The ‘press and pulse’ of climate change strains farmers in Pakistan

By Zafar Imran | February 10, 2023

“Can climate change cause widespread unrest among Pakistan’s farmers, enough to lead to civil conflict, or violence short of it?” Shahbaz Ali, a farmer in Ghotki district in Pakistan’s Sindh province, asked himself when we spoke last year. This was before apocalyptic rains laid waste to millions of acres of Pakistan’s farmland, killing 1,700 people and displacing 7.9 million and causing damage of approximately $30 billion US dollars. Just a few months before the floods, Pakistan’s farmers had already taken a thrashing at the hands of unprecedented and unseasonal high temperatures made 30 times more likely due to climate change.

“I can’t say for sure.”

“But I know,” Ali added, “that every brush with bad luck, be it because of bad weather or not getting a good price for our produce, is making us tighten our belts more and more. Barely anything we do seems to work. After weathering successive losses in their crops, some farmers in my village are at a point where they have to borrow food and money from neighbors and comparatively wealthy farmers just to get by.”

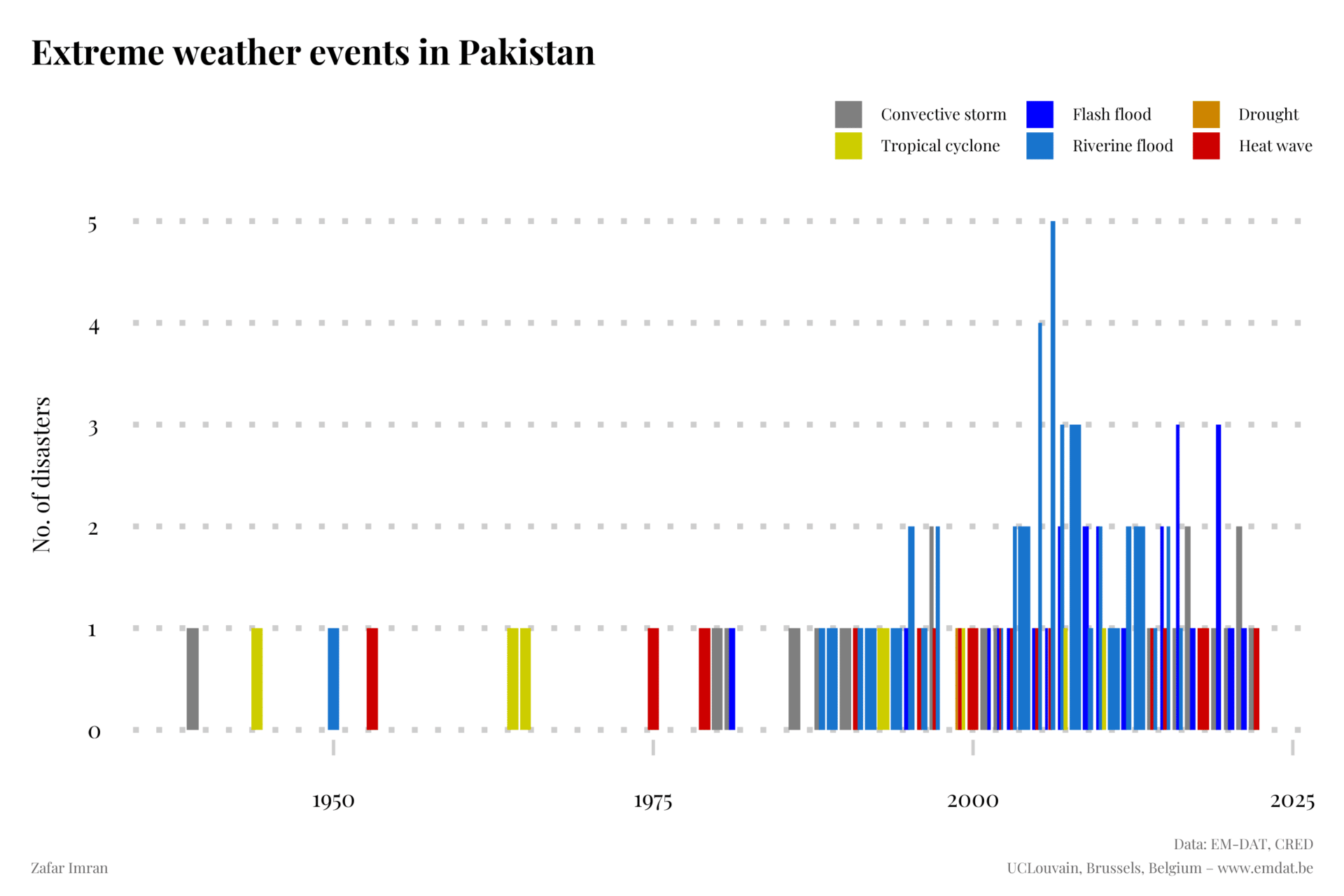

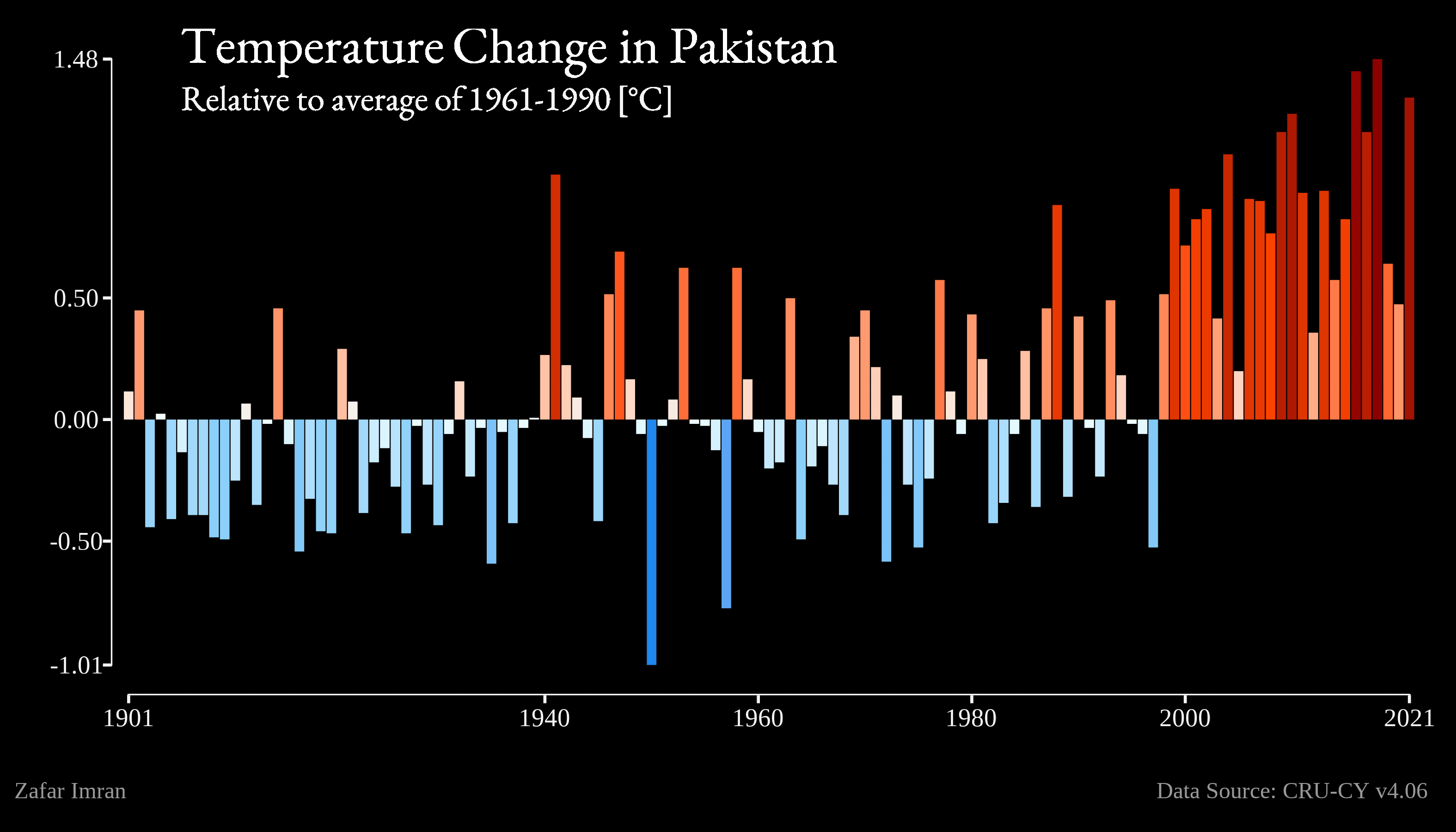

The degree to which climate change will create economic upheaval or even lead to civil conflict around the globe is a question of increasing urgency for researchers and policy practitioners. According to data maintained by the International Disasters Database (EM-DAT), extreme hydrological and meteorological events like drought, extreme temperatures, floods, and storms have increased many times in frequency and severity in Pakistan in the last three decades—from 16 between 1926 and 1990, to 105 between 1991 and 2022. Pakistan’s annual average temperature has increased by 1.68 degrees Celsius between 1901 and 2021, more than the global average temperature increase of 1.1 degrees Celsius.

The deadly combination of the “press and pulse of climate change”—steady and gradual change in climate trends (press) interspersed with unpredictable extreme weather events (pulse)—and the fragile economic system built around it continues to hack at livelihoods, taking down small farmers one blow at a time, trapping some in ever-increasing debt, and forcing the debt-ridden to abandon agriculture altogether and move to cities. Even relatively affluent farmers are desperately trying to stay afloat. The struggle to cope with the new normal is giving way to frustration and unrest.

In hundreds of interviews conducted during my on-going fieldwork through Pakistan’s countryside, farmers have shared their accounts of climate change and variability and effects on their incomes, lifestyles, and livelihoods. Just last year, Samar Aftab, a citrus farmer from village Chak 86-NB—villages in Punjab are named after canals that irrigate them, so Chak 86-NB is Chak or village number 86 situated on the bank of North Branch of the Lower Jhelum Canal—near Sargodha, Punjab, shared his recorded video of a hailstorm in May 2021.

“Hailstorms were never a regular occurrence in our area, let alone in May, which is not the rainy season,” Aftab told me. “The strangest thing was that it was only pellets of ice, some as big as the size of a golf ball, falling out of nowhere, without any rain. Even our animals seemed scared!” Unseasonal and intense hailstorm decimated flowers on the trees in Aftab’s kinnow (a hybrid type of citrus fruit) orchard and slashed his income to a third. This year, instead of unseasonal rains, an unexpected heatwave during the flowering stage of plants, followed by a surprise attack by a mysterious pest, did the trick. “No one in our area could figure out what sort of pest it was, and the pesticides we had on hand didn’t work…. Not only I did not make any money from my orchard this year, but the disease also killed most of my trees,” Aftab said.

Mansoor Gilani, a farmer from Ahmedpur East, near Bahawalpur district in southern Punjab, had a similar story to tell. “My mango crop has failed twice in the last three years. In March 2020, an unseasonal and intense rain of hail made the boor (mango flower) fall off the trees in my mango farm. While in the spring of 2022, a sudden heatwave not only burned the mango flowers but also stunted the growth of wheat and sugarcane crops. The sugarcane yield in my farms plummeted from 1,000 maund (one maund equals 40 kilograms) to barely 250 maund per acre.” As Mansoor was reeling from these back-to-back losses, his cotton crop was hit by an abnormally wet rainy season. “As per my count,” Mansoor continued, “between July 5 and August 31, it rained for 25 days—wiping out almost my entire cotton crop. It was so bad that the teenda (cotton boll) didn’t form on most of the plants.”

Farmers across Punjab and Sindh provinces—the two regions responsible for most of the agriculture in Pakistan—report a conspicuous change in the meteorological calendar. Now, temperatures rise much earlier in the year, and by early spring it is already summer in most parts of the country. Erratic rainfall patterns, both temporally and spatially, are forcing a change in crop patterns. Rains come unexpectedly and dash the hopes of farmers who may be reeling from losses incurred in the previous season. Short but intense winters stunt the growth and reduce the yield of winter crops including wheat, the staple food in the country. The change in diurnal temperatures—the difference between maximum and minimum temperatures in a 24-hours cycle—creates an ambient environment for insects to flourish. There has been a surge of pest attacks—most of them having become immune to pesticides—in addition to outbreaks of many fungal and bacterial plant diseases.

Pakistan’s farmers, battered by the dual threat of short-term yet intense weather events and the drawn-out and sustained change in temperature and precipitation patterns, appear to be at their wit’s end. Guidance from the government is missing too. Weather forecasts are either inaccurate or non-existent. Thus, most decisions vis-à-vis coping responses are taken without complete information about the nature of the stressor and without consideration for the unintended consequences these coping measures may generate for farmers or for the wider political economy.

Imran Sarwar, a farmer from Darya Khan Tehsil in Punjab, shared his frustration about uncertainty that changing weather patterns are producing in farmers’ lives. “We try our best to follow the changed meteorological calendar by chasing planting windows, but the weather has just become unpredictable. There is no telling what might happen next month, next week, or even the next day…. In May 2022, unexpected rain destroyed the cotton seed we had sown just a few days earlier. It takes some time for the seed to germinate and the seedlings to come through the softened/tilled land. Hard rain, followed by scorching temperatures the next day hardened the soil surface, making it difficult for the shoots to pierce through. We tried to quickly run a plow through the land to help the seed, but the rain-heat cycle repeated the next day. That killed the seed …The heatwave just a few months prior had already destroyed almost half of my wheat crop, and then it rained heavily later in the season just when we were getting ready to harvest the mungi (mung beans) crop, killing it completely too.”

The dominant theme emerging from interviews and focus groups with farmers is “decision-making under uncertainty.” Almost as bad as the climate variability and change is not having complete (or enough) information about it. “Our most effective coping response is crop switching,” Zahid Joiya, an engineer-turned farmer from Sarhad, an agricultural town in Ghotki district in Sindh province, told me. “We do not have access to long-term climate data or even the capacity to analyze it to understand what may be happening with the climate. Nor do we have the capital to invest in conservation practices. All we can do is to use our best judgment and plant the crops that are less risky.” Less risky crops appear to mean either those whose exposure to the vicissitudes of the weather system is smaller—maize instead of wheat or cotton, for example—or the sturdy ones, such as sugarcane, which can withstand floods or moderately high temperatures. “This region used to be known for cotton,” Joiya continued, “but since the 2010 floods, almost everyone in our area switched to sugarcane. Cotton had become too risky, and we couldn’t keep up with increasingly dangerous pest attacks. On the contrary, sugarcane could withstand excessive heat and even torrential rains comparatively better.”

But in the past decade, as farmers switched en masse to less risky crops such as sugarcane, potatoes, rice, maize, and mung beans, prices crashed due to overproduction. Struggling to pay debts with their incomes falling below poverty line, many either gave up farming altogether or took out even more loans in the hopes of a bountiful crop in the next season or the one after that. Those with a bit of extra cash available have been trying exotic new crops in the hopes of making a profit. But as soon as the word spreads about a new crop that farmers can switch to, a glut follows, and the price crash bankrupts everyone. Crop switching has become a game of strategy. “In the last couple of years,” Joiya added, “it was a new high-yield variety of garlic which some thought could be sold at a good price. Overnight, it became so popular that most farmers were growing it only to sell as seed to other farmers. But the hype has died out, and now we’ve realized there is not enough demand for it in the country. Sugarcane has been good for us, but this year people are not happy with it. Nowadays, it is all about black wheat that some say can fetch a good price…. The trick is to get in on a fad early, make some money and get out before the bubble bursts.”

This haphazard crop switching and the resulting boom and bust cycles have added another layer of risk to an already precarious situation. Caught between overproduction and shortage, Pakistan’s domestic commodity markets have been struggling—exporting agricultural products one season only to import them back in the next. Although there hasn’t been a serious threat of food insecurity yet, the country has come dangerously close to it several times in the last couple of decades. Only last year, as the historic heatwave reduced the country’s wheat production by almost forty percent, the government hurriedly secured wheat imports to avoid food shortage in the country.

As for the farmers, the whole situation is confounding. Unable to fathom the complexity of the problem and armed only with a gut instinct and outdated agricultural practices, farmers find the situation unpromising.

Their struggle to adapt to the new normal is giving way to anxiety and frustration. Farmers, most of them small and medium landholders, are turning into a significant political force in the country. At least a dozen farmers’ representative organizations have sprung up across the country in the last ten years, demanding that the government “declare agricultural emergency, waive arrears of electricity and water bills (that many farmers have not been able to pay due to poor harvests or crop failures), subsidize agricultural inputs, and underwrite losses in the case of a price crash.” Thousands of farmers’ protests, rallies, demonstrations, and sit-ins have already taken place. More continue to be organized almost every day in cities big and small. The government keeps trying to pacify them by handing out billions of rupees in subsidies, but no amount of deficit spending can keep up with the violence that the shifts in the natural system have been imposing on farmers.

“The mood is somber in my village,” Shahbaz Ali said. “Markets are empty, as no one has any money to spend, and there are almost no weddings in this wedding season. Farmers have already planted crops for the next season, and after a frightful year of back-to-back crop failures, they are praying for an uneventful season ahead.”

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Pakistan, climate crisis, conflict and climate, extreme heat, extreme weather, farming, flooding, floods, food security

Topics: Climate Change