Sri Lanka blocked Facebook after the Easter bombings, but was social media really a problem?

By Matt Field | April 29, 2019

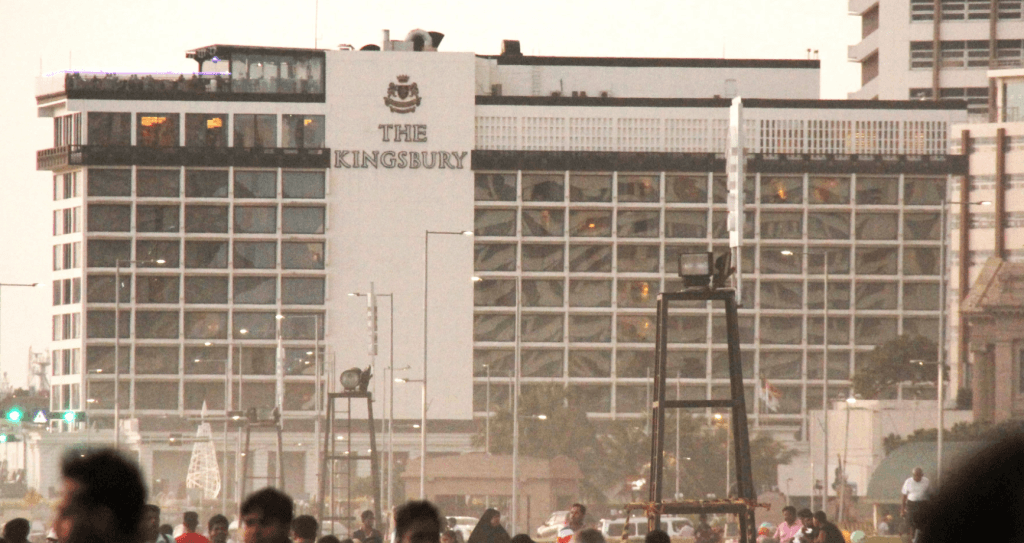

The Kingsbury was one of the Sri Lankan hotels and churches targeted by suicide bombers on April 21. Credit: AKS.9955 via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0. Cropped.

The Kingsbury was one of the Sri Lankan hotels and churches targeted by suicide bombers on April 21. Credit: AKS.9955 via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0. Cropped.

In the wake of the April 21 bombings in Sri Lanka that killed about 250 people, the government there took the unusual step of blocking Facebook and other social media. In 2018, Sri Lanka did the same thing to clamp down on anti-Muslim riots. This time, the government seemed to act on the presumption that hateful rhetoric would spread online and certainly lead to real-world violence.

Sri Lankan authorities shut down Facebook and other sites after the bombings ostensibly to prevent a repeat of the wave of rioting that roiled the country in 2018. According to Freedom House, a Washington, DC-based think tank, disinformation on social media was central to fueling the violence in 2018. This time around, The Washington Post reports that researchers again saw misinformation, including hoaxes that misidentified those responsible for the bombings, beginning to spread.

People in the United States began to appreciate just how corrosive a role social media could play following the 2016 elections, during which Russian agents orchestrated a massive disinformation campaign in an attempt to help President Donald Trump. As Frontline reported last year, Americans were just learning a lesson about Facebook that people in places like Ukraine had known for years.

Following last month’s mosque shootings in New Zealand, which once again cast Facebook and other platforms as conduits for extremists to spread hate and violent rhetoric, Australia passed tough new regulations on social media content. Sri Lanka shut down social media in an atmosphere of widespread questioning of how the platforms are affecting democracy and other aspects of society in countries around the world. But was shutting social media down in Sri Lanka a good or even effective way of controlling hate and violence?

The Bulletin talked with University of Chicago political science professor Paul Staniland, who researches political violence in South Asia. Staniland takes a nuanced approach to thinking about social media in Sri Lanka—arguing essentially that it’s difficult to pin the country’s problems entirely on the services. President Maithripala Sirisena extended the block past April 26, when it was supposed to end, saying there was still too much misinformation on social media.

The following email interview has been edited for length and style.

How do people view social media in Sri Lanka? Do they perceive it mainly as having negative consequences?

The most violent revolts and riots in Sri Lanka’s history predate social media–years like 1915, 1956, 1971, 1983, and 1987, among others, come to mind as moments of particularly intense conflict, without Facebook or Twitter. I think there can be a tendency to exaggerate the specific causal role of social media in driving violence.

The same is true elsewhere in the world: while social media can make things worse, it’s simply not the case that conflicts in India or Myanmar have emerged due to social media. They have much deeper historical roots and mass violence has been very possible prior to the social media era.

I’m certainly not advocating that we ignore how social media can spread hatred or violence. But I am suggesting that it’s not as straightforward as we might assume, and thinking about technological solutions to political problems won’t be successful. We need to think more carefully about when social media simply tracks existing biases and political conflicts, as opposed to when it actually creates new polarizations.

There is misinformation and hatred on Facebook in the United States. What if anything is different about how those phenomena spread online in Sri Lanka?

I’m not sure there’s a huge difference. Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp are key applications in Sri Lanka. Sinhala is of course vastly more prevalent as a language, and smart phones may be even more popular as the primary way to get online. I don’t think we want to assume that the internet is intrinsically different outside of the United States–there are different politics surrounding broadly similar technology, and those politics drive how the technology gets used. (This is an interesting study of hate speech on Sri Lankan social media for those who are interested.)

Do political parties in Sri Lanka campaign on social media and are their activities calm and conducive to a stable democracy?

Parties and politicians do use social media to campaign. It’s interesting the extent to which politicians have started taking to social media in recent years. Some of the buck-passing and political feuding about responsibility for intelligence and security failures has been carried out on Facebook. To the extent that this improves transparency, it’s good. Social media in general has become a standard tool of campaigning across South Asia–Imran Khan, the current prime minister of Pakistan, and his party were very savvy on social media, as has been the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) of Narendra Modi in India.

However, social media campaigns by candidates, parties, and affiliated accounts can be politically polarizing, deploying language and symbols that heighten political polarization (as during the 2015 election campaign in Sri Lanka).

Does Sri Lanka’s decision have any impact on how other countries in the region will regulate social media if and when problems crop up within their borders?

I think Sri Lanka is seen as one of a number of test cases of whether social media can be regulated and managed in very polarized political environments. In an interesting way, though, as new forms of social media emerge, we will be faced with a constantly shifting set of challenges–the last social media-linked crisis may be quite different than the next one.

Has Facebook worked to address any of the issues Sri Lankans had with the service since the government shut it down in 2018?

Facebook does seem to have invested much more heavily in the problems of incitement and hate speech since 2018. The question is whether it will ever have sufficient linguistic expertise, technical sophistication, political savvy, and contextual knowledge to manage its platform in the midst of extraordinarily complex and rapidly changing crisis situations.

Without access to Facebook and WhatsApp what information sources are left for Sri Lankans and how would you characterize their quality?

I would not characterize the rest of the media as straightforwardly neutral purveyors of solid information. This is why social media is a more complex issue–if the rest of the media were simply, neutrally providing clearly accurate information, then we could frame social media as a wild domain of fake news and prejudice. But that vision of the media doesn’t apply to Sri Lanka, or much of the rest of the world. Before the rise of social media (and after), newspapers have been perfectly capable purveyors of rumors and lies; television news is a highly effective way to convey messages that are essentially propaganda; though its effects remain debated, “hate radio” in Rwanda used a very similar technology to rapidly spread very dangerous messages.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Easter bombings, Facebook, Paul Staniland, Sri Lanka, social media

Topics: Analysis, Disruptive Technologies

Fb sole argument is that it is simply a platform, thus relieving it of any responsibility to verify facts that are posted ..let alone the sources themselves. The Als used immediately target susceptible and like minded fb participants, thus segregating political opinions-information. One could be victim to nationwide character assasination and not “see it”…not being recipients of such same posts that do the damage, being kept in the dark, and why is Libel not a crime in the USA? Why isn’t the US President sued/charged with inciting violence, and co-conspirator in murder per speeches and comments aired on national tv,… Read more »

Disagree with above. Facebook is a medium to amplify hateful messages (and neutral messages as well, but hateful/incendiary messages track more traffic). It makes common logical sense to kill/restrict the medium as a measure to control the spread. This is irrespective of the “deeper” societal issues that creates this hate. Of course there are deeper issues! Let’s not confuse and propose long term solutions for short term measures of control. If someone has a stroke you don’t say it’s a complex issue of unhealthy lifestyle choices, you first try to administer CPR immediately.