OPLAN 2045: Preparing for nuclear disarmament

By James E. Doyle | November 28, 2016

Seven years after President Obama pledged to work toward a world without nuclear weapons and 25 years since the end of the political and ideological conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union known as the Cold War, the world is witnessing renewed nuclear arms competition. In Asia, China, India, North Korea, Pakistan, and possibly Israel are expanding and diversifying their nuclear forces. In Europe, Russia has made nuclear weapons modernization a central element of its military strategy and is taking reckless actions with potentially nuclear-armed aircraft and making irresponsible statements about possible nuclear weapons use. The United States, meanwhile, has embarked on a nuclear modernization program covering the full range of its forces, at a cost that will far exceed the nuclear build-up under President Ronald Reagan.

The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) clearly is under strain. The final documents from the 2000 and 2010 NPT review conferences affirmed the treaty's requirement that nuclear-weapon states disarm. But instead of fulfilling these obligations, those five signatories apparently see nuclear weapons as an enduring aspect of national and international security. The 2015 NPT review conference ended without consensus on what actions to take toward the goal of nuclear disarmament in the years ahead. Motivated by the more than 45 years of inaction towards real nuclear disarmament, the First Committee of the UN General Assembly on October 27 adopted a resolution to convene negotiations in 2017 on a “legally binding instrument to prohibit nuclear weapons, leading towards their total elimination.” The voting result was 123 nations in favor and 38 against, with 16 abstentions.

With the nuclear-weapon states and their allies headed away from the increased security a world without nuclear weapons would bring, it is time for the world’s citizens and non-governmental organizations to play a leading role in creating the architecture of our future security environment. We must act now to create a multilateral plan for verifiable nuclear disarmament by the year 2045, 100 years after the first use of nuclear weapons. No government has attempted this, despite accepting legal and political obligations to do so.

Given that many governments seem unwilling to plan disarmament in the current environment, one way to get started would be for a consortium of non-governmental organizations and like-minded governments to undertake such planning, in an initiative that might be called “OPLAN 2045.” Once a detailed but flexible long-term operational plan is established, those supporting it could push for its inclusion in five-year NPT review conferences, with the goal of making detailed consideration of progress toward disarmament a regular part of the NPT process. In other words, monitoring progress on OPLAN 2045 could be integrated with the 2010 NPT Action Plan and proceed in parallel with negotiations in the UN First Committee to ban nuclear weapons.

How would operational planning help? In basic terms, operational planning is the process of linking strategic goals and objectives to tactical goals and objectives. An operational plan describes milestones and conditions for success and explains how portions of a strategic plan will be put into operation during a given period. The term “operational plan” as related to nuclear war entered the popular lexicon after revelations regarding the Single Integrated Operational Plan or “SIOP” appeared in the news media, books, and films. SIOP-62 was the United States' general plan for nuclear war from 1961 to 2003.

It is appropriate to borrow the “operational plan” (OPLAN) nomenclature for a program to eliminate nuclear weapons. The practical parallels between planning for nuclear war and planning for the elimination of nuclear weapons are many; they include high complexity, a universal set of stakeholders, multiple technical and political challenges in several domains, and a vast number of organizations and individuals that must act in a coordinated manner to achieve objectives.

There are also, of course, dissimilarities, chiefly in terms of the time scale. The execution of a nuclear war plan would occupy minutes, hours, days, or perhaps a week before either ceasing after a handful of detonations or continuing as an exchange of hundreds, if not thousands of weapons. By contrast, a plan to eliminate nuclear weapons from national arsenals will take decades to implement.

But the 30 years leading up to 2045 would constitute a period of reasonable length for dramatic, substantial progress toward achieving a longstanding but elusive international goal. Of course, if more rapid progress became politically and technically feasible the target date could be moved up.

The need for a plan. Creation of a draft integrated operational plan for the multinational elimination of nuclear weapons would have many benefits, even if the plan had no official governmental commitment to implement it when it was created. Establishing such a plan provides an organizing principle for cooperative efforts, a baseline concept that organizations and individuals can comment on and refine, multiplying their effectiveness. This type of plan can also provide a means of gauging states’ degree of commitment to the goal of nuclear weapons elimination; it would identify states that act as primary roadblocks to achievement of strategic objectives and those that facilitate progress. An operational plan outlines specific actions that need to be taken within a defined time frame and provides a preliminary definition of roles and responsibilities among actors. It can help coordinate the efforts of disparate actors by providing a shared roadmap. This can help develop a realistic understanding of the sequencing of events, help avoid duplication of effort, and keep action focused on obstacles along the critical path to the objective.

An operational plan would also provide a means of strengthening the credibility of international commitments to nuclear disarmament. Eliminating nuclear weapons from national arsenals will require the collective efforts of millions of individuals and hundreds of governments, multinational institutions, and non-governmental organizations. If significant elements of the international community do not believe that leading states and organizations are genuinely committed to the strategic objective, they will be reluctant to contribute their effort and resources. They will remain on the fence, hedging against the possibility that no significant steps toward nuclear disarmament will be taken.

Even more destructive to the long-term goal of nuclear disarmament is the possibility that, without a concrete plan and evidence of progress, key players will distrust the intentions of leading states and organizations claiming to embrace disarmament. They might conclude that such claims are a ruse through which nuclear-armed states seek to maintain their advantage, while increasing the political cost to any new states of acquiring nuclear arms. Coalitions of countries have made this charge—that the nuclear weapon states have paid only lip service to their commitment to eliminate nuclear weapons—frequently over the years. Deep skepticism about the intentions of the nuclear weapons states is providing impetus for a treaty that would declare development and possession of nuclear weapons illegal.

Third, an operational plan would enable practitioners and activists to identify the most direct route to nuclear disarmament and the key obstacles standing in the way. A sophisticated plan would permit users to explore alternative tactical pathways to overcome or bypass each obstacle. It could enable the NGO community to draw attention to the most immediate obstacles and those responsible for delaying progress. It could also facilitate creative thinking about new routes toward achieving strategic milestones. And OPLAN 2045 could enable analysts and activists to recognize when planned routes toward strategic goals were simply too difficult to pursue, stimulating new ideas that could be injected into the debate on how best to eliminate the risks of nuclear war until new paths to nuclear disarmament could be found.

Finally, an operational plan for nuclear disarmament would provide a vehicle for periodically measuring progress or backsliding. The NGO community could utilize this vehicle for bringing public pressure to bear on the countries that are blocking progress and for rewarding those facilitating it. In this way progress on OPLAN 2045 could serve as a bellwether for the time when humanity might eliminate the threat of nuclear annihilation. A converse of the “doomsday clock” featured in this publication could be set by the degree of progress being made by OPLAN 2045. Instead of “fifteen minutes to midnight,” a new clock could be set at 30 minutes to a world free of nuclear weapons and move forward as progress is made.

The flexible structure of a plan. OPLAN 2045 could originate in and draw upon dozens of previous and ongoing plans for achieving progress toward nuclear weapons elimination. It should be a long-term, operational plan designed and implemented collectively by the international community. Whenever it is practical, multiple pathways should be identified to reach critical milestones on the path to nuclear disarmament.

OPLAN 2045 can identify essential steps and activities that various entities need to accomplish within a general time frame, but it should be flexible and adaptive. For example, the OPLAN need not necessarily conform to a specific timeline. When possible, resources and mechanisms needed to achieve various steps should be identified. However, the ability of OPLAN 2045 to provide such proscriptive detail is limited, because social and political realities are constantly evolving. As conditions change, so do the structures of opportunity or entrapment.

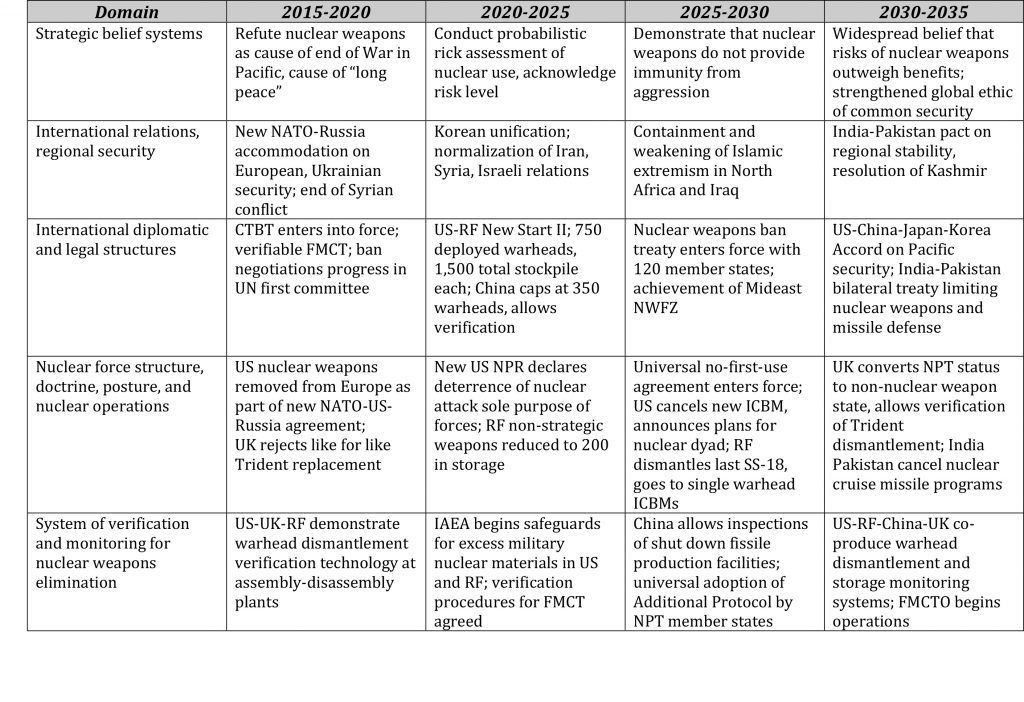

One possible structure for OPLAN 2045 would define the necessary conditions for achieving nuclear disarmament across five widely accepted domains of statecraft and strategy, over three 10-year periods. The domains are interrelated but not rank-ordered.

The first such domain involves strategic belief systems related to nuclear weapons and the evolution of such belief systems over time. Currently, the belief that nuclear weapons play a positive role for states possessing them (and also for the larger international system) remains strong. Several governments still view nuclear weapons as the ultimate insurance policy and believe their possession of nuclear weapons boosts influence and prestige, domestically and internationally. Strong political elites believe that nuclear weapons have prevented direct conflict between nuclear-armed powers and that they increase the likelihood of caution and rationality among leaders in a crisis and therefore tend to have a stabilizing influence in international affairs.

An opposing belief system holds that nuclear deterrence, a concept under which nations threaten to destroy cities in the name of self-defense, is immoral and unjustifiable, and that nuclear weapons, like other weapons of mass destruction, are illegitimate means of warfare. This group believes that the existential risk of nuclear use by accident or miscalculation is unacceptably high, and that the use of nuclear weapons would cause indiscriminate widespread harm to civilians and their environment and would therefore constitute a crime against humanity. This belief system asserts that all states have accepted obligations to make real progress towards the elimination of nuclear weapons and that nuclear weapons and nuclear deterrence are ineffective for today’s most likely threats, such as terrorism and climate change. Finally, this group believes nuclear deterrence is, like slavery, an institution that can be abolished or made taboo, and nuclear weapons can be legally banned, as were chemical and biological weapons.

OPLAN 2045 should consider significant trends in this domain over time and identify changes in belief systems that would be necessary, helpful, and detrimental to achieving the elimination of nuclear weapons. Actions that can support the strengthening of positive developments in this domain are a vital part of OPLAN 2045.

The second domain, international relations, would include strategies for the stable transformation of the international system, for the resolution of conflicts within specific regions, and for the development of improved regional security structures. This domain would cover both political and economic relationships. Efforts to maintain strategic stability between major powers, increase global interdependence, and improve the effectiveness of international organizations also would occupy this domain. OPLAN 2045 would identify areas of common interest among states and provide examples of how cooperative security approaches could address mutual threats and reduce mistrust, reducing motivations for nuclear weapons acquisition. The challenge of conventional military imbalances that hinder the elimination of nuclear weapons must also be addressed in this domain.

Because regional tensions in South Asia, the Middle East, and East Asia have persistently been identified as motivating nuclear weapons development, reducing those tensions should be a focus of OPLAN 2045. This will require addressing longstanding political and territorial disputes, tensions resulting from shifts in relative power and influence among states, and continued domestic instability and military extremism within some states. Achieving progress will likely require decades of sustained effort and the creation of new regional security structures.

A third domain, international diplomatic and legal structures, includes a variety of bodies and laws that seek to reduce nuclear security threats, including those of nuclear war, nuclear terrorism, and nuclear proliferation. First and foremost in this domain are the NPT and such other elements of the nonproliferation regime as formal bilateral or multilateral nuclear arms reductions treaties, strategic trade controls, multilateral initiatives to combat nuclear terrorism, nuclear weapons-free zones, and nuclear confidence-building measures. It also includes the legal authorities and decisions of the United Nations and the International Court of Justice.

OPLAN 2045 should outline specific steps to “legal zero,” with respect to using international law to prohibit the manufacture, possession, or use of nuclear weapons. Decades of work have already gone into such efforts. Several key agreements, including the Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) and Fissile Material Cut-Off Treaty (FMCT), could be brought into force in the relatively near future. Such outcomes would provide significant momentum to the quest for nuclear disarmament. It is unclear what combination of legal mechanisms will be required to ultimately eliminate nuclear weapons from national arsenals, but new multilateral instruments, possibly including the proposed “ban” treaty to be negotiated in the UN first committee beginning in 2017, will certainly be needed. An essential part of this domain will be the creation of international organizations with the authority and capability to enforce a future convention banning nuclear weapons.

The fourth domain consists of nuclear force structures, doctrines, postures, and operations. This domain is fairly straightforward in its definition. There is clearly overlap with the domain of strategic belief systems, because of the link between deterrence theory and nuclear weapons doctrine. The development and deployment of nuclear weapon systems fall within this domain, as do the characteristics of existing nuclear arsenals.

OPLAN 2045 should address this domain with suggestions for changes in declared nuclear doctrine, degrees of transparency in doctrine, force structure, acquisition, and weapons-reduction plans. Additional subjects in this domain include: short-range or “tactical” nuclear arms; the relationship between missile defense and nuclear strategy; and the relationships between non-nuclear strategic forces (e.g. conventional global strike), cyber security and nuclear weapons.

The fifth domain of OPLAN 2045 would deal with verification and monitoring of nuclear weapon elimination and safeguards on civil nuclear facilities, so they could not be quickly converted to produce weapon-grade fissile material. This domain encompasses the diplomatic, technical, and procedural mechanisms that would provide confidence to the international community that states are fulfilling their nuclear disarmament obligations. There are two key interrelated challenges in this domain. The first is the political challenge of negotiating treaty provisions and establishing a treaty implementing organization that has the authority and capability to use verification systems and resolve technical issues and related disputes. The second is to demonstrate verification technology and inspection protocols that can assure compliance with treaty obligations without revealing information that harms the national security of the treaty partners or reveals nuclear weapons design information to potential proliferators.

Obviously, this domain is directly related to international diplomatic and legal structures. Historically, most nuclear arms reduction agreements were negotiated and implemented bilaterally, between the United States and the Soviet Union, and more recently with Russia. Negotiating and verifying multilateral nuclear arms reductions that eventually encompass all states will be more challenging and complex in some ways but may offer advantages as well. Also, some states may prefer to eliminate their nuclear arsenals unilaterally and then allow verification by an international organization, as in the case of South Africa. In either case, much could be done to prepare for new arms reduction efforts by jointly developing inspection technologies and conducting joint verification experiments that involve nuclear weapon states, non-nuclear weapon states, NGOs and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). If it comes to pass in the next decade or so, entry into force of the CTBT and the verification and monitoring of that agreement by the CTBT Organization would provide a valuable model in this domain for nuclear arms reductions.

Timeline and strategy. The timeline for OPLAN 2045 is compelling for both practical and humanitarian reasons. A time horizon of approximately 30 years for creating a new international security order in which nuclear weapons have been removed from national arsenals seems reasonable, but by no means certain. To succeed on the practical level, OPLAN 2045 would need to make coordinated progress across all five domains of statecraft and strategy. Given the challenges of achieving significant milestones in complex domains, 10-year increments are reasonable timespans within which more detailed schedules and plans could be defined.

For example, it may take 10 years or more for the CTBT to enter into force and another five beyond that to implement a fissile material cut-off treaty (FMCT). Both of these agreements would be logical stepping-stones to a multilateral ban on nuclear weapons, although they are not essential prerequisites. In all probability, the obstacles to nuclear disarmament that would take the longest to eliminate would be necessary changes in belief systems and in regional security arrangements.

The matrix below provides a rough example of how progress over the five domains might be made over time. (A larger version of the matrix is included as a file attachment at the end of this article.)

Decades will be needed to progress toward milestones in each of the domains, but achieving a certain combination of goals could create powerful synergy, increasing the likelihood of achieving significant next steps in more than one domain simultaneously. An example of one such event: A global nuclear no-first-use convention—with corresponding changes to nuclear force postures—could drastically reduce the role played by nuclear weapons in the strategies of all states that possess them. This, in turn, could increase universal willingness to sharply reduce the size and alert levels of all nuclear arsenals. Another example could be achievement of a nuclear weapon-free zone in the Middle East, which would be of greater significance than other, previously established such zones. Identifying “force multiplier” events is central to the OPLAN 2045 strategy.

Strategic pausing. A 30-year planning horizon also accommodates the possible need for strategic “pauses” that may be necessary in reaction to unforeseen events or to successes or obstacles in the various domains. This concept of waypoints for strategic innovation or shifts in emphasis is included in the vision of the Nuclear Security Project for achieving a world without nuclear weapons created by George P. Shultz, William J. Perry, Henry A. Kissinger, and Sam Nunn. Three or more potential pauses can be identified in the nuclear disarmament process; these are points at which go, no-go decisions will be necessary on the desirability or feasibility of the next step.

One such point may be close at hand. The failed 2015 NPT review conference, failure to bring the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty into force, and a continued lack of progress on a Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty or a Middle East nuclear weapons free-zone could cause a significant number of non-nuclear weapons states to re-evaluate their support for the Non-Proliferation Treaty. This outcome would require a strategic reassessment of the NPT as the primary legal stepping-stone to a nuclear weapons convention or other instrument banning the possession or manufacture of nuclear weapons. As mentioned above, this historical juncture may have just been crossed, and it is now necessary to coordinate the actions of the NPT process with the new initiative to negotiate a nuclear weapons ban in the UN Committee on Disarmament.

On the other hand, short-term developments could accelerate OPLAN 2045. For example, the Scottish independence movement and excessive costs could lead the UK eventually to announce the phasing out of its nuclear weapons. It is also possible, despite current tensions and obstacles, that the United States, NATO, and Russia will reach some agreement significantly reducing non-strategic nuclear weapons before 2020.

The need for a pause could also be envisioned following the achievement of a multilateral nuclear weapons reduction agreement. It is possible that the five nuclear weapons states as defined by the NPT, joined by India and Pakistan, will at some future point agree to cap or reduce their nuclear arsenals to fewer than 500 weapons each. This would require agreement on the complex tasks of verification and enforcement.

A third strategic pause might be needed before reaching international agreement on what type of legal instrument and institutional structure might finally achieve and enforce a ban on nuclear weapons and fissile materials. Should nuclear weapons be completely dismantled, or should a small arsenal be retained under international control? What about stocks of fissile material? What inspection capabilities would be needed for civil nuclear energy programs? What penalties would be imposed for violating a nuclear weapons ban? Even more fundamentally, before going to zero, the international community will need to have the confidence that deep nuclear weapons reductions have not resulted in a higher risk of major interstate warfare.

Why 2045? The year 2045 has powerful symbolic and psychological appeal as a target date for the elimination of nuclear weapons. Both the threat of nuclear annihilation and the movement to reject nuclear weapons as instruments of national security were born in 1945. The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki vividly demonstrated the terror of the nuclear age. Civilization has now lived with that terror for more than 70 years, and most human beings on Earth have now lived under that threat for their entire lives. By 2045, this will be nearly universally true.

Establishing 2045 as a goal for ending a century of nuclear terror can help energize and galvanize the campaign to ban nuclear bombs, initiated by many of the very scientists who invented them. The core ideology of this movement has always been based on humanitarian and strategic beliefs. Many citizens, scientists and laymen alike view nuclear-weapons abolition as an essential milestone in the development of human civilization.

One hundred years of nuclear fear is enough. The international community has the opportunity to honor the memory of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by eliminating nuclear weapons from the arsenals of the world within a century after they were unleashed.

Trends and assumptions. The concept for OPLAN 2045 presented above makes some major assumptions regarding future strategic trends. The first: As 2045 approaches, the perception that nuclear weapons contribute to national and international security will continue to decline, and understanding of the security liabilities they impose will increase. Simultaneously, the threat environment for most states will increasingly include challenges that can only be mitigated through collective action and to which nuclear weapons have little or no relevance.

OPLAN 2045 also assumes that the logic of nuclear deterrence and the desire for nuclear nonproliferation are ultimately mutually exclusive. If the nations possessing nuclear weapons continue over the next 30 years to claim that those weapons are essential to their security, other nations will inevitably acquire them for the same reasons. OPLAN 2045 assumes that this dynamic will become more pronounced over time, unless major changes are made in the roles that nuclear weapons play in national security strategies and states possessing nuclear arms take more genuine actions to foreswear them.

A third major assumption underlying OPLAN 2045 is that nuclear weapons use remains possible, and the risk of use rises with further proliferation. The possibility of accident, mechanical malfunction, and errors of human judgment dictate that the risk of nuclear use is constantly above zero. Over the last half-century, the number of states that manufactured nuclear weapons increased from four to 10, and quantities of weapons-usable nuclear materials have increased many-fold.

The technology for the construction of a nuclear explosive device is now 70 years old and has spread widely. Nations no longer have a monopoly on the knowledge and ability to build and use nuclear bombs. The resources and capabilities of non-state actors are increasing, and they are not deterred by the threat of nuclear retaliation. These trends are likely to continue over the next 30 years, with a concomitant increase in the risk of nuclear war, unless there is a fundamental shift away from using nuclear weapons for national defense and deploying them in prompt-use configurations.

How to define success. The initiation of OPLAN 2045 does not require a specific definition of the “elimination of nuclear weapons.” Only a general notion of the desired end-state is needed to guide initial efforts. That end state is one in which individual nations do not possess or manufacture nuclear arms or fissile materials for military purposes and do not pursue security strategies that include threats of nuclear weapons acquisition or use.

Several alternative pathways towards this end-state have been envisioned. One is the de-legitimation pathway, which seeks to deepen and mobilize humanitarian, ethical, and rational arguments against nuclear deterrence as a legitimate concept for national defense. This path is considered in the belief systems domain of the concept for OPLAN 2045. According to this path, exposing the moral and practical paradoxes of nuclear strategy and the risks and consequences of nuclear war will undermine support for nuclear deterrence among both general populations and the global political elite.

A second path is legal in orientation. It could include new international agreements such as new arms reductions treaties, a universal nuclear no-first-use agreement, a Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, and finally a nuclear weapons convention. This approach corresponds most closely with OPLAN 2045’s third domain of international diplomatic and legal structures. It is consistent with a step-by-step approach toward a world free of nuclear weapons with actions being taken when they become politically feasible.

A third path would increase interest in nuclear disarmament by revising views on the roles nuclear weapons have played in national and international security. New historical research and perspectives regarding realist conceptions of the utility of nuclear weapons have challenged the assumption that they provide tangible benefits and acceptable risks to their possessors.

To meet the objective of a world free of nuclear weapons, OPLAN 2045 should outline steps to pursue all of these pathways simultaneously. The specific details of the future world sought by OPLAN 2045 remain undefined, but that does not mean the plan lacks direction, focus, or the ability to recognize success. Rather this generality is an acknowledgement that, in its early phases, the plan must encompass an expansive conceptual and operational space with campaigns on multiple fronts. Over time, progress, setbacks, and unforeseen events will reveal certain steps that become more critical and achievable, or conversely those that must be delayed or tackled with a modified strategy. At the outset, it is sufficient to define success as incremental progress toward long-established benchmarks such as entry into force of the CTBT, further reduction of national arsenals, and expansion of nuclear weapon-free zones.

It is also important to declare potential concepts that are not consistent with a world without nuclear weapons. The most prominent of these is a proposal for replacing deployed nuclear forces with “virtual arsenals.” It has been suggested that the capabilities of various states to reconstitute nuclear forces could be regulated or managed in a manner that replicates nuclear deterrence. This concept endorses maintenance of mobilization bases for possible reintroduction of nuclear weapons including fissile materials in stock, proven nuclear weapons designs, engineers and manufacturing equipment on hand, and delivery vehicles, ready for use.

The objective of OPLAN 2045 is not to move to virtual nuclear arsenals. The concept of virtual nuclear arsenals fails to reject the ideology of deterrence based on the threat of employing nuclear weapons for national defense. Progress toward a world without nuclear weapons may include a period of time during which residual nuclear weapons, delivery vehicles, and military fissile materials exist; the objective of OPLAN 2045 is to move decisively beyond this phase to the adoption of permanent, legally-binding, verified, and enforceable prohibitions against the manufacture, possession or use of nuclear weapons.

The goal of OPLAN 2045 is to move from an era during which the acquisition of nuclear weapons was a national decision to one in which there is international agreement that these weapons should be legally prohibited for the sake of collective security. Currently, the nations possessing nuclear weapons pay lip service to the goal but seem unwilling to lead the disarmament effort with concrete measures. Correspondingly, the world’s citizens, NGOs and non-nuclear-weapon states must play a greater role, arming themselves with tools that can make their collective efforts more coordinated and effective. OPLAN 2045 is a potentially powerful tool that could be used by a range of like-minded actors to make real, measured progress toward the goal of a world free of nuclear weapons.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Analysis, Nuclear Weapons, Technology and Security