An interactive look at the algorithm powering the justice system

By Matt Field | October 18, 2019

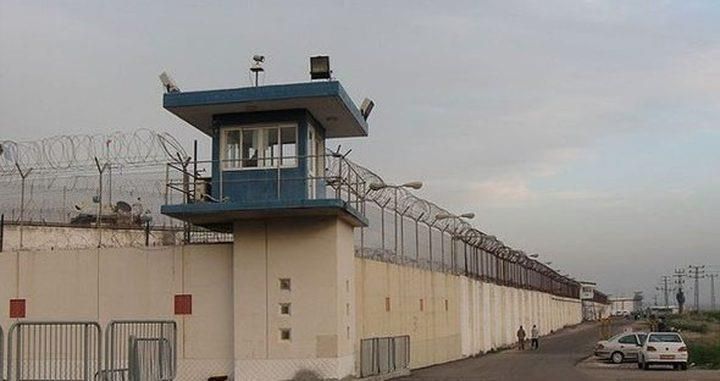

A prison in Israel. Credit: Ori via Wikimedia Commons.

A prison in Israel. Credit: Ori via Wikimedia Commons.

As artificial intelligence applications come to play a bigger role in law enforcement and military decision-making, elected officials, activists, and researchers are focusing more attention on the biases that are contained in the algorithms and big data that power AI programs. After all, if an algorithm can send police to your doorstep or flag your road trip for the military, it should at least be accurate.

But as more research and reporting is showing, powerful artificial intelligence programs can fall short in terms of accuracy, at times exhibiting racial and other biases. A new interactive piece in the MIT Technology Review highlights the shortcomings of a program used in US criminal courthouses to help decide whether defendants awaiting trial are released or kept locked up. The article’s interactive features allow users to fiddle with the figurative dials of a simplified pre-trial release algorithm and see the impact of their decisions.

The simulation is based on real data from Broward County in Florida, which uses a program called Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions, or COMPAS. It’s one of several such risk assessments used across the country. The Florida data shows, among other information, the risk score defendants received from the program and whether they were rearrested while waiting for their trials to start. COMPAS gives defendants a risk score from 1 to 10, with 1 indicating essentially a 10 percent chance of rearrest, 2 a 20 percent chance, and so on.

The company that produces the assessment, Northpointe, sets the “high risk” threshold at a risk score between 7 and 8, according to the Technology Review piece. The first thing a user is likely to notice when working with the Technology Review’s interface is that defendants in every category of risk ended up getting arrested again while awaiting trial. And among even the highest-risk defendants, there were people who didn’t end up getting rearrested ahead of their court case.

As users set the bar higher or lower for granting release, they can see how the accuracy of the algorithm fluctuates. One observation: It’s hard to be very accurate. At best, users can set the risk assessment threshold to a level that gets it right just 69 percent of the time. Another conclusion: Even when the threshold is set to the same risk level for black and white defendants, the algorithm will needlessly jail more black people than white people; it will also wrongly release more white people than black people.

Go to the Technology Review piece. Play judge and tweak the pre-trial release algorithm, finding out for yourself that it’s hard to achieve an accurate or fair result. Then think about the other ways artificial intelligence is being used in weighty decision-making—say, the Pentagon project to use computer vision to pick out threats from drone footage and other sources. If it’s hard for artificial intelligence to accurately assess whether a defendant should get released from jail while awaiting trial, how accurate will AI be at finding the right military targets, the few insurgent combatants scattered among the hundreds or thousands of innocent citizens?

Publication Name: MIT Technology Review

To read what we're reading, click here

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: COMPAS, Project Maven

Topics: Artificial Intelligence, Disruptive Technologies, What We’re Reading