Comics, graphic novels, and the nuclear age

By Ariane Tabatabai | October 26, 2015

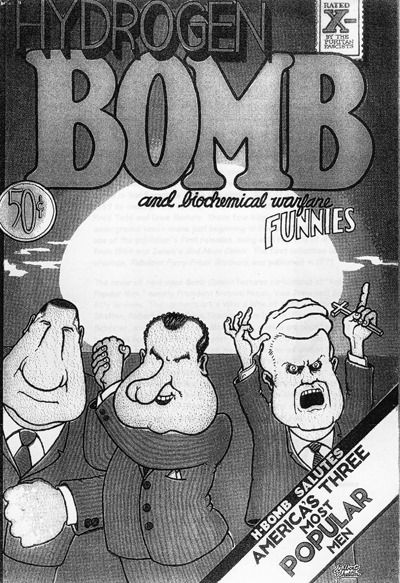

Nuclear weapons have long captured the imagination of writers and filmmakers as a symbol of humanity’s incredible yet terrifying potential, of its intelligence, hubris, and vulnerability. Much like other technological inventions, such as robots, nuclear weapons allow pop culture to explore the limits of human control over human creations. The general public might not always view comic books and graphic novels as a serious medium, yet they offer a fascinating perspective on the nuclear age.

Like pop culture more generally, comic books and graphic novels began to explore the nuclear issue during the Cold War, a time when nuclear war didn’t seem like a scenario out of an action flick. Fallout shelters and Bert the Turtle (who taught children to “Duck and Cover” in the event of a nuclear attack) constantly reminded Americans that a nuclear strike could occur at a moment, sometimes even making it seem inevitable. The threat was also felt in other countries, and eventually pop culture began to capture the unease.

Raymond Briggs’ disturbing When the Wind Blows (1982) reflects this anxiety. Set in the United Kingdom, the novel follows an elderly rural couple surviving a nuclear attack. The story’s power stems from its ability to humanize the consequences of nuclear weapons. It doesn’t describe a blast killing thousands in an instant. Instead, it takes readers through the entire story, from the couple learning about the possibility of an attack and getting ready to live through it, to the pain and suffering that follows it. The book’s graphics and dialogue, its amusing and optimistic tone, stand in stark contrast with the sadness and pessimism of the story itself. Briggs’ message is clear: It doesn’t matter if you follow the “Protect and Survive” leaflet (the UK version of “Duck and Cover”); humanity has set in motion its own destruction.

Such destruction is also a theme of the influential Watchmen series (1986–87). Created by Alan Moore, Dave Gibbons, and John Higgins, Watchmen plays off the superhero genre so central to comics and graphic novels, but immerses it in an alternative Cold War history. The story takes place in 1985, as the United States and the Soviet Union escalate toward nuclear war. The US has strategic advantage over the Soviets thanks to the aptly named Doctor Manhattan, a character based on the 1960s superhero Captain Atom. Once a nuclear physicist named Jon Osterman, he turned superhero in the late 1950s, when a laboratory accident transformed him into a powerful, superintelligent, radiated being. He’s therefore the only true superhero (by virtue of possessing superpowers) among the Watchmen, a group of costumed vigilantes who once reshaped history by giving the US an edge in foreign policy only to become unpopular with the public and suspicious to authorities. He is also owned by the US government. As such, Doctor Manhattan epitomizes the philosophical questions of the nuclear age, including those that deal with the ethics of deterrence and humanity’s relationship with technology. After his accident, Doctor Manhattan begins to lose his ability to relate to other humans, distancing himself from his vigilante friends and lovers alike. This mutation from normal man to technological marvel, a deterrent packaged in human form, allows the authors to explore questions surrounding our relationship with technology and security.

Since the end of the Cold War, authors have continued to address nuclear issues, but have generally done so by exploring its nuclear history and discussing real-world nuclear challenges. Indeed, before the 1990s, most comics and graphic novels dealt with nuclear weapons as “mystical” forces. But in recent years, many of the graphic novels tackling the subject have been non-fiction. This is perhaps because the general public no longer views nuclear war as a real and imminent threat.

For example, two graphic novels take on the Manhattan Project. In Fallout (2001), Janine Johnston, Jim Ottaviani, Jeffrey Jones, and Chris Kemple take a stab at explaining the science behind the project, as well as its political, ethical, and military dimensions. Although some might dismiss it because it is a graphic novel, Fallout (subtitle: J. Robert Oppenheimer, Leo Szilard, and the Political Science of the Atomic Bomb) is actually a great overview of one of the most decisive and complex projects in human history, partly thanks to Ottaviani’s nuclear engineering background. Jonathan Fetter-Vorm’s Trinity: A Graphic History of the First Atomic Bomb (2012) tackles the same challenge as Fallout: Explaining a project so rich and complex, crisscrossed by history and politics, military and security questions, and science and ethics. The book reaches its apotheosis in the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Unsurprisingly, these bombings have also been the subject of countless of manga comics in Japan, especially two series by Nakazawa Keiji, Struck by Black Rain (1966) and Barefoot Gen (1973–85). Struck by Black Rain discusses the effects of the bombing in Hiroshima by following a group of young survivors who become involved in a weapons black market. The protagonist takes revenge by killing an American. Barefoot Gen is more closely based on the author’s own life. It tells the story of a small, poor boy who survives with his mother, who gives birth to a daughter, while the rest of the family die in the bombing. While American and European authors often convey anxiety when discussing nuclear weapons as a result of their Cold War experiences, prevalent themes in Japanese books discussing nuclear weapons are often anger, resistance, and struggle.

Leave it to the French, though, to create a graphic novel about nuclear diplomacy. It began with the Franco-Belgian comic tradition of BDs (in literal translation, “drawn strips”), a tradition serious enough that President François Hollande once opened the doors of the Élysée Palace to the graphic novelist Mathieu Sapin to write about the executive residence and its occupant. In many countries it might seem weird for a foreign minister’s old speechwriter to write a graphic novel about diplomacy in the months leading to war, but France is not one of them. Hence Antonin Baudry’s Weapons of Mass Diplomacy (2012), a funny and insightful look at the French Foreign Ministry in the months leading to the Iraq War. Writing under the pseudonym Abel Lanzac, Baudry depicts a charismatic foreign minister (Dominique de Villepin in real life, Alexandre Taillard de Vorms in the book) who decides to challenge the United States. His semi-dysfunctional team frantically tries to stay on top of events while the clamor for war drowns out the voices of nuclear experts. The book, along with the 2013 film based on it, are an entertaining yet powerful explanation of one of the most influential foreign policy decisions in recent years.

Seventy years have passed since the world entered into the nuclear age, and nuclear weapons continue to be a source of inspiration in pop culture. They have allowed authors to reflect on humanity and raise important ethical and philosophical questions. Comic books and graphic novels provide an interesting and unique platform that allows authors to push barriers and tackle difficult topics. Art Spiegelman’s monumental graphic novel Maus (1991), which recounts his family’s life during the Holocaust, and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis (2000), which depicts her life as a little girl in revolution-era Iran, are a testament to their potential. Indeed, comics and graphic novels have provided a means of deep and nuanced thinking about nuclear weapons for decades, raising questions and offering perspectives many readers might still not expect from such a colorful medium.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Columnists, Nuclear Weapons