Brooke Higgins, George Mason University, graduate student,

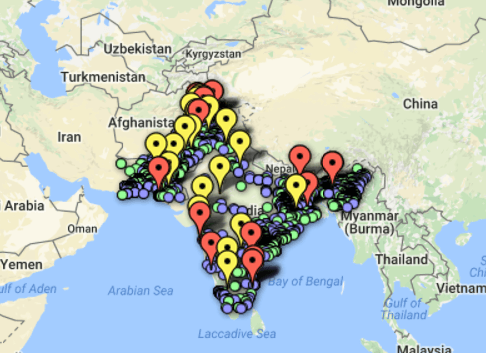

In the article, “The Terrifying Geography of Nuclear and Radiological Insecurity in South Asia,” Hannah E. Haegeland and Reema Verma conclude that terrorist means, motive, and opportunity overlap geographically with vulnerable nuclear programs in India and Pakistan creating an insecure threat environment with the potential for alarming consequences. To reach their conclusion, they created a map plotting all terrorist attacks identified in open sources in 2014 and 2015 and two other types of information—nuclear or radiological facilities and nuclear or radiological incidents. The authors write, “[f]rom the map, it's clear that sensitive materials and facilities in India and Pakistan suffer from vulnerabilities, and violent non-state actors have demonstrated the capability to carry out attacks on and around these vulnerabilities.” While I agree with the authors assessment that South Asia is an area meriting intense efforts to enhance nuclear security, their geographic information system (GIS) methodology provides a misleading portrayal of nuclear risks in South Asia. Hagel and Verma’s argument depends on the reader making an intuitive leap from their map. However, the authors’ map is poorly constructed; it overstates the prevalence of nuclear vulnerabilities vis-à-vis terrorist activity, and its underlying dataset appears to include inaccurate and incomplete information.

Because of a difference in time scaling that is not prominently explained, the map accompanying this article could mislead a reader to overestimate the prevalence of nuclear-related incidents in South Asia. The map uses red pins to draw attention to these nuclear-related events, and smaller green and blue pins to represent terrorist activity. The authors note that they mapped all open source terrorist attacks from 2014 and 2015. But the authors failed to mention that the nuclear incidents date back to 1994. In fact, only one of the 19 “red pin events” in India and Pakistan took place in 2014 and 2015. Of other 18 events, 3 occurred in the 1990’s, 13 from 2000-2009, and 3 between 2010-2014.

Omission of the timeline for nuclear events could lead a reader to reasonably infer that the nuclear incidents occurred during the same timeline as terrorist attacks mapped, and that nuclear vulnerability is much higher than it actually is. With the knowledge that the events mapped go back to 1994, the picture of nuclear vulnerability in the region changes. Rather than indicating vulnerability at a site, a red pin might actually point to a site that has strengthened security because of new measures put in place to redress a previous problem. To accurately map the state of nuclear security against the backdrop of terrorism, the events depicted should occur during the same time frame.

Beyond the map’s time-scale problem, the dataset used to create it—specifically, the nuclear events—contains multiple errors. Four of the 18 events in the dataset are incorrectly dated. The authors misspelled “Jaduguda” as “Jagugoda,” a typo that would not be particularly troublesome, if the document cited actually contained information on the nuclear incident. Instead, the document listed in the dataset as a source on the incident contains no information regarding the 2003 stolen-material incident at Jaduguda. Ironically, the 2003 Jaduguda incident would bolster the authors’ case for a nexus between terrorism and nuclear security risk, as it was the event in which Jamaat-ul-Mujahideen group members allegedly purchased 225 grams of milled uranium from a mine employee. The database also does not include two other recorded nuclear insecurity incidents: an attack in 2008 on the Kamra Pak airbase (which is suspected to have nuclear material) and a nuclear smuggling incident in 2010 in Meghalaya.

Careful analysis of the map and its underlying data reveals an incomplete picture of the nuclear security situation in South Asia. To analyze the risk of a terrorist organization’s ability to obtain nuclear material or attack a nuclear facility, one must analyze recent and specific attacks. The quantity of attacks does not indicate quality, means, or methods. Plotting one-time vulnerabilities against terrorist activity that occurred 20 years later does not necessarily lead to a conclusion that terrorists have the capability to successfully exploit those vulnerabilities today. The authors rightly point out that nuclear terrorism merits intense focus. Unsound methodology and incomplete data could undermine the work of researchers and security officials dedicated to accurate assessment of the nuclear security environment in South Asia.