Grappling with environmental risks in the fog of war

By Kristina Hook, Richard “Drew” Marcantonio | March 10, 2022

On March 12, in the April Brovary district of the Kyiv Region there was a fire in a warehouse for frozen products as a result of shelling. Credit: Official Twitter-page of Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ukraine.

On March 12, in the April Brovary district of the Kyiv Region there was a fire in a warehouse for frozen products as a result of shelling. Credit: Official Twitter-page of Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ukraine.

The military escalation and re-invasion of Ukraine by the Russian Federation has sparked a complex humanitarian crisis that worsens daily. On March 10, the United Nations confirmed at least 1,506 civilians have been killed or injured, while noting that these numbers are likely much higher. Even before Russia began its most recent assault on the country, the conflict with Russian-backed separatists in the Donbas region of Ukraine had claimed 14,000 lives and internally displaced more than 1.5 million people since 2014. Now, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees describes the situation in Ukraine as the fastest-growing refugee crisis since World War II. Evidence that the Russian Federation has intentionally targeted fleeing civilians and broken ceasefires suggests that the numbers of those killed and fleeing will only grow.

In this chaotic context of acute violence and kinetic warfare, the environmental disasters unfolding across Ukraine fall under the radar. One Ukrainian official tasked with coordinating the humanitarian response described environmental issues as beyond peoples’ ability to process. “Everyone is living under the constant threat of airstrikes,” she said. “It distracts a lot.” Another official at the Ukrainian Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources confirmed that while the besieged Ukrainian government is clear-eyed about the short- and long-term risks to human health from invading Russian forces, “people are much more worried about bullets and bombs flying through the air than they are particulate matter floating about or toxic chemicals emitted that may cause cancer. We don’t have such luxuries [to consider environmental risks] at the moment.”

But as the war and accompanying humanitarian crisis escalate, Ukrainian and international officials and scientists are increasingly concerned about emerging environmental hazards. Ukraine is heavily industrialized, dotted with chemical facilities and nuclear power plants, often in close proximity to commercial and residential areas. Many toxic and irradiated sites dating back to the Soviet Union require active environmental management that was disrupted nearly a decade ago by Russia’s first invasion in 2014. Now, the areas seeing the highest rates of kinetic activity and destruction are also those with the highest concentrations of risky sites.

The widespread destruction caused by the Russian invasion will inevitably lead to the contamination of land, water, and inhabited environments, where they can persist with a lifespan likely much longer than this conflict. While those risks may pale in comparison to the immediate horrors of war, their risk to human health is real, enduring, and will require focused international attention long after acute violence ceases.

Before presenting a real-time snapshot of the unfolding environmental risks in Ukraine, it is important to understand the nuances associated with these warfare-accelerated risks, specifically the concepts of environmental risk exposure and environmental escalation accelerants.

Environmental risk exposure: dose and time. Environmental risk from toxic substances depends on how long an individual or community is exposed to a given hazard, and at what intensity, or dosage. Pre-existing vulnerabilities of individuals or communities with preexisting exposure risks also factor in. Take, for example, the homes in Irpin, Ukraine that went up in flames after being shelled by Russian troops, most likely emitting both asbestos and particulate matter. For a young, healthy person, even a high dosage rate wouldn’t constitute an immediate risk, although as they age, they might be at an increased risk of cancer respiratory issues. But a young child with asthma or an adult with chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder may face more immediate and acute environmental-related health risks. In one tragic example of this latter scenario, an infant named Amir developed pneumonia after spending extensive periods of time in bomb shelters in heavily-shelled Kharkiv, Ukrainian journalist Kyrylo Loukerenko reported. Amir passed away from this environment-induced respiratory illness after his family fled to western Ukraine to escape the kinetic violence.

As noted by Ukrainian environmental contacts, the pollution exposures in the fight so far operate below the risk calculus of the generally healthy population. Given the Russian Federation’s extensive shelling of residential areas and its civilian targeting, these Ukrainian citizens are focused on their immediate survival; whether they are more likely to develop cancer later in life matters little if they don’t live to old age. This context matters, as does the context of intersecting risk factors. For instance, when a nuclear power plant is shelled, several risks emerge. The potential for radioactive materials to be dispersed from kinetic warfare damage has generated global media coverage. Much less attention has been paid to how nuclear power plants operate as a site of control: whichever conflict party controls the site controls the electricity that it generates. Political control over narratives also intersects with site control. Ukrainian officials have alleged that Russian troops forced Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant employees to record propagandistic addresses about the nuclear program that will be used to justify Russian military activities. And, once seized, the potential risks of such sites provide protection for Russian Forces, as Ukrainians and others are reticent to risk sparking a disaster. These contextual dynamics factor into each individual environmental risks scenario currently unfolding across the geographically large theatre of warfare in Ukraine.

Environmental escalation accelerants: landscape and fighting force variation. In Ukraine, there are two particularly relevant environmental escalation accelerants: the landscape of individual battles and fighting force variation. As we have presented in our research, highly modified urban environments require more active environmental maintenance and management and thus can present risks that rapidly deteriorate when serving as a site of warfighting. Russia is escalating the conflict, increasing the number of missile, air, and artillery strikes, especially in urban centers, so environmental conditions will likely worsen. Warfare in cities like Kyiv, Kharkiv, Mariupol, Zaporizhzhia, and others also increase the likelihood of damaging critical infrastructure that will in turn unleash diverse environmental ramifications, like ruptured dams flooding industrial waste sites. We have also observed the Russian Federation’s invasion resulting in a heavy military presence in ecologically fragile areas, such as the Chernobyl exclusion zone, heightening soil, water, and air risks. While fighting or military convoy passages in rural areas may not have the same degree of concentrated environmental risk, these areas will see unique environmental ramifications as well. And Ukraine’s sprawling agricultural lands require a different type of environmental management to ensure productive harvests and fertile soil. In order to resume farming operations after the war, these areas, now potentially contaminated with military debris and particulate, will require various levels of environmental remediation.

Many people have already observed important distinctions within the Russian Federation fighting force composition, which displays varying levels of military professionalism, ranging from poorly trained Russian conscripts to Russian riot control units to more professionalized Russian special forces and other fighters including from Chechnya. These varying levels of training, competence, and professionalization may also play into environmental disaster escalation. While direct orders are likely behind outright environmentally hazardous behavior, such like the shooting of the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, other environmental risks have been introduced as the result of corruption or incompetence. In one example, military analysts noted the failure of Russian vehicle tires to be properly rotated in the months prior to the invasion, causing them to become stuck in muddy conditions, leaching chemicals into the soil as the tires decompose while the vehicle’s tailpipes pump out emissions trying to escape the quagmire. Understanding both the direct, willful introduction of environmental contaminants into this environment due to warfare and direct orders, along with those introduced by a lack of professionalization, are both important to understanding the full environmental risk portrait across Ukraine. Even imprecise targeting of weapons systems by military personnel can lead to increased rates of environmental hazards, from either striking the wrong target or requiring greater amounts of firepower to achieve the desired effect. That said, broad destruction of infrastructure appears to be the current goal.

Sites of urgent environmental risks. The Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant in southeastern Ukraine is located just seventy-five miles from the city of Zaporizhzhia, home to roughly three-quarters of a million citizens. Well-known in Ukrainian history for its historic connection to the Zaporizhzhian Cossacks, the island of Khortytsia in the city of Zaporizhzhia is famous for the unique flora and fauna associated with its forests, meadows, and steppe. The city is an important industrial center for Ukraine, where aircraft engines, cars, substation transformers, steel, aluminum, and other heavy industrial goods are produced. The province is also home to the Zaporizhzhia thermal power station, the Dnipro Hydroelectric Station, and the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, the largest nuclear power station in Europe.

The power plant itself poses several potentially catastrophic environmental risks, especially if damaged by military operations. Recent fighting at the facility has brought this to international attention, and for good reasons. There are 150 spent nuclear fuel rod storage facilities on site with a mix of cooling pools and dry cask storage, both of which require active management and protection, in addition to the six reactors and myriad other potentially hazardous materials on site. There are also other environmental risks the site intersects with by nature of what it does. The Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant provides a quarter of all of the grid electricity in Ukraine. It is needed to heat homes, refrigerate food and medicines, and power water treatment and provisioning systems, to name a few critical functions. As such, the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant presents primary and secondary risks to the immediate area and the broader region.

One hundred kilometers due north of the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant is the Pridniprovsky Chemical Plant. This chemical plant is in the central-eastern town of Kamianske (Dnipropetrovsk Oblast), home to a quarter-million people. The Pridniprovsky Chemical Plant was once the biggest uranium processing site in the Soviet Union. Located within a Soviet closed city—in which entire settlements were constructed, kept off maps, and maintained as closely guarded secret cities—the plant produced bomb-grade materials for the Soviet nuclear arsenal. Today, the plant houses approximately 40 million tons of radioactive waste, which a 2020 Bellona report noted was more than 15 times the amount of nuclear waste housed within the infamous Chernobyl nuclear reactor Number 4. This quantity of nuclear waste so close to a river-port residential town has long posed serious environmental concerns, including the possibility that pollution could spill into the Dnipro River waterway and down to the Black Sea, but sat neglected during the tumultuous decade-and-a-half following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Today the site is just north of the line of Russian Federation forces in southern Ukraine. Much has been written about the possibility of a missile or artillery strike damaging the site and dispersing toxic substances. Less attention has been paid to the risk of flooding if upstream dam infrastructure was targeted or accidentally damaged. An influx of water could mobilize and further distribute the toxic tailings stored on site—essentially toxic residue sludge ponds—along the Dnipro River. Clearly, it is not just fighting at the site itself that could create substantial environmental hazards but also damage to upstream infrastructure that this site, and many others, are connected to by virtue of human modification and complexification of the ecosystem.

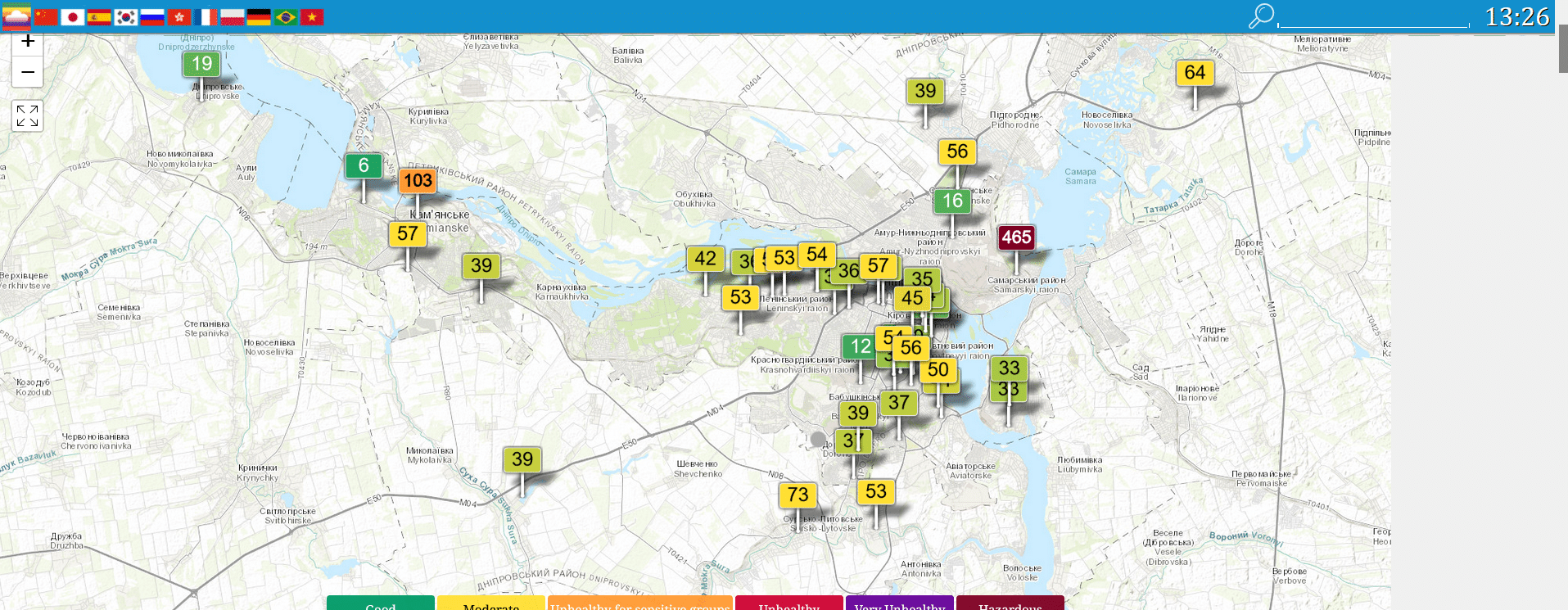

Wartime emissions. Whether from burning buildings, vehicle exhaust, or smoldering fuel depots, the increase in hazardous air pollution exposures has substantially increased across Ukraine. According to a source at the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources, Ukraine’s air quality monitoring infrastructure went offline early in the invasion due to a server being destroyed in a missile strike, although other resources exist to monitor declining air quality. Publicly-available data allows international observers to watch the battles and destruction unfold in real-time via air quality monitoring sensors stationed throughout the major cities. However, these public monitoring tools have also had large numbers of sensors go offline either due to direct damage or damage to the power source or servers. Many of the industrial cities of Ukraine had air quality hazard issues prior to the outbreak of war. Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources officials say they have now substantially increased despite the major drop in emissions from more common sources of pollution—like industrial production, transportation, and energy facilities—that dropped off as people fled and normal daily activities ceased. The emissions of warfare have more than filled the gap.

At the time of writing, international and Ukrainian officials and scientists continue to monitor the environmental risks and other potential flashpoints, although monitoring gaps are a growing problem. (The International Atomic Energy Agency announced that it lost contact with safeguards monitoring systems at Chernobyl on March 8.) Where they are available, damaged site assessments (industrial factories, oil and gas pipelines, areas with legacies of nuclear testing ranging from Chernobyl to the Donbas), logs of damaged infrastructure, air quality monitoring data, and hospital logs of patients with toxic exposure injuries are critical to understanding this context now, and later.

The only way to arrest the growing humanitarian crisis and the unfolding environmental crisis, which “constitute[s] a great threat to the whole continent,” is to end the violence and re-establish Ukrainian governmental control of environmentally fragile sites.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.