blocking out the Sun and hatching an artificial sun too for whatever purpose ! LOL !

Where’s my mannequin?!!!

So what you’re saying is in order to stop global warming and reverse it, India and Pakistan need to have an all-out nuclear exchange

What will be the impact of abandoned nuclear power plants in the aftermath of different scenarios discussed in the article? Just for basis of discussion: a 1GWe power plant produces a 5 times greater amount of fission products than the Hiroshima bomb – per day.

Hit the wrong key. Given the collapse of the electrical grid, the cooling ponds would dry. Chernobyl.

This article was similar to the results that I researched during the 1980s while serving as an ICBM launch officer in the US Air Force. The consequences that I could have been responsible for was enough to lead me to resign my commission and leave the Air Force. The one problem with the hypothesis of this article was the yield of the weapons that were used in their calculations. The yields of the weapons on nuclear alert today are many more times more powerful than those used in the hypothesis. An all out nuclear exchange between Russia and the US… Read more »

Not worth it over a regional dispute

Can we pick a day to send all our nukes into the sun?

It would be the perfect solution to curb climate change, only collateral damage has the same consequences as climate change.

The sixth mass extinction once the first explosion is launched, a domino effect impossible to stop, in my humble opinion humanity has an expiration date, by mistake or planning our disappearance is almost a fact.

if you live near an obvious military target u r probably toast. examples are Seattle, SanDiego, Col Springs, Norfolk, JAcksnville, Omaha, etc. I live midway between 2 ANG bases w/tankers, about 60 E of one and 30 W of the other so I’ll get heavy fallout. Cooked.

Mt. Tambora was 33 Gt TNT equivalent, in one place, launching pulverized rock into the stratosphere. It caused the year without a summer. That is our baseline. The nuclear winter scenarios you post here are unrealistic with respect to how a nuclear war would be fought and how easily cities burn.

China, Russia, Britain, the United States and France have agreed that a further spread of nuclear arms and a nuclear war should be avoided, according to a joint statement by the five nuclear powers.

“We affirm that a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought,” the English-language version of the statement read.

The joint statement echoed the words spoken decades earlier by two leaders of nuclear superpowers:

“A nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.”

This statement was first made by Presidents Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev at their summit in Geneva in 1985.

If you add-up all the nuclear tests done over the years, it’s reasonable to postulate that we have been living in a default state of nuclear winter. Slow freeze, slow poison version. This article talks about regional wars involving perhaps 100 warheads in the low-yield range as still having a profound effect. That is perhaps 100-300MT detonated in a short period of time with resulting fires. Consider that 1958 saw approx 102MT of tests done. In 1962, there was 140MT detonated. There has been approximately 60-80MT per year between 1963-1983, falling to less than 40MT after 1985. Many of these… Read more »

Not much optimism when, in the face of all these otherwise terrifying data, the people most likely to push the button believe that god, in some form or another, will protect the chosen. Can’t avoid nuclear war when it’s actually hoped for.

I don’t understand one thing. According to the information above, UV radiation is supposed to increase, but at the same time, the large amount of soot in the atmosphere is supposed to block the sun at least partially. Don’t these two effects work against each other, i.e., the ozone layer is being destroyed, but the increased soot blocks UV radiation?

It’s distressing that the Bulletin uncritically accepts the “science” of nuclear winter. The preponderance of evidence is that atmospheric cooling from even the worst nuclear exchange would be nowhere near as serious as suggested in this article and would be of a relatively short duration. The firestorms that would result from nuclear explosions are the same as any other firestorm. They occur in major bushfires such as those in Australia or Russia. In the Black Summer of 2019-20, ~243,000 square kilometres of forest was burned, much in high-severity (firestorm) fires. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2019%E2%80%9320_Australian_bushfire_season) Numerous pyrocumulonimbus clouds injected about 1 Tg (1 million… Read more »

Jump to comments

↓