A congressional effort to coordinate US nuclear nonproliferation efforts. From a Republican.

By Thomas Gaulkin | March 22, 2019

Illustration by Thomas Gaulkin

Illustration by Thomas Gaulkin

The Trump administration’s 2018 Nuclear Posture review was so short on nonproliferation that a Republican congressman is proposing a new government body to address it.

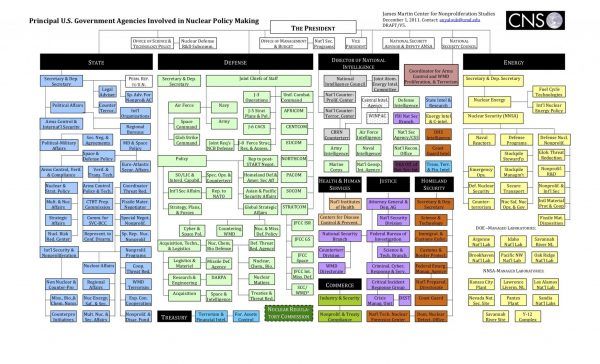

US Rep. Jeff Fortenberry told the Bulletin he will soon introduce legislation in the House of Representatives creating a Nuclear Nonproliferation Council to coordinate US government agencies’ work on securing nuclear material and preventing the further spread of nuclear weapons. It is conceived as “a formalization of the network of nonproliferation actors within the government,” said Fortenberry, who represents Nebraska’s first congressional district.

The proposed council would complement the existing Nuclear Weapons Council (NWC) established by Congress in the 1987 National Defense Authorization Act. The Nuclear Weapons Council serves as the focal point of Defense Department and National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) coordination on maintenance of the US nuclear weapons stockpile—including major portions of the $1.7 trillion nuclear modernization program currently underway.

Fortenberry first presented the concept for the new council in an October 2018 post on his congressional website. “Numerous outside organizations, from independent commissions to the Government Accountability Office, have voiced concern about the level of coordination between these nonproliferation entities and the activities they oversee,” he wrote. “I have proposed a parallel entity called the Nuclear Nonproliferation Council, whose purpose will be to examine what we are doing and give us the highest possible assurance that we are preventing the spread of nuclear weapons technology and materiel.”

Current government coordination on nuclear nonproliferation policy is a maze, Fortenberry told the Bulletin. “Due to the good people who’ve dedicated themselves to this space, we’ve actually carried forward a body of wisdom inside our government, and I think that’s been important,” he said. “But, from my perspective, formalizing that through a peer-to-peer type of council that could actually do a better reporting job to Congress on what’s going on […] would be a good development.”

“Why not have a parallel nonproliferation council to formalize what are already good, robust interagency activities?” Fortenberry said.

Fortenberry’s office expects the legislation to be introduced in the next month. No details about the scope of the proposed council’s activities and membership were on offer while the legislation is still being drafted, but Fortenberry sees the council as part of the United States “trying to lead the world in a new architecture” for reducing the possibility of a nuclear exchanges as well as the risk of nuclear accidents or theft of nuclear material that can be used for dirty bombs.

Fortenberry also noted the proliferation concern posed by nuclear technology exports—a problem highlighted by the multiple controversies surrounding Saudi Arabia’s nuclear energy ambitions, for example. “When you sell nuclear power without significant safeguards, you’re creating a body of scientific knowledge,” he said. “And through a few switches and the right type of material, you’re in the nuclear weapons business.”

Fortenberry envisages that the nonproliferation council could address these issues from a diplomatic, as well as operational perspective. “In my view, nonproliferation is a big word that encompasses a lot of things,” he said. “It has certain technical definitions that we say around here in terms of nonproliferation of weapons and nonproliferation of possible materials use… Technically that’s what we’re trying to focus on with this piece of legislation. But it’s a platform for entering into a lot of the softer science of diplomacy as well as the geopolitical nature of the 21st century.”

Fortenberry’s idea for a nonproliferation council has not been widely reported. He mentioned it briefly at a June 2018 appropriations committee meeting (calling it a “whole of government approach”), in the October post on his website (in which he also pointed out the Bulletin’s Doomsday Clock is now set to two minutes to midnight, “the closest we have been to colossal extinction since the height of the Cold War”), and most recently in an end of year report presented to the House this past January.

Fortenberry said he began working on the idea for a nonproliferation council last spring after reading through the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR). “It just struck me as peculiar that perhaps 95 percent of it was dedicated to atomic weaponry. I think there were about two pages dedicated to nonproliferation,” Fortenberry said. “I thought it was a peculiar under-emphasis on nonproliferation. And that is a significant part of keeping us safe.”

Among the NPR’s recommendations was a call for production of new weapons like a modified submarine launched warhead with a “low” yield of about five kilotons, and a nuclear-armed sea launched cruise missile. Many of the stockpile improvements suggested by the NPR derive from assessments and decisions of the Nuclear Weapons Council, whose voting members include two under secretaries of defense, the Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the NNSA administrator, and the commander of US Strategic Command (STRATCOM).

Fortenberry’s Nebraska district includes the headquarters of STRATCOM, which oversees the nation’s strategic deterrence and nuclear weapons operations.

“I’ve been a supporter of modernization and regeneration for our own safety and defense posture as a part of deterrence,” Fortenberry said. “On the other side of the coin, though, is to ensure that we are aggressively working for nonproliferation. … I just thought since we had an Atomic Weapons Council [sic] that led to significant recommendations about how we modernize and assure our deterrence, that we ought to have at least some kind of corresponding emphasis on nonproliferation. And I decided to try to venture into the legislative round and formalize this through a nonproliferation council.”

Fortenberry created and leads a bipartisan caucus called the Congressional Nuclear Security Working Group focused on nonproliferation issues. The group was instrumental in passing an amendment to the 2019 National Defense Authorization Act that directed the NNSA to speed the elimination of cesium chloride, which can be used to make dirty bombs, from medical equipment in the United States. The group’s co-chairs are Fortenberry, fellow Republican Rep. Chuck Fleischmann, and Democratic Reps. Bill Foster and Ben Ray Lujan.

“We dialogue with the Department of Energy, with NNSA regularly,” Fortenberry said. “We’ve had the highest level of meetings, particularly with Energy—with Secretary [Rick] Perry as well as [Ernest] Moniz prior to him. It creates the conditions for some type of movement around these ultimate existential questions which really, really get short shrift around here.”

Asked how political divisions in Congress might affect support for the proposal—particularly in light of disagreements over the NPR and the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Iran deal—Fortenberry acknowledged that “distinctions of approach” exist on nuclear policy. There is also some resistance to another bureaucratic entity within Congress, he said. But he sees the proposed council as an opportunity to engage in bipartisan work on an existential concern.

“This type of issue should transcend any political disagreement,” Fortenberry said. “It really is about life and death, the future of civilization itself.”

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Nuclear Risk, Nuclear Weapons