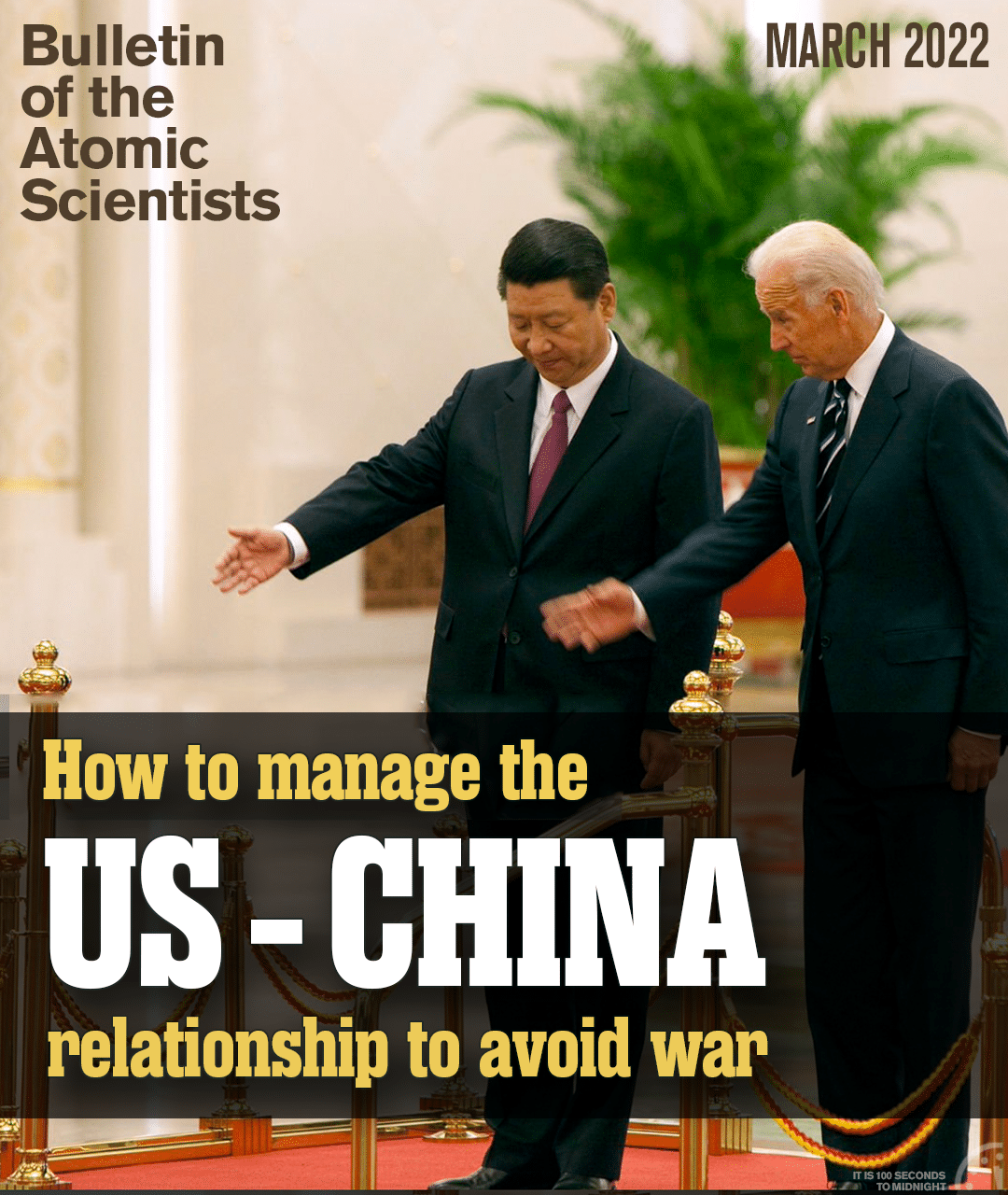

Interview with Graham Allison: Are the United States and China charging into Thucydides’s trap?

By John Mecklin, March 10, 2022

Warriors, side B from an Attic black-figure amphora, circa 570–565 BC. Courtesy Bibi Saint-Pol/Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain image

In his classic History of the Peloponnesian War, the Greek historian Thucydides wrote: “It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable.” In his critically acclaimed and best-selling 2017 book, Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap?, eminent international security analyst Graham Allison explores this phenomenon in modern eras when, as in ancient Greece, a rising power has threatened to displace a ruling one. The recent record is not particularly heartening: In the last 500 years, 12 of 16 such historical confrontations have ended in war.

Graham Allison has been a top analyst of national and international security policy for decades, advising or serving in the US Defense Department, State Department, and CIA and taking on a variety of leadership roles at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, where he has taught for more than 40 years. His Thucydides trap book has become a starting point for many—and perhaps most—serious discussions of recent US-China relations around the world. In this interview with Bulletin editor-in-chief John Mecklin, Allison explains why the United States and China appear to be falling into Thucydides’s trap and how the relationship between the world’s two greatest powers might be managed to avert war. (Editor’s note: This interview took place before Russia invaded Ukraine. It has been edited for clarity.)

John Mecklin: Your Thucydides’s trap article ran in The Atlantic back in 2015, followed by the book. And it’s almost seven years later. Are the United States and China falling into the trap?

Graham Allison: In short, yes. The book-length version—Destined for War, which was published just as Trump became president—forecasts that things will get worse, before they get worse. I’m often asked by folks in Washington, “Well, you know, that was five years ago. What would Thucydides say now?” And I answer that if Thucydides were watching, he would say: Both antagonists are right on script, almost as if they were competing to see which could better exemplify the characteristics of the rising power on the one hand, and the ruling power on the other. And that he’s sitting on the edge of his seat as they accelerate toward what could be the grandest collision of all times.

Mecklin: Given that happy view, what should the United States do to change its approach? I would understand if somebody had that sort of dark view with Donald Trump in the White House, saying all sorts of horrible things about China. What should Joe Biden be doing differently?

Allison: I am generally supportive of the president, whom I’ve known since the 1980s, and the team that he’s got wrestling with this, including [National Security Adviser] Jake Sullivan and [National Security Council coordinator for Indo-Pacific Affairs] Kurt Campbell, and [Secretary of State] Tony [Blinken], etc. But I think the objective conditions that Thucydides trap captures, and Thucydides described in his brilliant analysis of the rivalry between Athens and Sparta, create a dynamic that is extremely difficult to manage successfully. Indeed, as I’ve written elsewhere, I believe President Biden faces the most complex and extreme challenge any American president has had to try to cope with. In China, one confronts not only a meteoric rising power on all dimensions that has in a single generation become a full-scale peer competitor. We also confront a nation that has become the second backbone with the United States of the global economy—an indispensable economic partner of Germany, Japan, the UK, and most other major economies in the world.

Unlike the Cold War rivalry with the Soviet Union, where the Soviet Union essentially isolated itself from the global economy and traded only with the countries in its sphere, China has developed an economy that’s now as large as ours—indeed, by the yardstick CIA believes is the best metric for comparing national economies, an economy larger than ours. Hard to believe, yes; but go to the CIA website and look at their Factbook. China is the manufacturing workshop of the world. China is the most essential link in most critical global supply chains.

So let me step back, if I can. In trying to address this issue, one initially has to work on the diagnosis of the problem, to make sure that you have all the dimensions. In strategy, diagnosis precedes prescription [of a solution]. So the proper diagnosis, I believe, is to recognize this as a classic Thucydidean rivalry, in which a genuine, rapidly rising power is in fact, threatening a colossal ruling power.

As Thucydides explains, the Thucydidean dynamic is driven by three factors: material reality, psychology, and politics. At the material level, China really is rising and encroaching on positions and prerogatives Americans have come to believe are naturally ours. In the book I suggest we visualize this as a seesaw of power—with the United States on one end and China on the other. As China has bulked up, it is lifting our feet off the ground. Many Americans see this as an assault on who we are—since for us, USA means number one. Others are still “China deniers”—refusing to acknowledge that China could be number one in any race that matters.

Psychology combines perceptions and misperceptions with emotions and identity—often producing what Thucydides called “fear” in the ruling power and “arrogance” in the rising power. The rising power thinks, “Well, wait a minute; I’m just asking for my due. The current arrangements of the so-called order were put in place before I arrived. I now have grown, and I deserve more say—and more sway. That’s only reasonable.” And the ruling power’s perceptions and psychology begin with, “What the hell is going on here? Who does he think he is? What does he think he’s doing? Why is he not appreciative of the international order that we provided within which he was allowed to grow up?”

And then there’s a third layer of politics. Within the struggle for leadership within each government, a fundamental axiom declares: Never allow a significant political competitor to get to your right on a matter of national security. If he were looking for a poster child to illustrate this point, Thucydides could not find a better example than Washington today.

I have no doubt that some members of the Biden team get it. Certainly, Biden, Sullivan, and Kurt do. They appreciate that this is the best diagnosis of the challenge we face.

But if that’s the challenge, what about the response? I’ll confess that in Destined for War, I punt. The concluding chapters draw a dozen lessons from the earlier rivalries for escaping Thucydides’s trap. And the final chapter outlines four potential strategies that cover the spectrum from accommodation, on the one hand, to seeking to undermine the Chinese regime, on the other. But end with a rousing call for a surge of strategic imagination, as impressive as what occurred in the period between 1946 with the ‘Long Telegram” [on containment of the Soviet Union, written by George Kennan][1] and 1950 and NSC 68 and ultimately the framework for a Cold War strategy[2].

I’ve been working on this problem, and I still am short of an appropriate answer. But I’ll offer my current best idea: Because China is so much more complex a challenge than the Soviet Union, the fundamental problem is that we have to pass what F. Scott Fitzgerald of The Great Gatsby called the test of a first-class mind. Namely, we have to be able to hold two contradictory ideas in our head at the same time, and still function.

That’s a high bar. The two contradictory ideas and contradictory imperatives the Biden administration must respond to as it tries to find a way to manage this relationship are these: On the one hand, China is the most formidable rival any ruling power ever saw. So as [Singaporean statesman] Lee Kuan Yew said, China is becoming the biggest player in the history of the world. A nation with 1.4 billion people who are extremely talented and extremely ambitious believe their time has come. And China is displaying almost all the characteristics of a normal, rising power. In fact, and contrary to much of the Washington commentary, I believe the Xi government has not been excessively assertive, relative to rising powers at that stage in their own trajectory. I have a chapter in the book entitled “What if Xi’s China were just like us?” But not us as we imagined we are today, but as we were were when Teddy Roosevelt, at the beginning of the 20th century, was leading us into what he was supremely confident would be an American Century. And if you look at what we did, in what we call our hemisphere, relative to what Xi’s been doing at the same stage, he seems remarkably restrained.

In any case, one set of imperatives come from the fact that this rival—who has different values, and different views about how life should be organized, and how central to civil life individual liberties are—is a formidable competitor. On the other hand, both the United States and China live on a small planet in which technology and nature have condemned us to coexist—since the alternative is to co-destruct. China now has a nuclear arsenal that can absorb any American first strike and retaliate with a counterattack that destroys the United States as a functioning society. Thus, we have a condition that Cold War strategists identified as MAD: mutual assured destruction.

That’s a deep, deep, complicated, painful truth that those of us who lived through the Cold War came to internalize. Ronald Reagan captured the central truth in his favorite one liner: “A nuclear war cannot be won and must therefore never be fought.” This is a foundational insight. If I find myself in a nuclear war with you at the end of which my country has been erased from the map, who could call that victory? And if that’s true, I then have somehow to constrain my behavior and to persuade you to constrain your behavior that would lead us to confrontations, like the Cuban Missile Crisis, that could ultimately end in a war, a nuclear war.

So proposition one, we have a shared common interest in our own survival, and in avoiding the nuclear war, of which we would each be the first two victims.

We now have a second version of this that I’ve called climate MAD. We now understand in ways we didn’t earlier, that both the United States and China live in a small, contained biosphere in which greenhouse gas emissions from either of us goes into the same biosphere, and has the same impact on both of us. On our current trajectories, either of us, by itself, can so disrupt the climate, that neither of us can live appropriately within it. Unless the two of us can figure out a way to mutually constrain greenhouse gas emissions, we could make an unlivable biosphere. So that’s, again, a common shared interest that we are powerfully compelled to address for the sake of our own survival.

And I now think there’s a third dimension of this, which I’m still struggling to get my head around. If one considers the benefits of advancing global integration from creation of a bigger economic pie to advances in science, and technology, and medicine, and indeed, life as we know it, is it possible for a state to decouple itself from these benefits without impoverishing itself in a way that would be unsustainable for its political leadership? If the answer is no, then we have three dimensions of thick, inescapable interdependence that together condemn us to coexist.

The drive to survive is perhaps the most powerful motive for human beings. Thus, if my survival depends on finding some way to co-exist with you, however fierce our rivalry, I have to find a way. As Scott Fitzgerald pointed out, even for an individual, holding two genuinely contradictory ideas in your head at the same time and still functioning is really a stretch. To do that as a government and as a society, including our society today is even more so. So that’s the challenge that the Biden administration is wrestling with. So far, they’ve made some progress on the rivalry front, less on the necessities for cooperation. And beyond that, there’s the further issue of finding a way to articulate cooperation with China that would be politically palatable.

Mecklin: You’ve explained the setup to the situation very well. The United States seems to be in the process of constructing some kind of containment of China, something, with this pivot to Asia idea, involving new alliances and the moving of forces. I’m not sure that that exactly matches up to what you just described. Is a military surrounding, a containment strategy, workable, given the complex situation you just described?

Allison: That’s a good question and one that I’ve struggled with, too, so let me step back just one step, and then I’ll answer directly—since I think the answer is no.

Given the complexity of the competing imperatives that we just discussed, it’s not surprising that in trying to develop a playbook, people go back to historical analogs. The Cold War is becoming increasingly the preferred analog, even though most of the people talking about it don’t know what the Cold War was. They vaguely remember that somehow we won, so let’s do that again. It’s like the challenge you and the magazine have in trying to remind people that nuclear weapons didn’t disappear, either. In short, we live in the United States of Amnesia.

When people think about historical analogies, the Applied History Project here at Harvard recommends they follow the advice of Ernest May, one of the most distinguished international historians of the 20th century. According to what we call the “May Method,” when you think of an analogy, like the Cold War, put it at the top of the page. Draw a vertical line down the middle of the page and put “similar” at the top of one column and “different” at the top of the other column. If after reflection you can’t list three bullet points under each, take an aspirin and call a historian.

When I analyze the differences between the current situation and the Cold War with the Soviet Union, the differences outweigh the similarities. The first big difference is that China has an economy as big as ours, while the Soviet Union’s GDP never reached half that of ours. Secondly, China has established itself as the indispensable partner of most major economies including Germany, Japan, the UK, and 130 other nations. If we tried to build some new economic Iron Curtain, which side will we find them on? Germany’s major industry is automobiles and China is their No. 1 market. So as they and others keep telling American officials: Don’t try to get us to choose between our security relationship with you and our economic relationship with China, which is essential for our prosperity.

Now, what could people rightly have in mind? I think those in the administration who’ve though about this more strategically would say, “Well, what we’re doing with AUKUS[3] or with the Quad [4]or attempts to build positions of strength in Asia is to establish, at least in the military security area, a balance of power, or seesaw, where the correlation of forces advantages free societies like ours and our allies’ and partners’ over authoritarian competitors.”

Actually, I like that conceptualization since it recognizes that the China challenge is not a problem to be solved but rather a condition that will have to be managed. And if we are able to manage on a level playing field a long-term competition between democracy and autocracy, I’d sign up. I’m still enough of a traditional small “l” liberal committed to a society based on citizens’ liberties to believe that over the long run, that system will outperform a party-led autocracy. But we would see. Looking at the recent record, I understand why many Americans are disheartened. Looking at the recent record, the Chinese have some considerable grounds for their belief that their system—not just their society and economy, but their system—is in the ascendancy. But my bet is still on Team USA.

Mecklin: You’ve been talking about a rising power and a formerly dominant power, that relationship. But there’s a third power in here, Russia, that may not be playing economically, but certainly has the nuclear weapons and the guile to play some sort of role here, as it’s playing with Ukraine right now. How do you manage this really complicated, difficult US-China relationship when there’s a spoiler like Russia jumping up and down and saying, “No, look at me.”

Allison: Again, a great question. And in thinking about it, one’s reminded why it’s so much easier to offer advice from the sidelines than to be in the arena.

First, start with the historical canvas: We’ve seen many instances previously, in which there were not just the primary antagonists in a rivalry between a rising and a ruling country, but a third party as well. In the run up to World War I, it was not just Germany rising, threatening Britain’s predominance. Germany was also looking over its shoulder at Russia, which appeared to be getting its act together, building up its army and completing railroad lines for bringing troops to the German border to present a serious threat.

Second, as a result of the failures of American policy in dealing with post-Cold War Russia, on the one hand, and the brilliance of Xi’s diplomacy, on the other, we have essentially created what [Carter administration national security adviser] Zbig Brzezinski[5] called the “alliance of the aggrieved.” Two countries that should objectively find themselves at odds because of territorial disputes and history have quickly become thickly aligned.

Third, while most of the Washington policy community is trying to hold onto the mantra from the decade after the Cold War that declares “Russia doesn’t matter anymore,” the brute fact is that Putin’s Russia today is no longer the failing state many unilateralists remember. Putin’s Russia has a military that can fight and win to achieve political objectives. The Russians demonstrated this in brutally destroying Chechnya—which is now pacified under Russian rule. They demonstrated this in their attack on Georgia, which spiked its efforts to join NATO, and again in 2014 in seizing Crimea from Ukraine. In Syria, while Obama was declaring: “Assad must go,” Putin said “nyet.” And Russians smile when they remind American interlocutors that Obama is now gone, and Assad still rules Syria. If what one reads in the press and journals is an actual expression of what people really think, I’d say most of the Washington foreign policy establishment is not yet in this new reality zone.

In analyzing the current confrontation with Russia over Ukraine, consider five poker tables in which the hands have been dealt: the military cards, economic, diplomatic, hybrid warfare, and court of public opinion. I think Putin has the high cards in the first four of those games. The only arena in which we can seriously compete is the public sphere—and there I’d give the Biden team’s effort good marks.

On the global chessboard, the fact that in Xi and Putin—not just two countries but two leaders who each are planning on leading their country for a decade or even two decades ahead—have such a tight relationship makes the US challenge all that more complicated. But if we recognize the fact, it offers clues about the timing of any Russian invasion of Ukraine. To make the point, I’m prepared to offer you 4-1 odds that Russia does not invade Ukraine before February 20. That means I’ll bet $4 against your $1 on no invasion before that date. Why? Because the Beijing Olympics that begin on Feb 4 run to Feb 20th; Xi has designed what he’s promised will be a “spectacular” show that shines the spotlight on a China that now stands tall; the most honored foreign guest at this event will be Vladimir Putin; and there is no way that he will rain on Xi’s parade.

Mecklin: Interesting that something like the Olympics could have that power.

Allison: Yes. And a good reminder that these leaders of countries are fellow human beings. Relationships among them really matter. Watch the body language. Remember: Putin calls Xi his “best buddy.” While China has only recently been active in most of the winter sports and thus is not going to win many medals, I have no doubt that the opening and closing ceremonies are going to be off the charts.

Mecklin: It’s going to be interesting to see them try to do that, in the middle of a pandemic, when exactly nobody goes there. We’ll see; maybe they’ll pipe the applause in. I wanted to ask about two other things. One is this: You’ve been talking about a very complicated and difficult management situation for the United States versus a rising China. Within that difficult situation, how does the United States continue to push for human rights and democracy? I mean, what’s happening to the Uyghurs is horrible.

Allison: Great question. Jake [Sullivan] has given the best answer to it that I’ve heard recently. First and foremost, this is about who we are. Start with the old Cold War mantra. Our overriding objective is to ensure the survival of the United States as a free nation, with our fundamental values and institutions intact. So the purpose of the United States in the world is first to provide space for a society to realize what free people can do. The centerpiece of our values is liberty for individuals. And that’s the core of America’s commitment to human rights: first survival, and then the Bill of Rights, and then what ultimately becomes the UN Declaration of Human Rights.

The thought that it’s possible to create a government and a society in which individuals can be free to the maximum extent to realize their potential—is a radical idea. But it is the core of the American experiment. We don’t always succeed but that’s what we aspire to be—and what we encourage in other countries. As we re-learned in Afghanistan, attempting to promote democracy through the barrel of a gun is misguided. But affirming our values, standing up for them, calling out abuses of fellow human beings wherever they live, reflects our identity. And in the long-term competition with China, we are confident that a freedom-based democracy will prove superior to a Party-led autocracy in delivering what people want.

Of course, foreign policy pursues multiple objectives and hard cases require tradeoffs. So it’s complicated. But in contrast to realists who dismiss or denigrate human rights, or some activists who imagine that the promotion of human rights should be the only objective, my view is that the centerpiece of American engagement in the world is to build a world safe for free human beings to be all they can be—beginning here in the USA.

Mecklin: Last thing I wanted to ask you about is something that may or may not be fun for you. I’m going to throw an old proposal of yours back at you—for a White House Council of Historical Advisers.

Allison: Yes, I’m still an enthusiast.

Mecklin: Why? Tell people why that would be a good idea.

Allison: Why do we have a Council of Economic Advisers? The answer is because we believe that by analyzing some of the choices that the president and the government have to make, professional economists can clarify the choices and their likely consequences. How well do they do? Well, excuse me, look at the inflation we have today. Did they forecast that? Nope. They don’t have a crystal ball. The real world is highly uncertain. Nonetheless, relative to people who know no economics, they do a little bit better most of the time. Not as well as they claim—but a little bit better.

My colleague Niall Ferguson and I proposed an analog that could be called the Council of Historical Advisers. They would not have a crystal ball that would allow them to predict what’s going to happen in the confrontation with China or Russia. But by analyzing the historical record, and by being systematic about historical analogies that policy makers grab in trying to make sense of a confusing world, like Cold War or containment, they can help illuminate the challenges that we face and the choices. I’m happy to report that the Applied History movement now includes not just Harvard and Stanford, but vibrant work at the Kissinger Center at Johns Hopkins, the Clements Center at the University of Texas at Austin, at Duke, Ohio State, Berkeley and a dozen other universities that actively have people doing this.

If the question were, “What the hell is going on in the current confrontation with Putin, and why might he be doing this now?”, that would be a good question to give to the Council. And you can see the pontification about it in a many, many publications, who knows maybe even your own.

Mecklin: A little bit, yeah.

Allison: To be suggestive, let me mention one of the tools in the Applied History toolbox. It begins with the recognition that for many policy makers and most of the foreign policy community, in what’s been called the United States of Amnesia, every day is a new day where we begin with a clean whiteboard. Thus, the current confrontation with Putin is like a frame or snapshot from the course of a movie. But the applied historians remind us that what we see today is just the most recent frame in a process that has evolved over the past year or even decade. So the applied historian asks: “Show me the main scenes in the movie that led to the current picture. Or how about give me the main events in the movie that led to the current picture?” That sequence goes back at least to 2014 when Putin seized Crimea. Analyzing that event, what were the underlying factors, what were the proximate causes? The historian would note that this came after the color revolutions that overthrew governments in Georgia and Ukraine; that the EU was in a bidding war with Russia over Ukraine; that the Yanukovych government which the US certified had been legitimately elected was overthrown by the Maidan demonstrations; that the new government had Ukraine on a fast slide towards the EU. All this presented Putin the specter of the Russian navy’s major warm water port in Sebastopol, which had been built by Catherine the Great, falling under the control of NATO—an outcome no Russian would accept if there were any alternative. And to understand that, the historian would go back to scenes from 2008 when at the NATO Summit in Bucharest the Bush administration, and [Secretary of State] Condi [Rice] pushed for an entry into NATO of Georgia and Ukraine.

In trying to answer the question of why Putin is acting now, in 2022, an applied history analysis would review key scenes over the past two years: actions by Ukraine, Europeans, and the US as well as those by Russia or others. Answering that question would require overcoming the myopia that dominates most thinking in Washington—what HR McMaster called “strategic narcissism.” The alternative is to develop a capacity for “strategic empathy” in which one tries to get inside the adversaries’ skin, to see the world through his eyes, and to think about his interests and threats to him as he does. The goal is not to legitimize or sympathize with his values and views, which can frequently be deplorable. Rather, it is to do a better job of forecasting what his next step might be, and to be in a better position to try to influence his behavior.

So I think, bottom line for the Council of Applied Historians: If the benchmark is the assistance that the Council of Economic Advisers provides in helping to clarify the economic dimensions of economic issues, historians could help clarify the geopolitical history and the factors that lead to the challenges and choices that the president faces today.

ENDNOTES

[1] George Kennan’s February 22, 1946 ‘Long Telegram’ can be found at the Wilson Center archives at https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/116178.pdf

[2] NSC 68, also known as “A Report to the National Security Council – NSC 68,” April 12, 1950, can be found at the Harry S. Truman Library archives at https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/library/research-files/report-national-security-council-nsc-68?documentid=NA&pagenumber=1

[3]The Joint Leaders Statement on AUKUS, September 15, 2021, can be found at the White House Briefing Room site at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/09/15/joint-leaders-statement-on-aukus/

[4] For more information, see Sheila Smith’s May 27, 2021 article for the Council on Foreign Relations titled “The Quad in the Indo-Pacific:What to Know” at https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/quad-indo-pacific-what-know

[5] For more, see the May 26, 2017 New York Times article “Zbigniew Brzezinski, National Security Adviser to Jimmy Carter, Dies at 89” at https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/26/us/zbigniew-brzezinski-dead-national-security-adviser-to-carter.html

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: China, Cold War, Russia, Thucydides's trap, Ukraine, containment, human rights

Topics: Interviews, Opinion, Special Topics

“… overcoming the myopia that dominates most thinking in Washington—what HR McMaster called ‘strategic narcissism.’ “

Too much time spent determining angels on a pin.