Biden should end the launch-on-warning option

By Frank von Hippel | June 22, 2021

Time exposure showing the tracks of the missiles’ six dummy warheads, white-hot from air friction, arriving 8,000 km down-range near Kwajalein Atoll in the Western Pacific. The domes in the foreground house tracking telescopes. As a part of the post-Cold War reductions, the Minuteman IIIs were downgraded to one warhead each. Credit: US Air Force photos from National Security Archive and US National Archive collections respectively. Public domain image.

Time exposure showing the tracks of the missiles’ six dummy warheads, white-hot from air friction, arriving 8,000 km down-range near Kwajalein Atoll in the Western Pacific. The domes in the foreground house tracking telescopes. As a part of the post-Cold War reductions, the Minuteman IIIs were downgraded to one warhead each. Credit: US Air Force photos from National Security Archive and US National Archive collections respectively. Public domain image.

Both Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama came into office proposing to take US intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) off their “hair-trigger alert” status, which keeps them ready at all times to launch within minutes. The time is so short for a president to have to decide to launch in response to Strategic Command’s assessment of an incoming attack that President Bush reportedly complained it might not even be enough time for him to get off the “crapper.”

While in office, Bush failed to act on his concerns. President Obama pursued the issue but retreated in the face of opposition from Strategic Command. The most he could get in the 2013 Nuclear Employment Strategy of the United States was a promise to look into the matter:

Recognizing the significantly diminished possibility of a disarming surprise nuclear attack, the guidance directs [the Defense Department] to examine further options to reduce the role of Launch Under Attack plays in US planning, while retaining the ability to Launch Under Attack if directed.

Strategic Command prefers to use the term “launch under attack” because a launch would only occur if there were high confidence in the warning that an actual attack was on its way. Strategic Command has never explained how high such confidence would need to be for a decision capable of causing directly and indirectly the deaths of at least a hundred million humans.

Launch on warning is controversial for two reasons: First, history has shown that false warnings do occur due to equipment failure and human error, and today there is the additional danger of hackers. Second, a launch-on-warning posture is indistinguishable from being constantly poised to mount a first strike, which pressures Russia and China to put their missiles on hair trigger as well. The United States would be on the receiving end for any mistaken launch one of them makes.

President Biden has indicated he does not support first use of US nuclear weapons. He should end the launch-on-warning option and the danger it entails of an unintended nuclear Armageddon. He could order Strategic Command to plan the US nuclear posture on the assumption that he will not launch on warning. US nuclear planners would have to assume a delayed response and revise their contingency plans accordingly.

Fifty years on hair trigger. The launch-on-warning option has been debated within the US government since the Kennedy Administration but was adopted during the 1970s. In the 1980s, because of his concern about accidental nuclear war, President Reagan wanted to negotiate an agreement with the Soviet Union to eliminate ballistic missiles in favor of bombers, which can be recalled after launch.

Today, US Strategic Command keeps launch ready virtually all of its 400 single-warhead Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) plus about as many warheads on its submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) at sea. It wants to be able to launch the ICBMs before they and the US nuclear command and control system can be partially destroyed by an incoming Russian attack. This posture also puts the United States in a position to be able to quickly implement a “damage-limiting” strike on Russia’s or China’s nuclear forces in case they appear to be preparing to launch. Russia is believed to have a large fraction of its ballistic missiles in a similar “hair-trigger” posture, and the US Department of Defense believes China is preparing to place its silo-based ICBMs into such a posture.

The longest flight time of an ICBM attacking the US would be about 30 minutes, and the flight time from an offshore submarine to Washington could be as little as 10 minutes. Subtracting the times required to determine the targets of the incoming missiles and to implement any response leaves at most 10 minutes for a presidential decision.

Launch on warning is described by US nuclear policy makers as only an “option.” In 1998, however, Gen. Lee Butler, the first Commander in Chief of Strategic Command (1992-94), warned that if Strategic Command became convinced that a nuclear attack on the United States was on its way, the president would be pressured to launch.

In an interview with Jonathan Schell, Butler described Strategic Command as having “built a construct that powerfully biased the president’s decision process toward launch before the arrival of the first enemy warhead. And at that point, all the elements, all the nuances of limited response just went out the window. The consequences of deterrence built on massive arsenals made up of a triad of forces now simply ensured that neither nation would survive the ensuing holocaust.”

Bruce Blair, who discussed this problem with Butler and some of Butler’s successors, reported that “jamming” is the term used to describe the process of pressing an inadequately prepared president to launch.

A strategy of “damage limitation.” Launch on warning is not required to deter a nuclear first strike by Russia on the United States. A delayed retaliation by US ballistic missile submarines could by itself totally devastate Russia or any other adversary.

Launching quickly is required, however, for what Strategic Command and its predecessors have as far back as 1964 considered their primary mission: “damage limitation.” Damage limitation is a neutral way to describe plans to preemptively destroy as much of the adversary’s nuclear arsenal as possible before it can be used.

Until his untimely death in July 2020, Bruce Blair, more than any other outsider, enjoyed the confidence of former leaders of the United States and Russian strategic commands. Blair provided the most detailed publicly available information on US nuclear-war planning, including in 2018 when he reported that:

[US] strategic war plans … designate an estimated 1,425 total primary and secondary aimpoints in [Russia and China]. There are 975 in Russia spread across the three categories: 525 for nuclear and other WMD [weapon-of-mass-destruction facilities], 250 for [conventional] war-sustaining industry, and 200 for leadership. The Chinese target set is approximately 50 percent smaller: 450 total aimpoints, including 140 for nuclear and other WMD, 250 for war-sustaining industry, and 60 for leadership. Many targets in all three categories are located in densely populated Russian and Chinese urban areas; 100 such aimpoints dot the greater Moscow landscape alone.

Russia presumably has a similar set of targets in the United States.

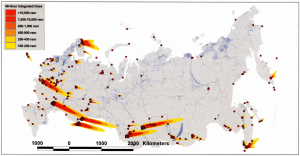

Among the targets of an attack on Russia’s nuclear-weapons infrastructure (Figure 1) would be nuclear command posts, communication links, bomber and submarine bases, nuclear weapon laboratories, and warhead assembly facilities in and near populated areas. Even for isolated ICBM silo fields, lethal radioactive fallout from numerous ground bursts could extend hundreds of miles downwind and, depending on which way the wind was blowing, could bring death to large cities. The result of all these nuclear detonations would be millions of “collateral” civilian fatalities.

If Russia had, in fact, already launched a massive strike on the United States, many of its missile silos, bomber bases, and submarine bases would be empty by the time retaliatory US ballistic missile warheads arrived. A US damage-limitation attack therefore would be much more effective if it could be launched preemptively on reliable intelligence of an imminent Russian attack.

The same logic would apply on the Russian side.

A full-out nuclear war between the United States and Russia would result directly in more than 100 million deaths in the United States, Russia, and Western Europe, where the United States, France, and the United Kingdom have nuclear weapons that threaten Russia. A much larger number of deaths could be caused indirectly by the collapse of national and global trade and the war’s potentially multiyear impacts on the global ozone layer and climate and therefore on food crops.

Too many false warnings. In the midst of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, a training tape was inserted in the computer of an improvised early-warning radar pointed toward Cuba at the same time that the radar detected a satellite passing overhead, confusing the operators and causing them to report an incoming missile.

In 1980, the Senate Armed Services Committee revealed that, during the previous two years, the US early-warning system had produced three serious false warnings of incoming Soviet attacks.

One was due to a technician loading into a Strategic Air Command computer a tape displaying a simulated Soviet nuclear attack. The other two were due to the failure of a computer chip in the early-warning system. To show that the warning circuit was working, the chip was programmed to transmit regularly “0000” for the number of incoming missiles but began including random twos as well.

Blair has reported that, in both cases, it took technicians eight minutes to determine that no warning signals were coming from the early-warning systems. This exceeded the three-minute limit required for such a determination and this delay “got [the crews manning the early-warning center] fired on the spot.” What would have happened had the crews followed protocol and reported back at three minutes that they had been unable to determine that the warnings were false?

Today, as Blair also pointed out, the communications from the early-warning sensors could be hacked. That might delay a determination of falsity beyond the president’s time window for a decision to launch on warning.

On the Soviet side, in September 1983, at a time of high tension between the United States and Soviet Union, an early-warning satellite misidentified the reflections of the sun off clouds over the northern US Great Plains as the exhaust plumes of five US Minuteman missiles emerging from the clouds. Lt. Col. Stanislaus Petrov was monitoring the satellite’s signals but delayed declaring an attack. He was not punished but was interrogated repeatedly about why he had not followed the prescribed procedures. Thirty years later, when Petrov was a lonely, grumpy retiree and widower, a documentary was made of his story, The Man Who Saved the World.

All the near misses that we know about happened during the Cold War, but the danger has not gone away. Tensions are rising again—this time with China as well as Russia. Indeed, the role of Taiwan as a potential nuclear trigger point in the developing US-China Cold War seems eerily reminiscent to that of West Berlin in the US-Soviet Cold War. And the added danger of hacking into the command-and-control systems is very worrisome.

Nonsensical arguments for launch on warning in the name of deterrence. In 2018, Congress instructed the Defense Department to “contract with a federally funded research and development center to conduct a study on the potential benefits and risks of options to increase the time the President has to make a decision regarding the employment of nuclear weapons.”

The Defense Department selected the Institute for Defense Analyses, which produced a report that appears to reflect Strategic Command’s views. It is therefore worth quoting the report in order to understand those views.

The authors of the report acknowledged the danger of mistaken launch. They also noted the incentive to launch on warning because of the vulnerability of the US nuclear command, communication, and control system. They wrote:

If a president feared that the [nuclear command, communication, and control] system was fragile, he or she might feel pressure to order nuclear strikes before the system degrades, particularly in a situation where a president thought that he or she might not survive.

The authors nevertheless argued against “de-alerting” US ICBMs because of the value of the launch-on-warning option as a deterrent to a Russian first strike.

If Russia were confident that it will be able to destroy US ICBMs on the ground, along with fixed bomber, [nuclear-capable] fighter-bomber, and SSBN [ballistic missile nuclear submarine] bases, it would be more optimistic about its chances of leaving the United States with a small nuclear force after the attack and no choice but to capitulate…

Before conducting a large-scale nuclear strike on the United States, Russia would likely require confidence that it could convince US leaders to back down, rather than comprehensively retaliate against Russia. However, if Russia knows that the US president has minutes to contemplate ordering a nuclear strike, potentially with hundreds of nuclear weapons, the possibility of an escalatory US response would make it less likely to risk a disarming first strike.

The idea that Russia would be tempted to mount an attack on US nuclear forces in the belief that the US might have “no choice but to capitulate,” when the US would be left with at least eight ballistic missile submarines at sea, carrying a total of about 700 warheads with yields equivalent to four to 12 Hiroshimas each, is, of course, nonsense.

The vulnerability of the US nuclear command, control and communication system is also overstated. The extended survivability of hundreds of nuclear warheads on ballistic-missile submarines at sea would guarantee that a delayed but still devastating US retaliation would be possible for at least several months and up to years after an attack on US command and control. No adversary could be confident that communications between a survivor in the US presidential line of succession and the surviving US ballistic-missile submarines could not be restored within that time. Nor could it know that the US president had not delegated launch authority to the commanders of US ballistic submarines should they be cut off from the US nuclear command and control system. Russia itself has a “dead hand” system programmed for such a contingency.

A possible first step: Don’t rely on launch on warning. A first step to reduce the danger of mistaken launch on warning would be for President Biden to order Strategic Command to plan the US nuclear posture on the basis of the assumption that he would not launch on warning. Launch on warning would still be physically possible, with whatever deterrence benefits that would stem therefrom, but US nuclear planners would have to assume a delayed response and revise their contingency plans accordingly.

I have been told by former insiders that, if it were given such instructions, Strategic Command could be much less reluctant to give up the ICBM force. Former Secretary of Defense Perry has been recommending doing so for some years. The total number of deployed warheads could be maintained by deploying an additional 400 warheads to US ballistic-missile submarines whose missiles are designed to carry up to eight warheads each but, due to New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) limits, currently carry about half that number on average.

The Defense Department’s 2013 Nuclear Employment Strategy of the United States stated, however, that the United States could “maintain a strong and credible strategic deterrent while safely pursuing up to a one-third reduction in deployed nuclear weapons from the level established in the New START Treaty.”

Of course, Strategic Command and Congress would prefer that such a reduction be done bilaterally with Russia.

In short, Strategic Command could get rid of launch on warning and the ICBMs at the same time. Eliminating launch on warning would significantly reduce the probability of blundering into a civilization-ending nuclear war by mistake. To err is human. To start a nuclear war would be unforgivable.

Additional reading

Bruce G. Blair, “Loose cannons: The president and US nuclear posture,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Volume 76(1), 2020, https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2019.1701279.

Frank N. von Hippel, “The United States would be more secure without new intercontinental ballistic missiles,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 11 February 2021, https://thebulletin.org/2021/02/the-united-states-would-be-more-secure-without-new-intercontinental-ballistic-missiles/

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: ICBM, launch on warning, nuclear risk, nuclear weapons

Topics: Analysis, Nuclear Risk, Nuclear Weapons, Opinion

Great article. It should be noted that while the US and Russia have Launch on Warning, China does not. In fact it separates the warheads from the launch vehicles so that accidental firing of a nuclear weapon cannot occur. With its No First Strike stance and its refusal so far to institute Launch On Warning, China is in fact a leader in the nuclear disarmament movement by what it does, not simply in what it says. But as the author acknowledges quite rightly, the US is putting ever greater pressure on China to institute Launch On Warning with its increased… Read more »

I am amazed by the confidence the anti-nuclear crowd has in their ability to accurately discern the psychology of foreign adversaries and to state so matter-of-factly what will and won’t deter. How can one be so sure that the decimation of ICBM’s, bombers, and as much as 2/3 of our SSBN’s (in maintenance or deployment work-ups) would not be perceived by a malign actor as an advantage? Why wouldn’t a preemptive counterforce strike that leaves the attacker with a substantial arsenal in reserve to deter our remaining SSBN’s retaliatory strike be considered an option? Would Biden follow through on such… Read more »