When Doomsday comes, Americans will tweet

By Thomas Gaulkin | February 26, 2019

Adapted from Shutterstock and Rosaura Ochoa (Flickr/Creative Commons)

Adapted from Shutterstock and Rosaura Ochoa (Flickr/Creative Commons)

Nuclear missiles are inbound. Even the smallest payload can destroy your whole world. You will never see the people you love again. So, like thousands of others facing their last moments on Earth, your first instinct is to start tweeting.

Sounds like the setup for a post-apocalyptic Darwin Award. But it’s the serious point of departure for a new report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, published just a week before Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un meet again to discuss what might be done about those warheads that can apparently reach the United States.

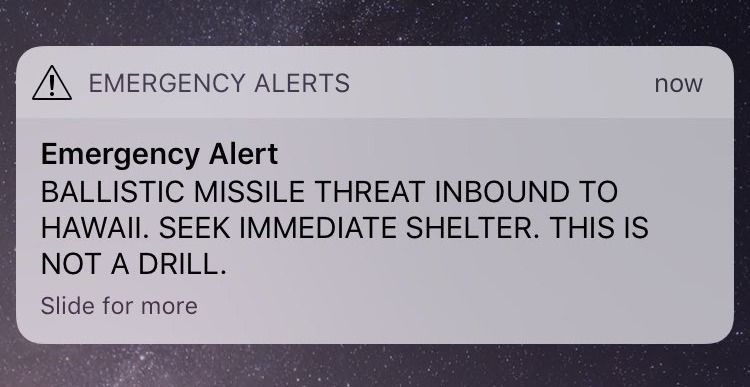

Examining patterns on Twitter during the January 13, 2018 false alert that warned Hawaiians of an impending ballistic missile strike from North Korea and made the “unimaginable tangible,” the study reveals as much about preparedness for nuclear attack as it does about 21st century social norms.

Sirens going off in Hawaii, ballistic missile threat issued. What’s happening?

— Iain Alexander (@iain_alexander) January 13, 2018

Published, fittingly, in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, the report compiles more than 14,000 tweets that mentioned “missile and Hawaii,” “ballistic,” “shelter,” “drill,” “threat,” “alert,” or “alarm” on the morning of the alert. (The authors excluded tweets shared more than once, like quoted tweets and retweets—adding them back in increases the count of human beings who were more firmly concerned about their online status than their biological status to as many as 125,000).

The CDC breaks their substantial sample of tweets into two broad categories covering the first 38 minutes after the alert was sent, followed by a “late period” after it was cancelled. Within these groupings, tweets reflect various stages of social media grief like “information processing,” “emotional reaction,” and after the retraction, “denunciation” and “mistrust of authority.”

Unsurprisingly, the researchers’ findings confirmed that “some social media users lacked awareness about actions to take when faced with a nuclear threat.” Sent a phone message like this:

…many Twitter users justifiably panicked. One tweet cited by the report offers a vivid example of what happened next in the Aloha state that morning: “my friend & i were running around the hotel room freaking out because HOW DO WE TAKE SHELTER FROM A [expletive deleted] MISSILE?!” And it’s hard to argue with the report’s view that this Lakers fan demonstrated “mental processing of the alert”:

Idk what’s going on… but there’s a warning for a ballistic missile coming to Hawaii? Wtf

— Thai Luong (@thailuong33) January 13, 2018

Fortunately, all of these people are still alive (though in at least one case, the alert itself could have been deadly). And, as discussed on this website before, the researchers see their findings as evidence that better messaging can help: “Social media provides public health authorities with the capability to convey timely messages, address societal reactions during each phase of a crisis, and establish credibility to avoid mistrust and denunciation of a public health message.”

But the bottom line is that most people living in the United States still have little comprehension of the risk posed by nuclear weapons or any actions that might minimize it, and relying on friends’ tweets (or elected officials‘) is probably not going to cut it in a real emergency. As the CDC authors conclude, “additional research is needed to understand human reactions to emergencies in the social media age so that timely public health messages can be developed and disseminated to save lives.”

After the crisis in Hawaii was over, the state’s Emergency Management Agency quickly reassigned and then fired the employee who sent the alert, noting that the unnamed worker had previously “confused real life events and drills” and had been “unable to comprehend the situation at hand.”

It’s not exactly comforting that the same could be said of at least 14,000 Twitter users that day.

Can you imagine waking up to an alert that says. “Take shelter there is a missile on the way” like Bruh. What shelter is there for a missile? That Shit might as well say. “Aye Bruh. Missile on the way. Good luck”

— Fat boy La Flare (@PartyAnimalKO) January 13, 2018

Publication Name: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report

To read what we're reading, click here

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Nuclear Risk, Nuclear Weapons, What We’re Reading

most people are starving the most precious commodity of all time

even if you should survive the blast

the aftermath is probably not worth living through a long pathetic painful death

people don’t get it is beyond comprehension