The Australian submarine agreement: Turning nuclear cooperation upside down

By Ian J. Stewart | September 17, 2021

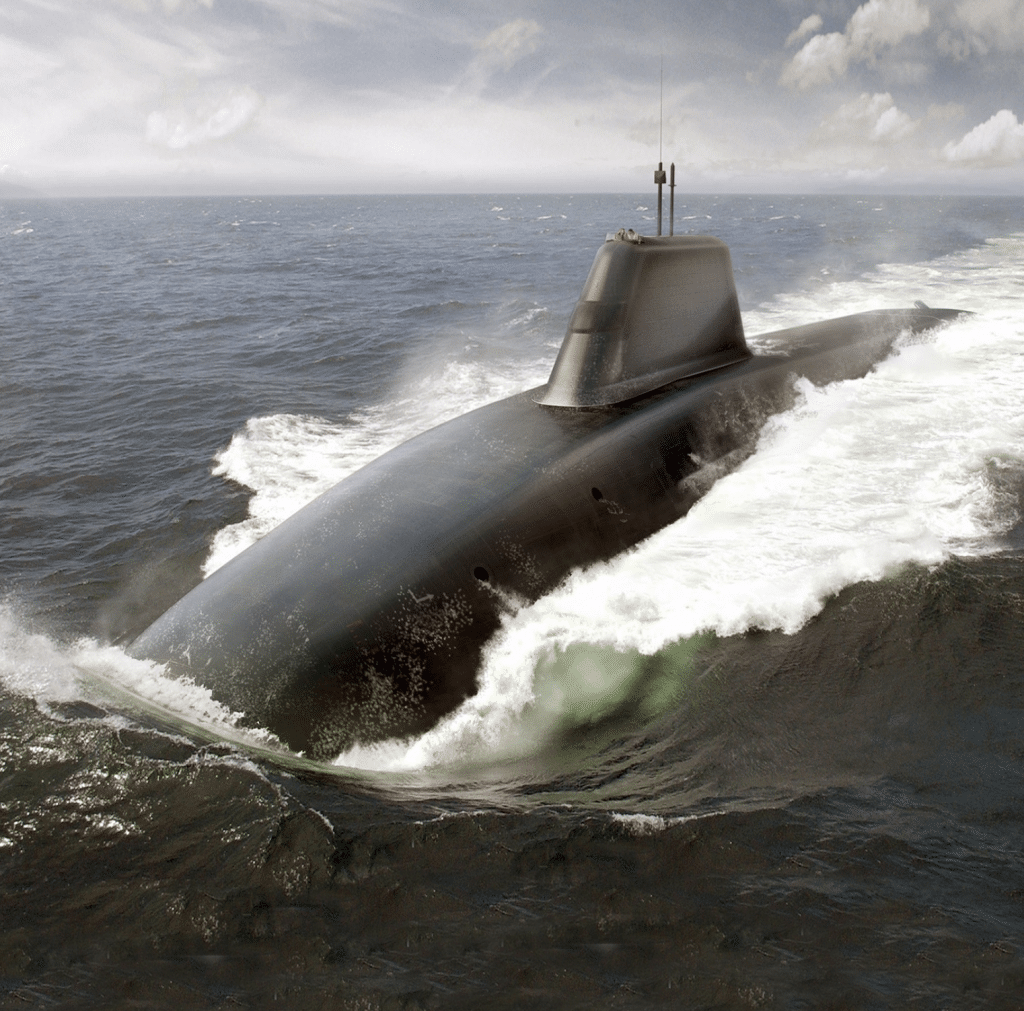

An illustration of the Dreadnought class of submarines to be built by a British alliance of entitities that includes Rolls Royce.

An illustration of the Dreadnought class of submarines to be built by a British alliance of entitities that includes Rolls Royce.

The UK and US have announced they will support Australia in development of a nuclear submarine fleet and will provide (conventionally armed) Tomahawk cruise missiles. This is one of those exceedingly rare and exceedingly significant announcements that come along only every decade or so. The announcement literally turns existing precedence and practice on their heads in order to extend traditionally northern hemisphere cooperation to Australia and bolster its role in countering an increasingly assertive China. While much is not yet known, some of the ramifications and implications of this development are discernable.

Before considering the announcement’s specific implications, it is worth reiterating how exceedingly rare and significant it is. Many in the nonproliferation and strategic studies field will draw a parallel between this announcement and the 2005 announcement that the United States would renew civil nuclear cooperation with India. The so-called AUKUS declaration, like the other, was made with the grand purpose of securing an additional strategic ally against the rising China. However, neatly associated with both is also an expectation that domestic industries will benefit from access to a new market.

The announcement itself is somewhat light in detail. It states that the UK and United States will work with Australia to identify the optimal path towards nuclear-powered submarines. A separate announcement revealed that Tomahawk cruise missiles would also be transferred. For tasks such as intelligence collection and antisubmarine warfare, nuclear submarines offer a unique combination of endurance, speed and stealth.

Anyone who has worked in governments or a large bureaucracy will understand how challenging it can be to reach a paradigm-shifting policy decision. In this announcement, the United States and UK are overturning decades of accepted practice to support the transfer of a strategic capability to another country. The decision is sure to irk China and accelerate the spiral towards a Cold War-style standoff, with renewed strategies of containment against the revisionist power. The initiative has also offended France, which had become closer to the UK and, to a lesser extent, the US on nuclear matters in the last decade or so.

The first obvious implication from the announcement is, in fact, its undercutting of France. France and Australia had entered a contract for the Australian production of a conventionally powered submarine. The cooperation under this arrangement was apparently dogged by practical troubles, which is understandable; submarine construction is difficult. However, the cooperation was viewed as a larger defense relationship that was a pathway to French significance in Asia. The Australian breakup with France is clearly not a happy one, with the French Embassy tweeting its contempt for how the announcement was made. On Friday, France announced it was recalling its ambassadors to the United States and Australia, calling the US-Australia agreement “unacceptable behavior between allies and partners.”

“The 🇺🇸 choice to exclude a 🇪🇺 ally and partner such as 🇫🇷 from a structuring partnership with Australia, at a time when we are facing unprecedented challenges in the Indo-Pacific region (…) shows a lack of coherence that 🇫🇷 can only note and regret.”https://t.co/ruGnJkQAWa

— Embassy of France in the U.S. (@franceintheus) September 16, 2021

A second implication is for the nonproliferation regime itself. Much like the announcement of the US-India deal, AUKUS is already dividing the international security community. Many nonproliferation practitioners call foul, on the basis that, on the face of it, the announcement appears to cut across several norms, agreed rules, and accepted practices. The cooperation may be used by non-nuclear weapons states as more ammunition in support of a narrative that the weapons states lack good faith in their commitments to disarmament.

The merits of this argument are limited, however, as the cooperation does not involve nuclear weapons and, as set out below, the safeguards precedence set could be positive. And it should be noted that, nonproliferation points aside, AUKUS is a relatively straightforward strategic step. Through a number of forums, the United States, UK, and Australia have been cooperating in countering the perceived threat caused by China’s rise. Additionally, as leading members of the so-called five eyes intelligence sharing community, all three countries are already well set up for interoperability in relation to strategic and intelligence topics. Indeed, such is the centrality of the five eyes community that on hearing such an announcement, one wonders why Canada is not a party. Canada did, after all, buy its somewhat beleaguered current submarines from the UK (one of which was said to have caught fire when moving from the UK to Canada). The exclusion of the fifth of the five eyes from AUKUS is altogether more straightforward; New Zealand is decidedly antinuclear in a way that causes tension with its other allies—tensions that are only likely to deepen with this cooperation.

A third implication involves precedence. There has been constraint in terms of naval nuclear reactor exports for many decades. However, several countries have been working to acquire naval nuclear reactors. Brazil is perhaps the first country that comes to mind. It will be argued by many that AUKUS reaffirms Brazil’s legitimacy in pursuing nuclear-powered submarines. The reality is that Brazil was moving forward with its program regardless of what nonproliferation practitioners had to say, so this may not be the most significant precedence. Instead, others will point to countries, such as Iran, that have long toyed with the idea of nuclear-powered submarines as yet another excuse to produce largely unneeded nuclear material.

Before concluding that this precedence is negative for the nonproliferation regime, more information is needed on exactly how AUKUS will move forward. Australia is not Iran or Brazil. It is accepted that countries in good standing with the nonproliferation regime have a right to use nuclear energy for non-weapon purposes (which includes use in submarines). There is potentially a strong argument to be made that a country like Australia—which has both an IAEA safeguards Additional Protocol in place and for which the IAEA has reached its “broader conclusion” that all nuclear material remained in peaceful activities (i.e. non-nuclear weapons purposes)—can credibly possess nuclear submarines without undermining the nonproliferation norm. Additionally, if done right, the cooperation can potentially lead to a valuable model on how to apply safeguards to submarines. Depending on whether the submarines will be designed to use low-enriched uranium or highly enriched uranium, the deal could also set a useful precedence, providing the US and UK experience with low-enriched uranium.

This argument is less strong with the reported planned transfers of Tomahawk cruise missiles. Semi-formal rules have been agreed to with regards to missile transfers under the Missile Technology Control Regime. These rules include a “strong presumption of denial” for transfers of category 1 systems, which includes cruise missiles with a range greater than 300 kilometers; the Tomahawk has a range of at least 1,000 miles. While the United States can legitimately say that a strong presumption of denial does not constitute an outright prohibition, from a practical perspective this transfer will lessen the norm against missile-related transfers. That norm is anyway under threat with, for example, the US agreeing that South Korea can develop missiles that exceed the MTCR category 1 thresholds, resulting in a South Korean missile test earlier this week. Ironically, the transfers to Australia are aimed at countering China, while China is among the countries that most readily flouts the missile control regime rules with its historically lax implementation of export controls and, resultingly, its supply of missile technology to countries such as Iran. China is not a member of the regime but has committed to adhere to it.

Finally, the announcement is likely to have particular significance for the UK’s nuclear program. The UK is struggling through a number of issues related to the revamping of its nuclear enterprise by replacing its submarines, missiles, and warheads. The program is beset with uncertainty about the future basing of the submarines, given the possibility of a Scottish move toward independence. And the program is struggling to keep its key industrial player alive. Rolls Royce, which manufactures the UK’s submarine reactors, also is a leading producer of aircraft engines and was heavily hit by the decline in air traffic caused by COVID. It is unclear how many of these challenges the UK hopes AUKUS can address, but the British government is almost certainly thinking about it as a means to bolster Rolls Royce. The United States by law and by practice is particularly protective of its reactor technology. As such, the prospect of an independently designed UK reactor being sold to Australia could check a number of boxes.

The agreement may have an additional casualty in UK/French nuclear cooperation. Given the gargantuan challenges the UK faced in recapitalizing its nuclear infrastructure, it reached a 50-year cooperation agreement with France in 2010 which resulted in an agreement to share some nuclear weapons support development facilities. The agreement was made with US blessing but did not extend to the sharing of nuclear weapon design information, which presently takes place only between the UK and US under the 1958 mutual defense agreement. Given France’s reaction to the AUKUS announcement, the UK is likely to have to navigate some stormy waters if its cooperation with France is to continue.

Although a particularly unsatisfying abbreviation, AUKUS carries great significance from multiple perspectives. With the United States placing so much emphasis on countering China, it seems unlikely that nonproliferation concerns will hold back this initiative at this point. Instead, attention will have to focus on how to develop this as a positive precedence for the nonproliferation regime, rather than a negative one.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: AUKUS, Australia, France, Rolls Royce, UK, United States, ambassadors recalled, naval reactors, nonproliferation, nuclear submarines

Topics: Nuclear Risk

“it seems unlikely that nonproliferation concerns will hold back this initiative at this point. Instead, attention will have to focus on how to develop this as a positive precedence for the nonproliferation regime, rather than a negative one.”

Love the sentiment but struggle to find the way to a positive non-pro outcome …

Any extension of nuclear capability is a step toward war, which we already have plenty of, thank you very much!

Atomic bombs are useless, and have never been used in combat since 1945. Nuclear-powered submarines on the other hand are a useful offensive weapon, as in the sinking of the General Belgrano in the Falklands/Malvinas war in 1982. Proliferation of nuclear submarines opens a frightful perspective. Australia is not Iran, for sure, but it has a maverick goverment right now, hellbent on destroying the world with fossil fuels, sabotaging the upcoming Glassgow COP. Nuclear subs are also a strong boost for civil nuclear power, and may explain why the UK is building the absurdly expensive Hinley Point C power station… Read more »

“France and Australia had entered a contract for the Australian production of a conventionally powered submarine. The cooperation under this arrangement was apparently dogged by practical troubles, which is understandable; submarine construction is difficult.” Australia isn’t just pulling out of the deal cold turkey. The decision was reached because the French conventional submarine technology wasn’t working out the way the Australian Navy had expected. After cost over runs up to this year costing the Australian tax payer AUD29.5 billion (the entire programme was projected to have cost AUD36.5 billion), with nothing to show for the expense, the contract was cancelled. … Read more »

Also Australia will also have to build a complete infrastructure to support nuclear submarines for harbour to supply, repair and training. Now the Americans will have a base in Australia for their own nuclear submarines that the Australians will have to pay the bill for. And you think that their F-35’s were expensive to buy and maintain?

Australia already has bases shared with the U.S.A, where U.S. military personnel work with Australian military personnel. Another issue is the infrastructure to support nuclear submarines will mean jobs for Australians. For Australia to maintain its non-proliferation stance, the Australian nuclear propelled submarines may use Thorium Molten Salt Reactors (MSRs). One enormous advantage in developing MSRs is they produce Uranium-233, which is practically useless for developing nuclear weapons because of its much shorter half-life, compared with Uranium-235. Another advantage of Thorium MSRs for Australia, is that Thorium can be harvested from the existing tailings in abandoned or operating Uranium mines;… Read more »

Australia is an island continent a long way from anybody else. In that context, nuclear submarines are the logical defense initiative–separate from any other consideration. It is what you would buy if your only goal was defending Australia against invasion..

14 trillion since 9/11, spent from 2001 to 2020, half of which went to private contractors, per a recent study, Brown university’s Costs of War project.

Is there any other motive driving decisions other than the profit motive?

A nuclear arms deal with Australia, where we put our nuke submarines there, where Australia builds a place for them. Money Money Money. This supersedes any philosophical point of the Bulletin, any ‘moral justice’ equation. Its the same reason Dillinger used, when asked why he robbed banks: “That’s where the money is.