Biden should guide missile defense his own way

By Ivanka Barzashka | September 9, 2021

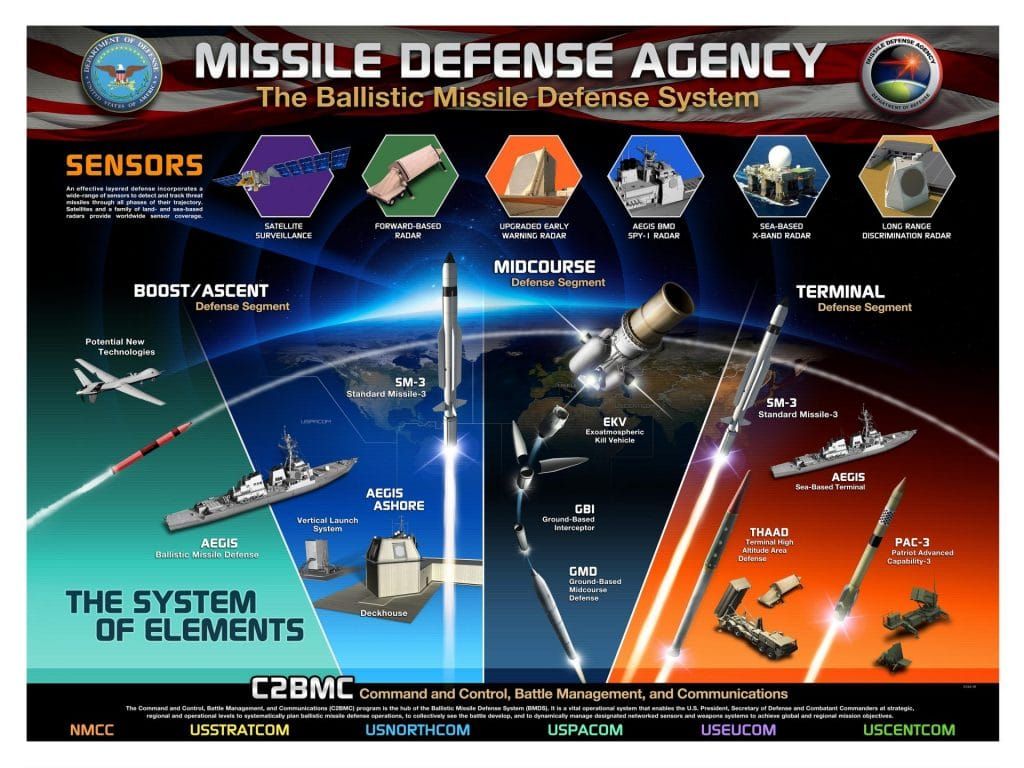

A Defense Department graphic depicts the Ballistic Missile Defense System architecture. Credit: US Defense Department.

A Defense Department graphic depicts the Ballistic Missile Defense System architecture. Credit: US Defense Department.

The Biden administration has begun a review of US missile defense policy. The review is part of a broader effort to align defense strategy and posture with the president’s commitment to lead through diplomacy, repair alliances, and rebuild the American economy.

In 2019, Trump declared the “beginning of a new era” in America’s missile defense program. He envisioned an “unrivaled and unmatched” missile defense system with a “simple goal” to defend against “every type of missile attack against any American target.” This decision reversed longstanding US policy to build defenses against emerging nuclear missile threats from North Korea and Iran but not against established nuclear powers. While Trump’s ambitions did not produce immediate changes to US posture and capabilities, he made one of the biggest—and quietest—changes to US declaratory policy in the last two decades.

This quiet change is facing stormy waters. Moscow and Beijing have long claimed US global missile defense plans, including a NATO system in Europe and defenses in East Asia, will eventually target Russia and China, and thus threaten strategic stability. This year, over 60 American national security experts agreed: America’s missile defense system has “accelerated an arms race with Russia and China, leading both adversaries to expand their offensive nuclear weapons programs to counter US missile defenses.” In an open letter, they urged President Joe Biden to “walk us back from the brink now.”

Biden now faces a choice on missile defense policy: Does he embrace Trump’s “simple goal” to defend against “every type of missile attack against any American target”? Or does he revert to the policies of the Obama and George W. Bush administrations to build defenses only against limited nuclear strikes from North Korea and Iran and rely on deterrence and diplomacy against major nuclear powers like Russia and China?

The answer lies not in partisan debates but in new strategic thinking on the roles of missile defense in a changed security environment.

For two decades, US leaders worried that North Korea could blackmail the United States and its East Asian allies with limited nuclear attacks using ballistic missiles that would eventually have the range to reach the American homeland. They were concerned that Iran, if it decided to build nuclear weapons, could similarly threaten Europe. The threat of American nuclear retaliation alone would not credibly deter rogue states, so the United States needed the capability to defend its homeland, forces, and allies from such nuclear attacks.

The Bush and Obama administrations sought “collaborative and cooperative relationships” with Russia and China. They assured Moscow and Beijing—who vocally opposed US missile defense—that the system was not aimed against them and would not threaten strategic stability. This assertion was backed by scientific facts. Experts publicly demonstrated that US defenses could intercept North Korean and Iranian missiles but not Russian ones.

The Trump administration identified China and Russia as “potential adversaries,” alongside North Korea and Iran. To counter these adversaries, the United States envisioned an “unrivaled and unmatched” missile defense system that would deal with a diverse range of ballistic, cruise, and hypersonic missiles, which can carry nuclear or conventional warheads. Missile defense was part of a new comprehensive approach to integrate “offensive and defensive capabilities for deterrence” and protection, as part of an overarching US strategy to “out-compete” and “out-innovate” rivals.

However, Trump’s ambitions did not amount to significant real changes to US strategic posture. It relied on expensive and ambitious new technologies—like space sensors and weapons—some of which the Pentagon cancelled and Congress never properly funded. The Congressional Budget Office estimated expansions and new systems “could cost tens or hundreds of billions of dollars.”

Yet Trump’s “simple” goal confirmed Moscow’s worst fears that America’s missile defense project would eventually target Russia. It further justified Russia’s military modernization and efforts to build a joint defense system with China. It confused European allies who had signed up for a joint system focused on ballistic missile threats “emanating from outside the Euro-Atlantic area.”

Biden can neither fully embrace the Trump policy nor revert to preceding approaches. How does the United States go forward from here?

Biden should accept Trump’s view that US missile defense has new strategic roles against major powers. Biden’s missile defense review, like the 2019 version, should start with a threat assessment that extends beyond ballistic missiles to include adversaries’ aerospace offense and defense capabilities. It should similarly explicitly acknowledge that layered defenses have roles in nuclear, as well as conventional conflicts.

However, Biden should reject the Trump administration’s assertion that all “missile defenses are stabilizing.” It should similarly repeal an ideological policy that seeks “to continuously” strengthen and expand missile defense, regardless of circumstances. Biden’s new policy should recognize that, to achieve strategic objectives effectively and efficiently, the United States may require more or less missile defense capabilities or a different approach altogether, such as arms control.

Here, Biden’s team needs new thinking on how missile defense affects the long-term balance of strategic advantage in peacetime, crisis, and war with different opponents. Is the Cold War concept of strategic stability useful for framing US relations with Russia and China? If so, how should it account for new technologies like hypersonic cruise missiles, warfighting domains like cyber and space, and linkages between nuclear and conventional conflicts? Are there tradeoffs between efforts to reduce nuclear risks from major powers versus regional actors? What role should an integrated, layered missile defense system play in a US theory of victory for regional conventional wars under the nuclear shadow? How should US defense posture be sized to avoid arms races and crisis instabilities?

To explore new arms control options, Biden should break with the policies of Bush, Obama, and Trump. Like Nixon, he should be prepared to negotiate with rivals limits on US missile defense ambitions in the interests of national security and international stability.

Biden cannot reverse the new era in missile defense, which is marked by Trump’s words but ultimately defined by the new strategic problem of major power competition. However, Biden’s team can develop a clear and balanced approach to missile defense that aligns US and allied capabilities with the president’s promises to meet future challenges, and that grounds policy in “fact and science” and strategic thinking.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Biden, US nuclear policy, United States, missile, missile defense, nuclear policy

Topics: Nuclear Risk, Nuclear Weapons, Opinion

The fact that defense against ICBMs (not to mention the hypersonic cruise missiles) doesn’t and won’t ever work needs to be recognized.