Now—more than ever—is the time for creative diplomacy

By Sara Z. Kutchesfahani | February 8, 2018

At a recent event in Washington, DC, former Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz delivered a speech addressing nuclear risks facing the world today. He presented a rather bleak view of the current security environment but concluded by saying, “There is a lot of headroom for creative diplomacy.” This is especially true in the realm of nuclear issues.

In the past month alone, many nuclear-related events have made front page news, including the most recent missile false alarm in Hawaii, where residents were informed by an emergency cell phone alert that a “ballistic missile threat [was] inbound to Hawaii” and that they should “seek immediate shelter” because this was “not a drill.” For 38 minutes, many terrified residents took heed of the warning, until it was announced the message was sent in error.

With President Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un arguing who has the bigger “nuclear button” and a new Nuclear Posture Review proposing that the Trump administration add new nuclear capabilities, the nuclear threat seems much too close to becoming reality, making now seem, more than ever, the time for creative diplomacy.

The term “creative diplomacy” is of course subject to interpretation and perspective, but even a cursory overview of past diplomatic successes provides compelling and effective examples of creativity that can speak to current challenges.

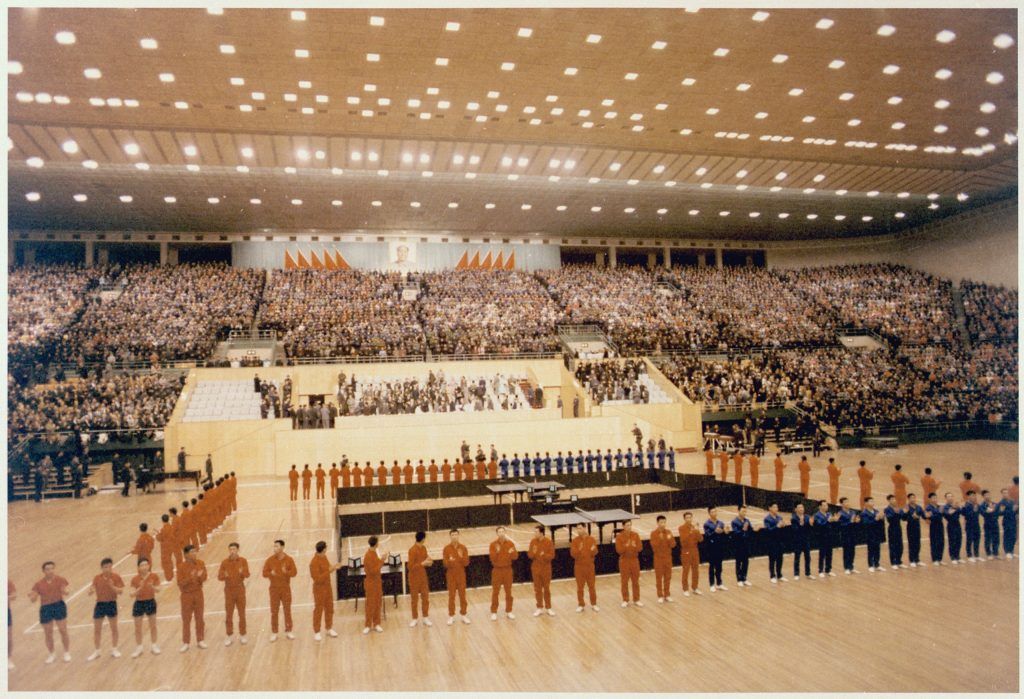

Sports diplomacy. Perhaps the most prominent example of the creative use of sports in international relations is the “ping-pong diplomacy” exercised between the United States and China in the 1970s. The exchange of table tennis players of the two countries resulted in a thaw in relations that helped pave the way for President Richard Nixon to visit Beijing. One American table tennis player who participated in the exchange remarked, “People are just like us. They are real, they’re genuine, they got feeling. I made friends, I made genuine friends, you see. The country is similar to America, but still very different. It’s beautiful.”

Ping-pong is hardly the only diplomatic sport. In the 1998 World Cup, Iran was matched against the United States. It was 19 years after the Islamic Revolution and the takeover of the US embassy in Tehran that had deeply soured relations between the two nations. Over the years, few attempts were made to normalize relations; in 1998, tensions between the two nations remained very high. The game was described as the most politically charged in World Cup history, with the president of the US Soccer Federation calling it “the mother of all games.” The two teams shook hands with one another, while the team captains exchanged gifts from their respective nations. The game itself was very competitive, but fair, and Iran won 2-1. The players recognized the historical role they played, with US defender Jeff Agoos concluding, “We did more in 90 minutes than the politicians did in 20 years.”

More recently, the announcement that North and South Korean athletes will walk together under one flag at the Winter Olympics and the two nations will field a women’s ice hockey team together is encouraging. And ping-pong, soccer, and now ice hockey by no means exhaust sports diplomacy possibilities. There are enough other competitive sports to cover all 193 UN-recognized countries and sustain creative diplomacy.

Cultural diplomacy. The exchange of ideas, information, art, and other aspects of culture among nations and their citizens can foster mutual understanding and appreciation. Popular culture and art play an important role in understanding how a country is perceived by the outside world. In 2007, for example, the State Department’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs sponsored a cultural exchange of 14 young Iranian artists for a three-week visit to the United States. The Iranian artists toured museums and galleries and met with local artists across the country. The work of the Iranian artists went to nine US cities, giving Americans across the nation an insight into life in Iran. President Trump’s travel ban (Executive Orders 13769 and 13780) prohibits citizens of eight countries, including Iran, from entering the United States. The ban would need to be rescinded if the United States decided to resume the State Department’s 2007 efforts to engage Iran in cultural diplomacy.

Confidence-building measures. Throughout the 1950s and ‘60s, the international community suspected Argentina and Brazil of pursuing covert nuclear weapons programs. For 11 years (1980-1991), Argentine and Brazilian nuclear experts (policy makers and scientists, governmental and non-governmental) engaged in sustained dialogue, as well as in trust- and confidence-building measures, including high-level presidential and technical reciprocal visits to unsafeguarded and sensitive nuclear facilities. Opening these facilities to the scrutiny of a delegation headed by the two countries’ presidents allowed both leaders to announce a new policy based on openness in nuclear issues.

Ultimately, the support and will of the political leadership helped establish the Brazilian-Argentine Agency for the Accounting and Control of Nuclear Materials (ABACC). ABACC, the world’s only existing bilateral mutual safeguards inspection agency, verified Argentina and Brazil’s non-nuclear weapon status. It serves as an example of how confidence-building measures can help build a necessary element of trust between two rivals.

Bi-partisan congressional diplomacy. Perhaps the best example of bipartisan congressional diplomacy in the nuclear weapons realm is the Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) Program, which facilitated the removal of nuclear weapons from Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine after the fall of the Soviet Union. In 1991, Democratic Sen. Sam Nunn of Georgia joined forces with Republican Sen. Richard Lugar of Indiana to propose legislation that would safely and securely dismantle nuclear weapons in those three former Soviet republics. The CTR Program was crucial for deactivating more than 7,600 nuclear warheads, destroying 900 intercontinental ballistic missiles, and demolishing 700 submarine-launched ballistic missiles. Most important, today Belarus, Kazakhstan and Ukraine are nuclear-weapons-free because of the program. CTR is one of the greatest examples of successful non-proliferation efforts the world has seen. With nuclear risks increasing by the day, the time may be ripe for a CTR 2.0.

Face-to-face diplomacy. One of the key lessons learned from the creation of the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), often known as the Iran nuclear deal, was the importance of sustained in-person dialogue. New Yorker contributor Robin Wright surmised that despite an eventual rapport between US and Iranian envoys, the JCPOA talks nearly collapsed at least five times in their final nine months. Yet, the talks continued, and they continued face-to-face. According to a State Department official, during his two-and-a-half years as secretary of state John Kerry logged more time one-on-one with his Iranian counterpart Javad Zarif than with any other foreign minister.

This example may be worth remembering as US policymakers continue to refrain from talking to their Russian—and indeed North Korean—counterparts. Instead of US policymakers sitting in DC thinking about how [insert your favorite non-US ally here] thinks about nuclear weapons, they should be talking to that country. That is the way to figure out how to reduce nuclear threats. As former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill remarked, “To jaw-jaw is always better than to war-war.”

The road ahead. From sports to art and culture, from confidence-building measures to bipartisan congressional initiatives and face-to-face dialogue, there is a recurring theme in creative diplomacy: human interaction. The personal relationships that develop from direct interaction matter, because they have proven time and again to be productive even in the most difficult situations.

Indeed, we are reminded of this fact by a character in Oslo, a 2017 play, written by J.T. Rogers, that tells the true story of the back-channel talks, unlikely friendships, and quiet heroics that led to the 1993 Oslo Accords between the Israelis and Palestinians. In it, the Norwegian academic Terje Rød-Larsen tells his Israeli and Palestinian guests, “For it is only through the sharing of the personal that we can see each other for who we truly are.” It is once again time to get personal, be creative, and pursue diplomacy.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Nuclear Weapons, Opinion, Special Topics