Floating nuclear power plants: China is far from first

By Dawn Stover | June 1, 2016

On April 22, the state-owned Chinese newspaper Global Times reported that China plans to build as many as 20 floating nuclear power plants, the first of which could be producing power in just a few years. The story made a splash because the power from the floating reactors would most likely be used to accelerate construction of oil rigs and artificial islands in the South China Sea—already a source of border disputes and escalating tension between China and its neighbors.

Portable power stations may sound futuristic, but the idea is far from new. The United States launched the first floating nuclear power plant five decades ago, and Russia started its own construction project in 2000. Where the United States has seen a proprietary technology, though, China sees a marketing opportunity.

China floats an idea. Earlier this year, as part of its latest five-year plan, China’s National Development and Reform Commission approved the development of two nuclear reactors for marine platforms, one each from the country’s two big nuclear companies: The China General Nuclear Power Group will develop the ACPR50S, a small modular reactor with a generating capacity of 200 megawatts. Meanwhile, the China National Nuclear Corporation plans to work on the AC100S reactor, a marine version of its ACP100, which would generate 100 megawatts.

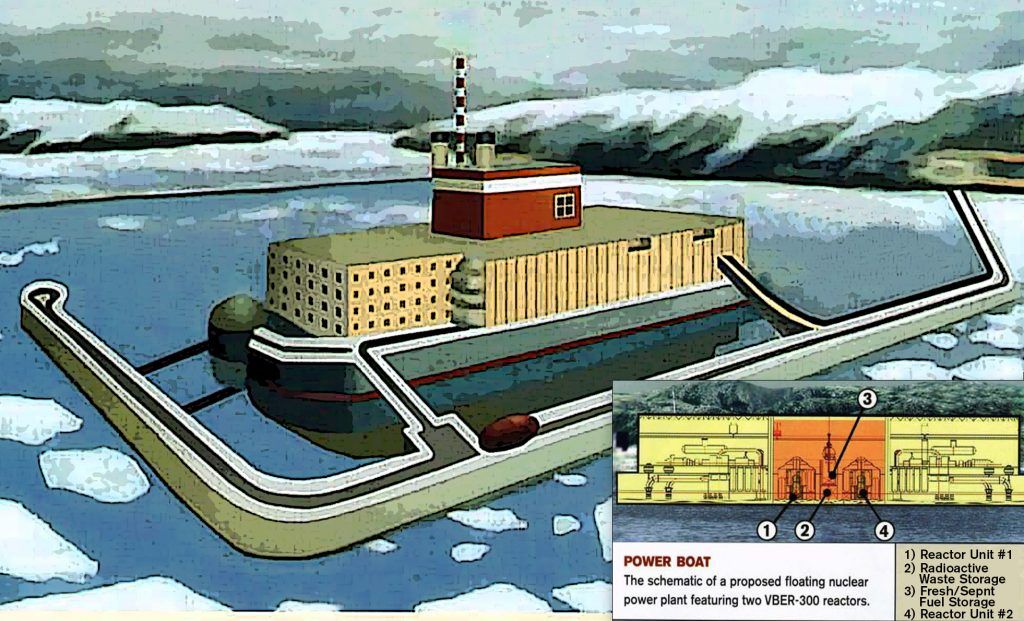

China General Nuclear has signed an agreement with China National Offshore Oil Corporation, which would presumably use floating nuclear power plants to provide power for offshore oil and gas exploration. China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation, the country’s largest shipbuilder, is building a barge-like platform for China General Nuclear’s pilot plant. An illustration of the platform looks very similar to Russian designs, which is not surprising. Only a few years ago, the Chinese were planning to build floating nuclear power plants in China using Russian technology; now the Chinese are floating their own designs.

Besides providing power for drilling platforms, Chinese floating nuclear power plants would also be used to construct and operate artificial islands that China is building atop reefs, in its attempt to secure claim to a vast area of the South China Sea. The remote islands currently rely on power from fuel-thirsty generators.

Fossil fuel extraction and maritime conquest aren’t the only potential uses for floating nuclear power plants, however. They could eventually be used as power sources for island nations, remote coastal areas, desalination plants, and perhaps even coastal cities where energy demands are soaring. The head of China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation’s general office, Liu Zhengguo, told the Global Times, “The development of nuclear power platforms is a burgeoning trend” and said that demand is “pretty strong.”

The American trailblazer. Nuclear reactors have already been used to power oceangoing vessels, of course, beginning with the USS Nautilus submarine in 1955. According to the World Nuclear Association, there are now more than 140 nuclear-powered ships in the world, including icebreakers and aircraft carriers as well as subs.

The United States was the first country to build a floating nuclear power plant, the USS Sturgis, which was launched in 1943 as a Navy transport ship but was repurposed in the 1960s with the installation of a 10-megawatt nuclear reactor in its hull. Dubbed the MH-1A (short for mobile, high power, first of its kind), the power plant was towed to the Panama Canal Zone in 1967, and until 1975 provided electricity for pumps that operated the locks. By that time, it required too much maintenance—and highly skilled technicians. It is currently being dismantled in Galveston, Texas.

Only a few years after the MH-1Abegan operating in Panama, a company called Offshore Power Systems proposed mooring a floating nuclear power plant to a man-made island off the coast of New Jersey’s Atlantic City. The project raised safety and environmental concerns, though, and was dead in the water by 1978.

The Russian effort. In the past 25 years, Russia has revived the idea of floating nuclear power plants. As the Bulletin reported in the summer of 2006, the Sevmash Shipyard in Severodvinsk was hoping to complete construction of a nuclear power plant mounted on a barge by the end of that year, using a modified reactor from a Russian icebreaker. The report noted: “The floating reactor has been an on-again, off-again project since the early 1990s when Russia began promoting it as a cheap way to power the country’s Arctic regions.”

Within a few years, the program was off-again at Sevmash, but it is now on-again at a shipyard in St. Petersburg, where the first two Russian floating nuclear power plants are being built. The first, the Akademik Lomonosov, is equipped with two 35-megawatt KLT-40S reactors, and will be towed to the Arctic port of Pevek, where it will generate both heat and electricity. Fuel loading is scheduled to begin in December, with delivery to Pevek to follow in 2018 or 2019. The second plant is planned for Vilyuchinsk, a town on the Kamchatka Peninsula, but completion of both plants has been repeatedly delayed.

Potential risks and rewards. Russia’s nuclear-powered icebreakers use highly enriched uranium, but the modified reactors for the Akademik Lomonosov will run on low-enriched uranium. That helps to alleviate concerns about proliferation, but environmental and safety concerns remain. A floating nuclear power plant would probably be safe from earthquakes, but storms could be a threat, and accident response would be slow in remote Arctic areas.

In the event of a nuclear accident, an offshore plant would have plenty of cooling water readily available. But a floating nuclear power plant might not have access to off-site backup power, and it would be more difficult to contain any radioactive releases than when an accident occurs at a land-based plant. A failed reactor might end up being abandoned at sea, as has happened to seven Soviet or Russian nuclear submarines.

Those risks aren’t preventing the Russians and Chinese from moving ahead with plans for floating nuclear power plants. Russia hopes to lease floating plants to other countries, and China sees an opportunity to capitalize on technologies originally developed by the United States and Russia.

While floating power plants may seem to present exciting economic opportunities–both for sites lacking affordable power and for the entities selling the plants—they also come with major risks. As Bennett Ramberg, author of the book Nuclear Power Plants as Weapons for the Enemy: An Unrecognized Military Peril, noted in the Bulletin’s March 1986 issue: “[F]acilities can be placed on large lakes, inland seas, or oceans—on floating platforms surrounded by breakwaters, on floating vessels anchored to the marine floor, on artificial islands, or even undersea. However, there would be higher transmission costs for reactors, unique construction costs, and exposure to such dangers as ship collisions, accidental explosions, and naval bombardment.”

Thirty years later, “naval bombardment” is a growing risk in the South China Sea. A floating nuclear power plant might make a tempting target.

Editor’s note: The Bulletin’s archives from 1945 to 1998, complete with the original covers and artwork, can be found here. Anything after 1998 can be found via the search engine on the Bulletin’s home page.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Analysis, Nuclear Energy