Just what is carbon offsetting? And how is it supposed to work?

By Fiona Harvey | May 18, 2021

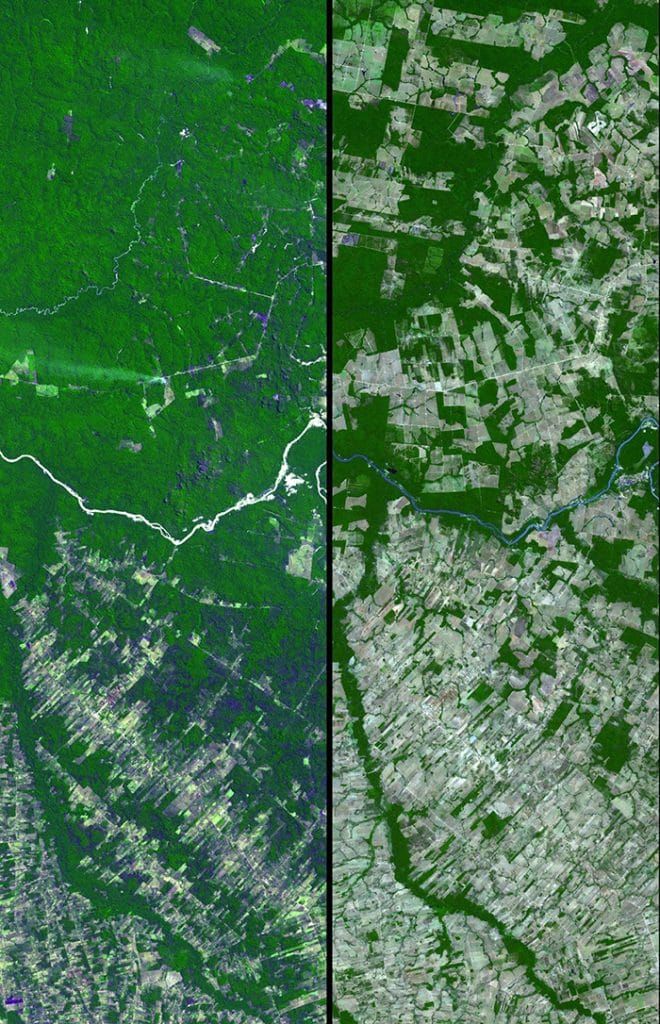

Dense green vegetation gives way to pale fields in these before-and-after satellite images of deforestation in Brazil's Amazon rainforest, taken 14 years apart. Image courtesy of NASA/GSFC/METI/ERSDAC/JAROS

Dense green vegetation gives way to pale fields in these before-and-after satellite images of deforestation in Brazil's Amazon rainforest, taken 14 years apart. Image courtesy of NASA/GSFC/METI/ERSDAC/JAROS

Editor’s note: This story and its companion piece, “Carbon offsets—popular with airlines to make net zero claims—seriously flawed” was originally published by The Guardian. It appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

What is carbon offsetting?

Carbon dioxide has the same impact on the climate no matter where it is emitted and what the source, so if a ton of carbon dioxide can be absorbed from the atmosphere in one part of the world it should cancel out a ton of the gas emitted in another. Trees absorb carbon dioxide from the air as they grow and store it, making forests one of the biggest carbon sinks.

So, in theory, companies and individuals can cancel out the impact of some of their emissions by investing in projects that reduce or store carbon—forest preservation and tree planting among them. But carbon credits are also awarded for projects that reduce fossil fuels in other ways, such as windfarms, solar cookstoves, or better farming methods.

So companies can buy their way out of climate trouble with carbon credits?

Yes and no. Carbon credits should not be used as an excuse to put off the systemic reforms to our energy generation and usage that are urgently needed—ultimately, we must reduce emissions drastically to prevent catastrophe, and offsetting alone will never achieve that. To opponents, carbon credits and carbon trading are a distraction while we dither over the systemic reforms. To supporters, offsetting and the sale of carbon credits produce a flow of money to developing countries to help them preserve carbon sinks and develop their economies along low-carbon lines.

Can’t we just plant more trees?

Planting more trees is one answer, and there are plans in many countries to do so. But while deforestation continues, planting trees cannot make up for the carbon lost when standing forests are cleared—and cannot replace the lost populations of wildlife, plants, and other species, or the damage to the people who call the forests home.

What is REDD+?

The world is losing more than 18 million acres (7.3 million hectares) of forest every year, the equivalent of 27 football fields every minute, which causes a vast reduction of the planet’s carbon sinks, as well as a staggering loss of biodiversity. Most of the world’s remaining dense tropical forests are in developing economies with tens or hundreds of millions of people living in dire poverty. They face a dilemma: allow loggers and industrial interests to cut down forests, perhaps replacing them with commercial plantations, or lose out on potential economic growth.

REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation) aims to provide forest owners with an alternative to logging and exploitation, by allowing them to raise money for protecting forests based on the carbon value of keeping forests standing or restoring them to health. REDD+ schemes help forest owners calculate the carbon value of their forests, according to agreed-upon criteria, and sets out a system of rules by which carbon credits can be issued when forest owners avoid deforestation or restore damaged forests.

Avoiding deforestation sounds good. Why is it controversial?

REDD+ and similar schemes do not mean an end to deforestation. Areas of forest can qualify for carbon credits and be used as carbon offsets even when logging still occurs within them. In some cases, loggers take the highest value trees—such as hardwoods valued for their timber—and leave most of the rest standing. In others, they agree to take wood at a lower rate than the deforestation which occurs in comparable areas nearby, or the deforestation which might occur if the forest was not under protection.

How do you know what deforestation might otherwise occur?

That is a matter of judgment. Under REDD+ and similar schemes, certification experts take account of what deforestation—legal and otherwise—is taking place in a given region, and forest owners can be awarded carbon credits if they agree to keep more trees standing than is the average in that area.

So the same people who cut down the forest get money for leaving some bits standing. Doesn’t this give forest owners or loggers an incentive to hold forests to ransom?

Arguably, yes. However, they are often right in their claims that forests would be in danger without legalized logging and carbon credit schemes—forests in many parts of the world enjoy few protections, as even when they are legally off-limits to loggers, in practice governance is often poor and violations frequent. At least certification schemes require monitoring and frequent evaluation, so companies can more easily be held to account.

Won’t loggers just move to the next bit of forest, that isn’t covered by carbon credits?

They could indeed do that—in the jargon, this is known as “carbon leakage.” Carbon offsetters try to avoid that by taking the wider region into account.

The whole system sounds full of holes.

Even enthusiasts for carbon offsetting do not claim the system is ideal. Some offsetters draw the line at avoided deforestation: the Gold Standard offsetting program, for instance, backed by green groups including the World Wildlife Foundation, does not issue credits for avoided deforestation projects because of the concerns above.

But in the absence of a global system that rewards forested nations for preserving their forests, and monitors their success in doing so, offsetting does provide a source of income and protection to some areas, and at least some form of monitoring and accountability to ensure that companies are sticking to their commitments.

What are the long-term solutions?

Carbon offsets can only ever be a band-aid, not a cure. To keep the world’s forests standing, at least $100 billion needs to flow to heavily forested developing countries each year.

Global efforts are needed to encourage nations to keep their forests standing, alongside political and public pressure on recalcitrant governments. At the postponed UN climate summit, COP26, to be held this autumn in Glasgow, Scotland, governments will have to set out national plans for meeting the 2015 Paris agreement. That may be the last chance for a concerted plan to save the world’s remaining tropical forests—and the British hosts will have to prove they are up to that task.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: REDD, cap and trade, carbon credits, carbon footprint, carbon offsetting, carbon tax, climate change, climate crisis, deforestation, emissions, global warming, greenwashing

Topics: Climate Change