Why scientists should respond to Russia’s criminalizing of a US educational exchange

By Susan D’Agostino | July 22, 2021

Smolny College Commencement, 2019. Smolny College—the first liberal arts program in Russia—was founded as a dual-degree program between Bard College in the United States and St. Petersburg University in Russia. Last month, the Russian State Prosecutor’s Office labeled Bard College “undesirable,” which criminalized Bard’s decades-long partnership with St. Petersburg University. Photo credit: Bard College. Used with permission.

Smolny College Commencement, 2019. Smolny College—the first liberal arts program in Russia—was founded as a dual-degree program between Bard College in the United States and St. Petersburg University in Russia. Last month, the Russian State Prosecutor’s Office labeled Bard College “undesirable,” which criminalized Bard’s decades-long partnership with St. Petersburg University. Photo credit: Bard College. Used with permission.

The Russian State Prosecutor’s Office last month labeled Bard College “undesirable,” claiming that its activities “pose a threat to the foundations of the constitutional order and security of the Russian Federation.” The decision has criminalized and ended Bard’s decades-long partnership with St. Petersburg University which, among other accomplishments, created Smolny College—the first liberal arts college in Russia. By law, anyone in Russia found guilty of associating with an “undesirable” organization may face significant fines and up to six years in prison.

“The decision to ban Bard College demonstrates the Russian state’s continual censorship of education and civil society,” said Polina Sadovskaya, PEN America’s Eurasia program director. “The blacklisting of educational institutions violates the rights of citizens to pursue education and knowledge and restricts freedom of expression.”

Bard College is the 35th organization to be labeled “undesirable,” though the first US college or university. Many worry that the move has set a precedent for targeting other Western higher education institutions.

“In other words, this isn’t a small deal. This is a very, very big deal, and it will cause every western university that has any partnerships with Russia to step back and think,” Sam Greene, Russia Institute director and professor of Russian politics at Kings College London, wrote.

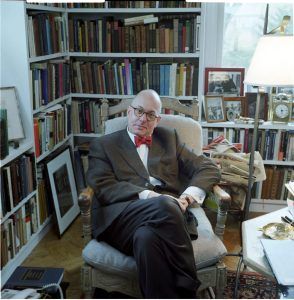

I recently caught up with Bard College president and Smolny College co-founder Leon Botstein to discuss recent events, the need for acts of solidarity among scholars worldwide, and the legacy of American pianist Van Cliburn’s 1958 Tchaikovsky Competition win in Moscow during the height of the Cold War. Botstein is unusually qualified to speak about the latter; since 1992, he has served as the music director and principal conductor of the American Symphony Orchestra. As a conductor, Botstein is known for curating music around ideas from history, visual arts, literature—and even politics and science.

“When it comes to ambitious, fearless orchestral programming there is Leon Botstein … and then there is everyone else,” Steve Smith wrote in the New York Times.

As a Bard College alumna living in New York in the 1990s, I witnessed Botstein’s musical gifts during many of his concerts at Carnegie Hall in New York City and on Bard’s pastoral Hudson River Valley campus. What follows is an edited and condensed transcript of our conversation that speaks to the value of educational and musical collaborations in people-to-people diplomacy.

Susan D’Agostino: Can you offer context for Russia’s decision to deem Bard an “undesirable” organization?

Leon Botstein: This is the first time this law has been used against an accredited American university. This is not a small matter. This is an arbitrary and unjustified act on the part of the Russian government. We’ve protested with the State Department, and the State Department now has it on its agenda. We hope that it can be reversed.

The reason for it is political. As in the United States, there is tremendous pressure from a nationalist far right in Russia. The Western press likes to talk about [Russian lawyer and anticorruption activist Alexei] Navalny and the liberal opposition, let’s call it, in Russia. But that liberal opposition appears to have no real traction in Russia. The real traction—it’s hard for us to imagine this reading the Western press—is that Vladimir Putin has a right wing which finds his brand of leadership insufficiently national, aggressive, and anti-Western.

In Russia, there’s been always a tension symbolized as the tension between Moscow and St. Petersburg—between a Russia that has a sense of itself in a non-Western, Eastern, right, religious, spiritual, and cultural direction, and then there is the legacy of Peter the Great, that opened a window to the West where Russia is part of Europe, in the largest sense of the word.

This tension, which has existed for a long time, exists today. Especially after the fall of the Soviet Union, there has been a romance with a certain account of history, which glorifies the 18th century Russian empire of Catherine the Great and the 20th century empire of Stalin: Russia as a world power that sees the West as degenerate, as negative, and as a threat.

In this very traditional historical context, Bard has been pegged because of our association with the Open Society Foundation and [Hungarian-born American billionaire investor and philanthropist] George Soros.

Susan D’Agostino: You’re a board member of the Open Society Foundation. Can you share insight on the foundation’s engagement in higher education in general and Bard’s program in particular?

Leon Botstein: Of the top 10 universities in England, nine of them have received philanthropic support from the Open Society Foundation, which is no different than getting philanthropic support from Rockefeller or Carnegie or let alone the National Institutes of Health or the National Science Foundation. And in America, of the top 40 ranked institutions of higher education, 33 of them have received funds from the same institution. In addition, the Open Society Foundation and George Soros were responsible, right after the fall of communism, for a $100 million investment in Russian science to support the crumbling infrastructure in the transition from the Soviet period to the modern period.

But there has been an understandable, open quarrel between Putin and the Open Society Foundation’s principles, which are about an open society and is firmly against autocracies of all kinds. The Open Society Foundation was declared “undesirable” in 2015. It was a matter of public record that the Open Society Foundation invested in the starting of Smolny 25 years ago. But since 2015, no Open Society or Soros-related money has gone to Smolny.

As you know—you’re an alumna—Bard is not a single-donor institution. We are dependent on both tuition income and private philanthropy, of which Mr. Soros is an important part.

Susan D’Agostino: Is this kind of philanthropic behavior well understood outside of the United States?

Leon Botstein: In the Russian context, the notion of someone giving money without exercising control is inconceivable. The habit of private philanthropy which developed in the United States is quite unusual. American universities and research institutions have achieved a remarkable level of autonomy, despite philanthropic support by individuals and NGOs. And that autonomy also extends to research grants from the government.

It’s inconceivable in the Russian space to persuade someone that, if you took a grant from someone, you’re not beholden to that person, to that person’s ideological beliefs. It’s simply inconceivable that the autonomy of a university can be preserved in the face of its need for economic support.

Now, American institutions are imperfect in that regard. But multiple-funded institutions like Bard have maintained a great deal of autonomy. We’re not a political institution. We have worked well under the era of Putin. Our primary objective is pedagogical in creating a spirit of critical inquiry. Our major emphasis is the arts and humanities. We are in the culture and arts world. We’re not in the political world. We have absolutely obeyed every Russian law. We’ve been good citizens, and we’ve had a huge success. We’re very popular among students and faculty.

However, in the political context of parliamentary elections in Russia, we became a convenient target for the far right. The conspiracy theories that revolve around the mythologizing of George Soros are among the oldest and most successful political conspiracy theories in history. The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which posits the secret conspiracy of Jewish financiers controlling the economics of the world, is a Russian forgery from the early 20th century. And this fiction is a major product of deep-seeded Russian antisemitism. And as in Hungary, the figure of George Soros, now 91, as a puppet master of the world is an extremely successful myth, especially when it’s put on social media.

Susan D’Agostino: Are you concerned that Russia’s “undesirable” designation for Bard has set a precedent for targeting other Western universities in the future?

Leon Botstein: American academics and scientists need to be much more outraged by this than they have been.

My argument—not my argument, but my appeal—to Secretary of State Blinken and to President Biden, is that for an American institution of our stature to be declared “undesirable” without evidence, without proof, of essentially operating in a treasonous way against the Russian state is worse than the Cold War. If I were a scientist or scholar in some joint program, to let this go is to tacitly approve of this kind of arbitrary shutting down. Somebody, somewhere, made a mistake—a mistake that can be undone. Mistakes happen, but for it to be ignored would be a terrible precedent.

Susan D’Agostino: How can it be undone?

Leon Botstein: What you need is the most prominent scientists—the kinds of figures and institutions that the Russians do want to cooperate. It would mean the equivalent of Albert Einstein or [American physicist and 1969 Nobel Prize recipient] Murray Gell-Mann saying they’re going to break off their connections unless this is reversed, basically an act of solidarity among scientists and artists and intellectuals.

I do hope that the diplomacy will work, but people need to understand that this is not so simple a matter, let’s say, of demonizing a government. Just as our government is caught in this extremely polarized political situation in which we find ourselves in the United States, there’s a parallel phenomenon there. As nationalism and this kind of very virulent, highly-militarized form of patriotism exists in the United States, it exists in Russia. And there’s a lot of popular support for it. The government is at its peril to ignore it.

We have our allies and friends in Russia who believe they are Russian patriots but believe in a Russia that is different from the one envisaged by this far right.

Susan D’Agostino: What happens if that act of solidarity among scholars does not materialize?

Leon Botstein: The worst signal that they’re now waiting for, in my view, is if they successfully say, “It was a great PR victory for us to assuage the far-right, and nobody cared.”

In other words, you gun down a child on the street and since it wasn’t an “important” person, people forget about the death of this child. We’re not MIT. We’re not the University of California at Berkeley. We happen to be the largest Russian-American collaboration, but still, why should anybody care?

We were supposed to give dual-degrees this spring, and the Russians shredded the degrees. We have a New York State Regents-accredited degree in higher education. I don’t think American academics can simply watch the shredding of that with impunity. It’d be one thing if we were tried and found guilty in any kind of court of law. We’re not guilty of anything. People need to say to the [Russian] government, “I understand why you did it, but it needs to be reversed.”

Susan D’Agostino: If I’ve calculated correctly, you were 11 years old when Van Cliburn won the 1958 Tchaikovsky competition. Do you remember that moment?

Leon Botstein: I remember not only Van Cliburn, but I remember the debut of Rostropovich in the United States as if it were yesterday. I remember when the New York Philharmonic went with Leonard Bernstein to Russia. I remember when Glenn Gould, the Canadian pianist, made his spectacular debut in Moscow. I met my mother’s first cousin who was in the Moscow Chamber Orchestra under Rudolf Barshai on their first visit to the US.

My great-great-great-grandfather was the chief rabbi of Moscow at the turn of the century. My grandmother was born in Moscow, and my mother lived there until her ninth birthday. I also ran the American Russian Young Artists Orchestra together with [Russian conductor Valery ] Gergiev. I have a long connection with Russian music and musicians. We’ve also premiered a lot of Russian music and done a lot of Russian music in the United States; we did the first modern production, of one of the great Russian operas, Taneyev’s Oresteia, here in the United States.

The Van Cliburn competition winning was a big event in my childhood. A big event.

Susan D’Agostino: Does it carry significance for you now?

Leon Botstein: Yes, it’s totally relevant. If we are in a kind of new-style Cold War with the Russian government, it’s all the more important that this kind of educational and cultural exchange remain and that it be supported, even against populist sentiments by the governments. I believe this is solvable. It’s in the long-term interests of both the Putin government and the Biden government not to have this kind of thing happen.

Susan D’Agostino: My sense is that musical collaborations and educational exchanges are about people learning from and with each other rather than simply about each other. Why is this distinction so important?

Leon Botstein: The answer lies in the most remarkable feature of this splendid program [at Smolny College]. Unlike [other] American university programs abroad, this liberal arts four-year degree was delivered in the Russian language. There is no learning about another culture without acquiring its language. The language is the key to unlock the door.

[Bard’s dual-degree program at Smolny] is not like Harvard University or Stanford University abroad where the programs are conducted for American students in a foreign country. No, no, no. This is for Russian students—a liberal arts program in Russia. The Americans that went over there had to either learn or command the Russian language.

This program was rooted in and designed by our Russian colleagues, foremost of them was the former long-time [St. Petersburg University] rector, Lyudmila Verbitskaya—a very prominent scholar and administrator. Actually, Putin worked for her under the Soviet period in the university. She was a Russian philologist—[a scholar who studies language in oral or written historical sources]. Her commitment to the place of Russia through the world was through the language. The deal we brokered, which took her aback when we started it was, “We want to do this program, not in English, but in Russian.”

Susan D’Agostino: What moved you to craft such a singular US-Russian program?

Leon Botstein: Having grown up in the Cold War, I never believed that I would ever see the places I had read about in the novels of Dostoevsky or Tolstoy or the short stories or poetry of Pushkin. Places like St. Petersburg’s Kazan Cathedral, which has a scene in [Nikolai] Gogol’s The Nose, I saw in my mind through literature as a young person. It was magical to be able to go there, finally, at the period of perestroika [restructuring] and then after the fall of communism.

And so, of course you can learn about—as we do about history—things we cannot see and touch ourselves. But the people-to-people diplomacy, especially with modern technology, remains ever more dependent on language. The center of the Smolny exchange was a mutual regard for the Russian language.

Susan D’Agostino: You’ve offered global, national, political, economic, and social context, but what has this meant to you?

Leon Botstein: Oh, for me, this is a tragedy. I grew up in a home in which Russian was a present living language. It was my mother and father’s first language. It was the language of my grandparents with whom I spoke growing up. My engagement as a person with Russian literature, music, and history is based in my earliest childhood. There is no program that [Bard had] with which I had a deeper personal relationship and more friends and colleagues in music and in higher education than in Russia. For me, this is a tragedy—more than 25 years of work and efforts. This is not some program to which I have a detached personal connection. Not at all. Someone asked me whether I thought this was dead. I said, “No, it’s in a coma, and it has to come out of the coma.” That’s our objective. Even in the depths of the Cold War, intellectual and cultural exchange continued.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Bard College, Cold War, Leon Botstein, Putin, Russia, US-Russia relations, US–Russian relations

Topics: Interviews, Nuclear Risk, Opinion