Where does Trump get the power to reimpose sanctions?

By Aaron Arnold | August 15, 2018

What is the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA)?

What is the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA)?

Last week, the Trump administration reimposed unilateral sanctions against Iran. This comes after the administration announced its intention to withdraw from the Iran deal in April, despite compelling reasons not to. Like most of America’s sanctions regimes, Trump’s order to reimpose sanctions rests on authority granted under a little-known and even less understood statute that gives the president sweeping authority to regulate certain aspects of international trade and commerce: the International Emergency Economic Powers Act

What is it? Perhaps better known by its acronym, IEEPA (pronounced: eye-e-puh) is the 1977 Congressional legislation enacted to limit the president’s national emergency powers.

Oddly, though, it has done the exact opposite.

Prior to IEEPA, the president used the authority granted to him under the 1917 Trading With the Enemy Act to regulate international trade and commerce in times of national crisis. The problem, however, was that the 1917 act was not entirely clear in terms of its scope and duration. In fact, Richard Nixon used the statute in 1970 to call in the National Guard to deliver mail during a postal-workers strike. Many in Congress saw this as executive overreach, and moved to limit when the president could use the Trading With the Enemy Act—hence, IEEPA.

Practically, IEEPA and the Trading With the Enemy Act are the same, but with one notable difference: While the United States must be in a state of war for the president to regulate trade and commerce under the Trading With the Enemy Act, the President has complete discretion to declare a national emergency under IEEPA. The only requirement is that the emergency be an “unusual and extraordinary” threat that emanates in whole or substantially outside of the United States. What exactly constitutes “unusual” or “extraordinary,” however, is up for interpretation.

Once the president declares a threat, he can investigate, regulate, or prohibit a range of transactions and economic activities with few exceptions —primarily related to humanitarian aid and education materials.

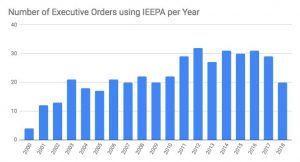

What can the president do under IEEPA? Perhaps a better question is, what can’t the president do under IEEPA. Since its passage, presidents have relied on IEEPA to enact financial and economic sanctions against a host of countries, including Iran, North Korea, Syria, South Sudan, Russia, and Cuba to name a few, for threats ranging from terrorism and narcotics trafficking to human rights violations and WMD proliferation. One of the first uses was against Iran in 1979 over the hostage crisis. Signed by then-President Jimmy Carter, the sanctions froze Iranian assets and properties within the United States. In fact, since 2000, Presidents have used IEEPA in more than 400 executive actions. Not all of these actions were new, however. Some extended the timetable or expanded the scope of previous orders.

As the frequency of use of IEEPA has increased, so too has its scope. Executive Order 13382, for example, which President Bush signed in 2005, freezes assets and blocks transactions, within US jurisdiction, of those who contribute to the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. In September 2017, President Trump signed Executive Order 13819, which expanded the financial and economic sanctions against North Korea. The latter, however, included several extraterritorial provisions, which threatened what amounts to secondary sanctions on any foreign entity that conducts business with North Korea— not just US businesses and interests.

Who enforces IEEPA? For sanctions imposed under executive orders that rest on IEEPA authorities, it is the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC) that is responsible for maintaining lists of designated individuals and companies, as well as implementing regulations and enforcing violations. Running afoul of sanctions may incur regulatory penalties such as fines, but there are also criminal penalties for violating IEEPA.

Federal law enforcement agencies, like the FBI, DHS Homeland Security Investigations, and the Commerce Department also investigate IEEPA violations—generally dealing with export violations. Per the statute—not the corresponding implementing regulations—violations or conspiracies to violate IEEPA can result in criminal penalties. In fact, violating IEEPA is also considered a predicate offense (i.e., the beginning of a larger criminal offense scheme) for financial crimes, meaning that IEEPA violations can also incur money-laundering charges, which have far stiffer penalties. This was exactly what happened in several recent cases against Chinese companies that provided intermediary financial services for North Korea.

In August 2017, Federal prosecutors filed a criminal complaint against Dandong Zhicheng Metallic Material Co., Ltd.—a China-based company—for its role in helping North Korea evade sanctions.

IEEPA gives the President extraordinary powers, but is it too much? Thus far, Congress has left presidents’ use of IEEPA relatively unchecked. The exception has been the occasional piece of legislation, like the Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability, and Divestment Act of 2010 , which essentially codified certain executive orders— removing some (but not all) discretion from the president. From a legal perspective, there have been few successful challenges of IEEPA. So far, conducting US foreign policy through a broad interpretation of national security powers has always been the prerogative of US presidents.

But as European leaders scramble to save what is left of the Iran deal, many are left wondering whether a president that wields IEEPA like a hammer will see every problem like a nail. Clearly, IEEPA is a useful legal authority to preventing the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, but it is also an instrument best used and most effective when there is a multilateral consensus. It is doubtful that continuing to project American foreign policy, using IEEPA, will result in anything but a reaction by our allies to insulate themselves against US exposure.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Iran, Iran agreement, sanctions

Topics: Analysis