Review: India’s “Rocket Boys” series fetishizes science—and the atomic bomb—in a dangerous way

By Urvashi Sarkar | June 14, 2022

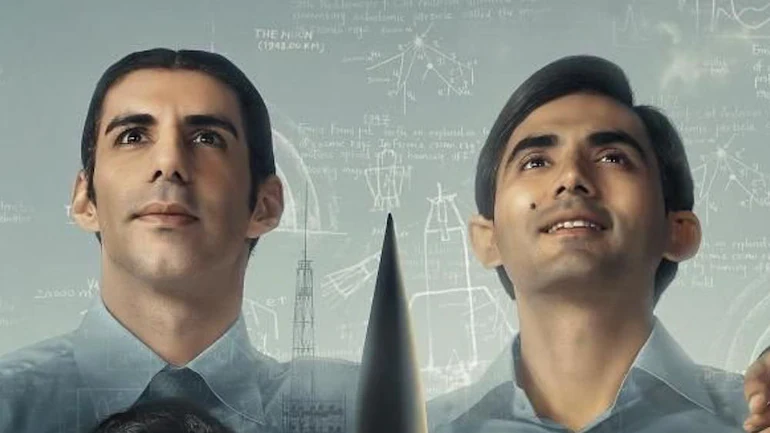

The Rocket Boys web series was released on February 4, 2022 (Image SonyLiv)

The Rocket Boys web series was released on February 4, 2022 (Image SonyLiv)

The year is 1962. China had attacked India. In a friction-ridden meeting of India’s Atomic Energy Commission, the chairman, and scientist Homi J. Bhabha convinces the group to build India’s first atomic bomb. “We can stop any other country from ever thinking of attacking us again,” Bhabha tells the group forcefully.

Not everyone agrees. Bhabha’s long-time friend and fellow Atomic Energy Commission member, Vikram Sarabhai, walks out of the meeting and resigns in protest. “How can you in good conscience do this?” he asks Bhabha.

These are the opening scenes to Rocket Boys, a web series released on February 4, that tells the story of three scientific leaders at the origin of India’s nuclear and space programs—Homi J. Bhabha, Vikram Sarabhai, and A.P.J. Abdul Kalam. Rocket Boys shows similarities with Parmanu, a movie that was released in 2018. Where Parmanu explores the run-up to India’s nuclear tests of 1999 and its aftermath, Rocket Boys depicts the circumstances in which India decided to adopt the path of nuclear energy. While Rocket Boys makes for engaging drama, does it tell this story with due diligence to scientific and historical facts? Unfortunately, the answer is resoundingly in the negative.

The web series received early positive reviews in the media. But scholars well-versed in the history of these programs soon exposed glaring flaws in the science and the problematic ways in which key personalities are presented. The narrative conveniently plays into the dominant hyper-nationalist narratives prevailing in India and deepens fault lines in Indian society.

Twisting reality. In a piece appropriately headlined “As a historian of the nuclear program, I can only laugh at the howlers in Rocket Boys,” political scientist Itty Abraham mentions a scene in which a fully-suited Bhabha jumps into a radioactive swimming pool reactor to repair malfunctioning fuel rods. He is supposed to get the reactor up and running in time for Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s visit. The scene is intended as suspenseful and nail-biting. But it is simply not credible; no nuclear physicist would do such a thing.

Abraham—author of The Making of the Indian Atomic Bomb: Science, Secrecy and the Postcolonial State—also criticizes the sequences showing the runup to India’s first rocket launch, scenes that portray India’s scientists as careless and inept. “Bhabha and Sarabhai would be horrified to think that their pioneering vision and extraordinary achievements were being reduced, decades later, to the celebration of last-minute screwdrivers and ropes pulling up launch platforms,” he writes.

Journalist Gita Aravamudan, who has been closely associated with the Indian space program and personally knew several individuals portrayed in Rocket Boys, writes about being “appalled at the liberties that have been blithely taken. … [T]he science has been subsumed completely by the need to make the two main rocket boys cool.” The irony, Aravamudan adds, is that the actual story of India’s space program is so dramatic and intriguing that the fictional embellishments adopted by Rocket Boys were unnecessary.

Insidious script. Aravamudan wryly writes that watching Rocket Boys feels like a bad Bollywood movie in which iconic scientists have been turned into the worst of scientist stereotypes.

To add further drama to the web series, Bhabha is pitted against an adversary, Mehdi Raza, a fictional character evidently inspired by the Indian astrophysicist Meghnad Saha. Yet the portrayal of Raza is immensely problematic, stealing from Saha’s formidable reputation and personality, only to twist it in egregious ways. Saha was one of India’s most towering scientists of the time, in the same league as Bhabha. He built India’s first cyclotron—which Raza in the series is shown as doing—and also established the Institute of Nuclear Physics in Kolkata.

Of particular note, Rocket Boys distorts Saha’s background in an insidious way. Saha was Dalit—the most repressed and discriminated social group in India, earlier known as untouchable and treated as outcaste. Yet the makers of the web series borrow from Saha’s professional background using it to flesh out an adversary who is Muslim, deliberately cashing in on dominant anti-Islamist currents in India. In a further manipulation of truth, the series shows Raza as cozying up with the CIA to subvert India’s nuclear program—when Saha was a socialist who was inspired by Soviet planning and tried to replicate it in India.

Rocket Boys does attempt to give a glimpse into the personal lives of Bhabha and Sarabhai, exploring their relationships with their families and the women in their lives. But since two men are the chief protagonists of the series, the women appear as largely romantic props instead of fully fleshed-out characters and fade out only to suddenly reappear in a few scenes.

Good acting. There is a redeeming feature in Rocket Boys—the superlative acting by Jim Sarbh and Ishwak Singh, who play Bhabha and Sarabhai respectively.

The arguments between Sarabhai and Bhabha as best friends and sparring partners are some of the most watchable moments of Rocket Boys. The two scientists come to life as they debate an independent India’s future, scientific progress, their ambitions, and their love lives. Homi Bhabha is portrayed as a debonair maverick and prodigy and Sarabhai as his foil—quiet, razor-sharp, and unafraid to challenge his mentor, Bhabha.

Above all though, Rocket Boys eulogizes science’s role in elevating a poor and newly independent nation in the 1960s. “Science by the late colonial period was burdened with an unrealistic set of expectations. It came to be regarded as how India would reverse centuries of underdevelopment,” writes Sankaran Krishna in the 2009 edited volume, South Asian Cultures of the Bomb: Atomic Publics and the State in India and Pakistan. Indian elites offered to achieve nuclear power status as a response to the abysmal state of general economic development in the country, he adds.

The release of Rocket Boys earlier this year comes at a time when India’s growth, prosperity, and progress are seriously questioned. Its nostalgic tone and fetishizing of science—and the atomic bomb—match the beats of the ultra-nationalist and jingoistic media and political narratives dominating India’s present-day public discourse. Unfortunately, that discourse and the Rocket Boys series both play loose with facts and bend reality in potentially dangerous directions.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: India, nuclear energy, nuclear risk, nuclear weapons, review

Topics: Analysis, Nuclear Energy, Nuclear Weapons