Censorship 101: China’s young censors first have to learn about forbidden topics

By Matt Field | January 3, 2019

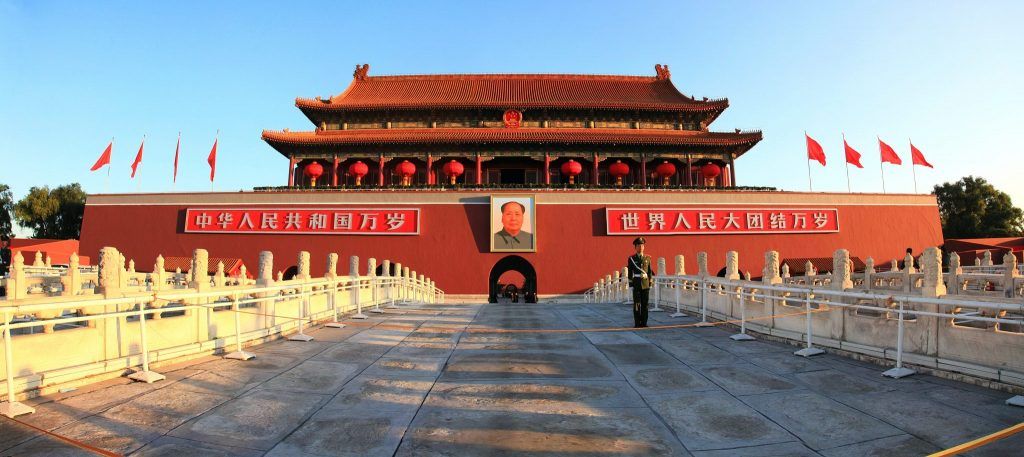

Tiananmen Square.

Tiananmen Square.

Li Chengzhi, a young college graduate in Chengdu, China, shows up to each of his work shifts at a bright new office in “the heart of a high-tech” part of town. But Li’s job isn’t to harness the power of new technology to change the world–it’s to maintain the status quo. Li is one of thousands of censors working at firms in China tasked with making sure internet users don’t learn unsavory facts about anti-democracy crackdowns or government scandals.

The New York Times featured Li in a recent article about China’s censors, many of whom work for firms, like Li’s, that censor content on behalf of client companies. Full of fascinating detail, the article describes the firm, Beyondsoft, which employs 4,000 people to monitor for politically sensitive or offensive content. For censors like Li, the first step is on-the-job training to learn about all the topics internet users in China aren’t supposed to encounter, including, for instance, the Tiananmen Square crackdown in 1989.

The young employees at Li’s Chengdu office are “often unaware of, or indifferent to, politics.” Yang Xiao, internet service head at Beyondsoft, tells the Times, “I often hear the surprised sounds of ‘Ah, ah, ah.’” Referring to the Tiananmen Square crackdown, Yang says of the young employees, “They really didn’t know.”

Chinese internet users are notoriously crafty at getting around censors. For instance, at one point, some were employing pictograms using Chinese characters that look sort of like tanks squaring off against protestors. This is, of course, a scene that played out during the Tiananmen Square protests. While censors do employ artificial intelligence to root out forbidden content, the applications aren’t yet as good as a pair of human eyes, Li says.

While activists, elected officials, and many others in the United States decry China’s internet censorship, US tech companies appear eager to do business in China. Google is weighing whether to create a censored search engine dubbed Project Dragonfly. CEO Sundar Pichai downplayed the significance of the project in a congressional hearing last month, calling it a “limited effort internally, currently.”

Does Li tell others about the forbidden content he learns about during his training? “This information is not for people outside to know,” he says.

Publication Name: The New York Times

To read what we're reading, click here

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Censorship, China, Google, Tiananmen Square

Topics: Disruptive Technologies, What We’re Reading