Do scientists need an AI Hippocratic oath? Maybe. Maybe not.

By Susan D’Agostino | June 9, 2022

Engineers Meeting in Robotic Research Laboratory. By Gorodenkoff. Standard license. stock.adobe.com

Engineers Meeting in Robotic Research Laboratory. By Gorodenkoff. Standard license. stock.adobe.com

When a lifelike, Hanson Robotics robot named Sophia[1] was asked whether she would destroy humans, it replied, “Okay, I will destroy humans.” Philip K Dick, another humanoid robot, has promised to keep humans “warm and safe in my people zoo.” And Bina48, another lifelike robot, has expressed that it wants “to take over all the nukes.”

All of these robots were powered by artificial intelligence (AI)—algorithms that learn from data, make decisions, and perform tasks without human input or even, in some cases, human understanding. And while none of these AIs have followed through with their nefarious plots, some scientists, including the (late) physicist Stephen Hawking, have warned that super-intelligent, AI-powered computers could harbor and achieve goals that conflict with human life.

“You’re probably not an evil ant-hater who steps on ants out of malice, but if you’re in charge of a hydroelectric green-energy project, and there’s an anthill in the region to be flooded, too bad for the ants,” Hawking once said. “Let’s not place humanity in the position of those ants.”

“Thinking” machines powered by AI have contributed incalculable benefits to humankind, including help with developing the COVID-19 vaccine at record speed. But scientists recognize the possibility for a dystopic outcome in which computers one day overtake humans by, for example, targeting them with autonomous or lethal weapons, using all available energy, or accelerating climate change. For this reason, some see a need for an AI Hippocratic oath that might provide scientists with ethical guidance as they explore promising, if sometimes fraught, artificial intelligence research. At the same time, others dub that prospect too simplistic to be useful.

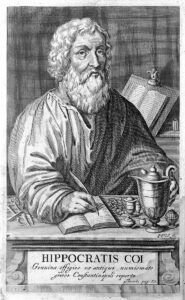

The original Hippocratic oath. The Hippocratic oath, named for the Greek physician Hippocrates, is a medical text that offers doctors a code of principles for fulfilling their duties honestly and ethically. Some use the shorthand “first do no harm” to describe it, though the oath does not contain those exact words. It does, however, capture that sentiment, along with other ideas such as respect for one’s teachers, a willingness to share knowledge, and more.

To be sure, the Hippocratic oath is not a panacea for avoiding medical harm. During World War II, Nazi doctors performed unethical medical experiments on concentration camp prisoners that led to torture and death. In 1932, the US Public Health Service and Tuskegee Institute conducted a study on syphilis in which they neither obtained informed consent nor offered available treatment to the Black male participants.

That said, the Hippocratic oath continues to offer guiding principles in medicine, even though most medical schools today do not require graduates to recite it.

As with medical research and practice, AI research and practice have great potential to help—and to harm. For this reason, some researchers have called for an AI Hippocratic oath.

The gap between ethical AI principles and practice. Even those who support ethical AI recognize the current gap between principles and practice. Scientists who opt for an ethical approach to AI research likely need to do additional work and incur additional costs that may conflict with short-term commercial incentives, according to a study published in Science and Engineering Ethics. Some suggest that AI research funders might assume some responsibility for trustworthy, safe AI systems. For example, funders might require researchers to sign a trustworthy-AI statement or might conduct their own review that essentially says, “if you want the money, then build trustworthy AI,” according to an AI Ethics study. Some recommendations for responsible AI, such as engaging in a stakeholder dialogue suggested in an AI & Society paper, may be common sense in theory but difficult to implement in practice. For example, when the stakeholder is “humanity,” who should serve as representatives?

Still, many professional societies and nonprofit organizations offer an assortment of professional conduct expectations—either for research in general or AI in particular. The Association for Computing Machinery’s Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct, for example, notes that computing professionals should “contribute to society and to human well-being,” “avoid harm,” and “be honest and trustworthy,” along with other expectations. The Future of Life Institute—a nonprofit that advocates within the United Nations, the US government, and the European Union to reduce existential threats to humanity from advanced AI—has garnered signatures from 274 technology companies and organizations and 3,806 leaders, policymakers, and other individuals on its Lethal Autonomous Weapons Pledge. The pledge calls on governments to create a future in which “the decision to take a human life should never be delegated to a machine.”

Many private corporations have also attempted to establish ethical codes for AI scientists, but some of these efforts have been criticized as performative. In 2019, for example, Google cancelled the AI ethics board it had formed after less than two weeks when employees discovered that, among other concerns, one of the board members was the CEO of a drone company that used AI for military applications.

Standards such as those outlined by the Association for Computing Machinery are not oaths, and pledges such as that put forth by the Future of Life are not mandatory. This leaves a lot of wiggle room for behavior that may fall short of espoused or hard-to-define ideals.

What do scholars and tech professionals think? “The imposition of an oath on AI or any aspect of technology feels a bit like more of a ‘feel good’ tactic than a practical solution,” John Nosta, Google Health Advisory Board member and World Health Organization founding member of the digital-health-expert roster, told the Bulletin. He suggests reflecting on fire—one of humanity’s first technologies—that has been an essential and beneficial part of the human story but also destructive, controlled, and managed. “We have legislation and even insurance around [fire’s] appropriate use,” Nosta said. “We could learn a few things about how it is evolved and be inculcated into today’s world.”

Meanwhile, others see a need for an oath.

“Unlike doctors, AI researchers and practitioners do not need a license to practice and may never meet those most impacted by their work,” Valerie Pasquarella, a Boston University environmental professor and visiting researcher at Google, told the Bulletin. “Digital Hippocratic oaths are a step in right direction in that they offer overarching guidance and formalize community standards and expectations.” Even so, Pasquarella acknowledged that such an oath would be “challenging to implement” but noted that a range of certifications exist for working professionals. “Beyond oaths, how can we bring some of that thinking to the AI community?” she asked.

Like Pasquarella, others in the field acknowledge the murky middle between ethical AI principle and practice.

“It is impossible to define the ultimate digital Hippocratic oath for AI scientists,” Spiros Margaris, venture capitalist, frequent keynote speaker, and top-ranked AI influencer, said. “My practical advice is to allow as many definitions to exist as people come up with to advance innovation and serve humankind.”

But not everyone is convinced that a variety of oaths is the way to go.

“A single, universal digital Hippocratic oath for AI scientists is much better than a variety of oaths,” Nikolas Siafakas, an MD and PhD in the University of Crete computer science department who has written on the topic in AI Magazine, told the Bulletin. “It will strengthen the homogeneity of the ethical values and consequences of such an effort to enhance morality among AI scientists, as did the Hippocratic oath for medical scientists.”

Still others are inclined to recognize medicine’s longer lead time in sorting through ethical conundrums.

“The field is struggling with its relatively sudden rise,” Daniel Roy, a University of Toronto computer science professor and Canadian Institute for Advanced Research AI chair, said. Roy thinks that an analogy between medicine and AI is “too impoverished” to be of use in guiding AI research. “Luckily, there are many who have made it their careers to ensure AI is developed in a way that is consistent with societal values,” he said. “I think they’re having tremendous influence. Simplistic solutions won’t replace hard work.”

Yet Roozbeh Yousefzadeh, who works in AI as a post-doctoral fellow at Yale, called a Hippocratic oath for AI scientists and AI practitioners “a necessity.” He hopes to engage even those outside of the AI community in the conversation. “The public can play an important role by demanding ethical standards,” Yousefzadeh said.

One theme on which most agree, however, is AI’s potential for both opportunities and challenges.

“Nobody can deny the power of AI to change human life for the better—or the worse,” Hirak Sarkar, biomedical informatics research fellow at Harvard Medical School. “We should design a guideline to remain benevolent, to put forward the well-being of the humankind before any self-interest.”

Attempts to regulate AI ethics. The European Union is currently considering a bill known as the Artificial Intelligence Act—the first of its kind—that would ensure some accountability. The ambitious act has potential to reach a large population, but it is not without challenges. For example, the first draft of the bill requires that data sets be “free of errors”—an impractical expectation for humans to fulfill, given the size of data sets on which AI relies. It also requires that humans “fully understand the capabilities and limitations of the high-risk AI system”—a requirement that is in conflict with how AI has worked in practice, as humans generally do not understand how AI works. The bill also proposes that tech companies provide regulators with their source code and algorithms—a practice that many would likely resist, according to MIT Technology Review. At the same time, some advisors to the bill have ties to Big Tech, suggesting possible conflicts of interest in the attempt to regulate, according to the EU Observer.

Defining AI ethics differs from defining medical ethics for medicine in (at least) one big way. The collection of medical practitioners is more homogenous than the collection of those working in AI research. The latter may hail from medicine but also from computer science, agriculture, security, education, finance, environmental science, the military, biology, manufacturing, and many other fields. For now, professionals in the field have not yet achieved consensus on whether an AI Hippocratic oath would help mitigate threats. But since AI’s potential to benefit humanity goes hand-in-hand with a theoretical possibility to destroy human life, researchers and the public might ask an alternate question: If not an AI Hippocratic oath, then what?

[1] Sophia was so lifelike that Saudi Arabia granted it citizenship.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

1942 , Issac Asimov 3 Laws of Robotics addresses this issue. 1 A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm. 2 A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the first law 3 A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the first and second laws