New roots of famine:

How climate crises and global conflict combine to threaten millions in the Horn of Africa

By Erik English

Design by Erik English and Thomas Gaulkin

August 18, 2022

Radio Ergo, a news outlet that focuses on humanitarian news in the Horn of Africa, recently reported on the plight of Hawo Adan Shuriye, a widow with nine children in central Somalia’s Galgadud region. She was forced from her home by conflict between the Somali national army and the paramilitary forces of Ahlu Sunnah Wal Jama’a.

According to the radio station, Hawo lost dozens of goats during a skirmish last year. She had previously collected two containers of milk daily from her goats, worth about three dollars. “You can see we are sheltering under trees that we have wrapped up with clothes. We have no proper shelter here, no food. We have no one else except Allah,” she told Radio Ergo. “What I am now left with are four goats. I looked for the lost goats for about a month, but I have now lost hope of getting them back,” she told Radio Ergo.

Flimsy shelters for displaced families. (Radio Ergo)

Hawo is one of many thousands. The ongoing drought in the Horn of Africa—which scientists say has been intensified by climate change—has led to an extraordinary humanitarian crisis as large areas of Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia teeter on the brink of famine. But the drought is only partly to blame for the suffering. Two other significant threats are contributing to the likelihood of famine: food shortages caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and regional and insurgent conflict preventing aid from reaching those most in need. Meanwhile, large numbers of people have been forced—by failed crops and war—to migrate, creating hygiene and water problems that have led to serious disease outbreaks.

It is a visceral, visible illustration of what many climate scientists have predicted: A 21st century world in which less developed, poorer, and drier regions of the world are made ever more miserable as climate change progresses and intersects with other major threats to humanity.

A bad drought, even by Horn of Africa standards.

The drought, which began in 2020, has now lasted through its fourth rainy season. There are usually two rainy seasons each year in this part of Africa, the wettest between March and May and a shorter rainy season between October and December.

According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), the four rainy seasons between October 2020 and today “were all marred by below-average rainfall, leaving large swathes of Somalia, southern and south-eastern Ethiopia, and northern and eastern Kenya facing the most prolonged drought in recent history. The March–May 2022 rainy season is likely the driest on record.” Forecasts for the October-December 2022 rainy season are not promising either.

Today, more than 18 million people across Kenya, Ethiopia, and Somalia are classified as food insecure—meaning they lack regular access to enough safe and nutritious food for normal growth and development—due to the drought, and the number of people with high levels of acute food insecurity could reach 20 million by September.

Food and water are becoming scarcer, prices are rising, and disease is spreading. Aid efforts are being further hampered by conflict and a deepening global food crisis.

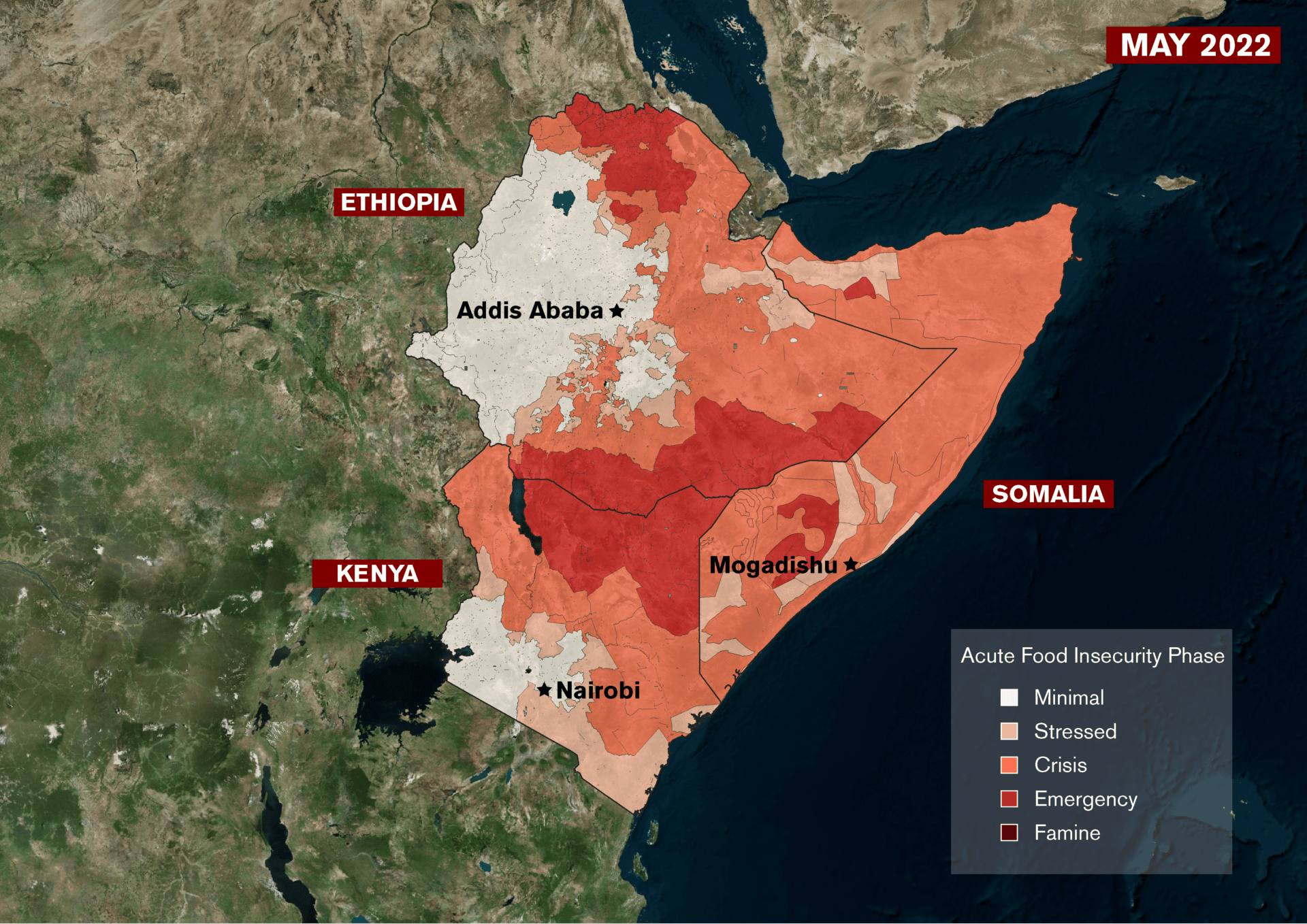

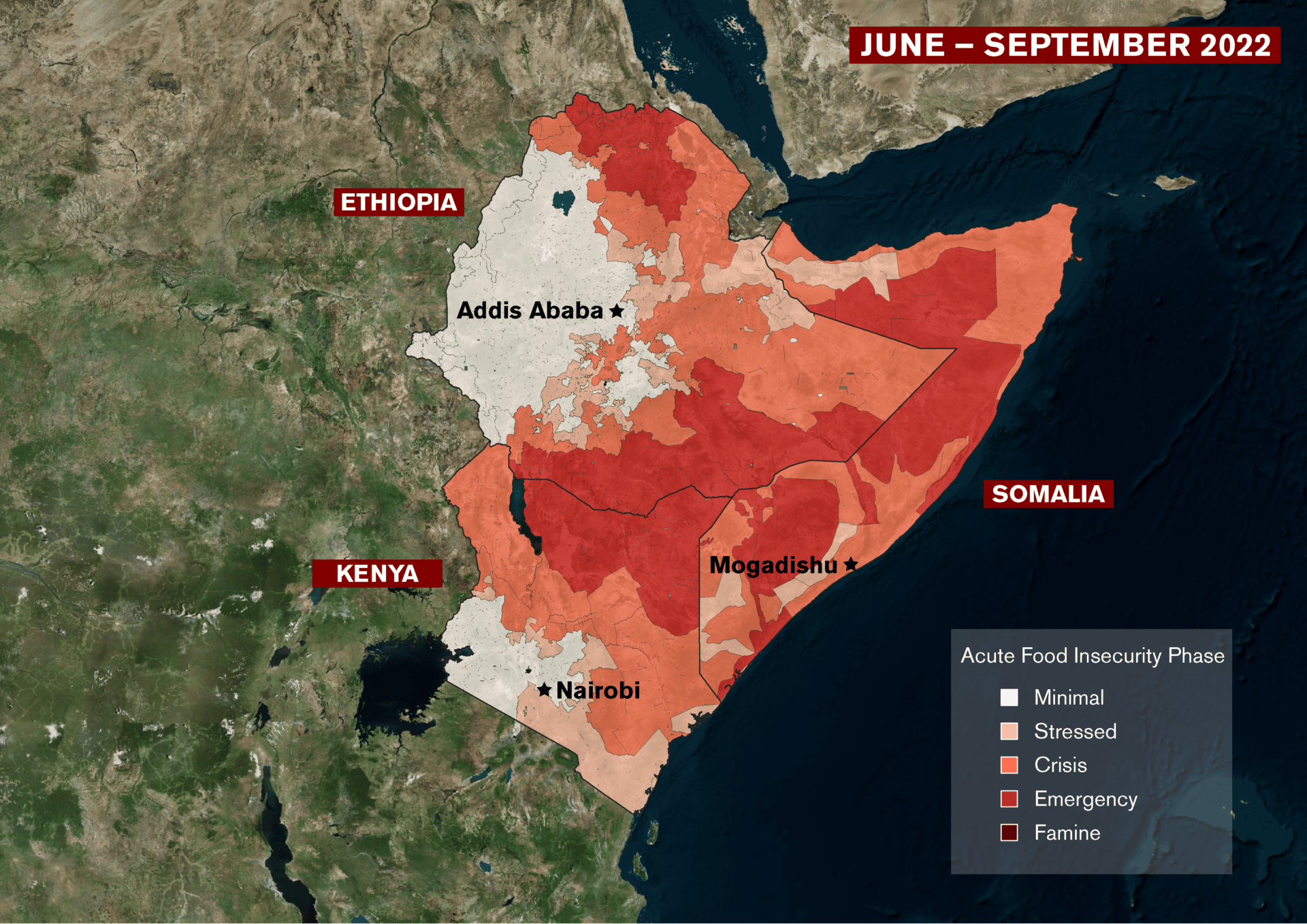

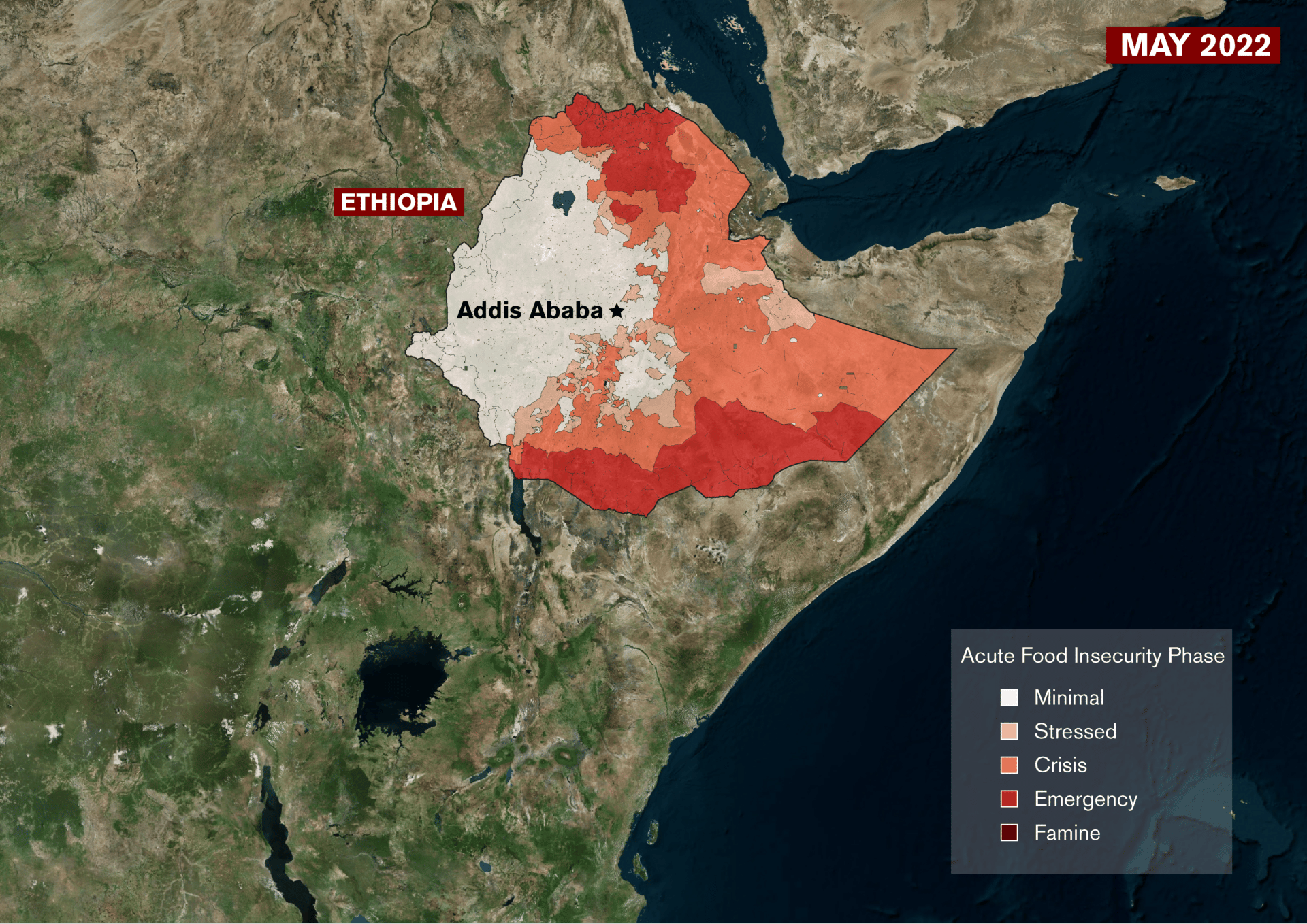

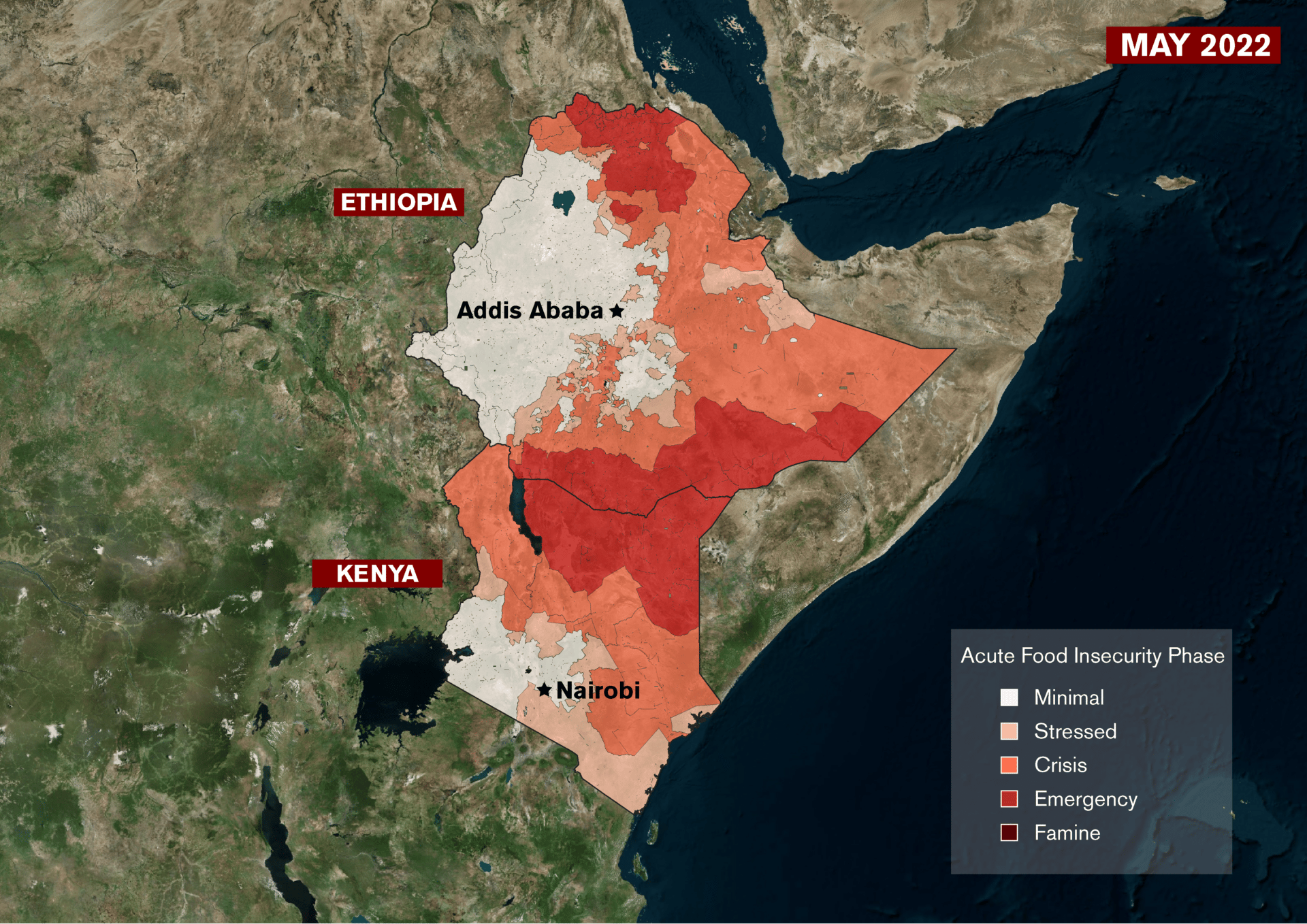

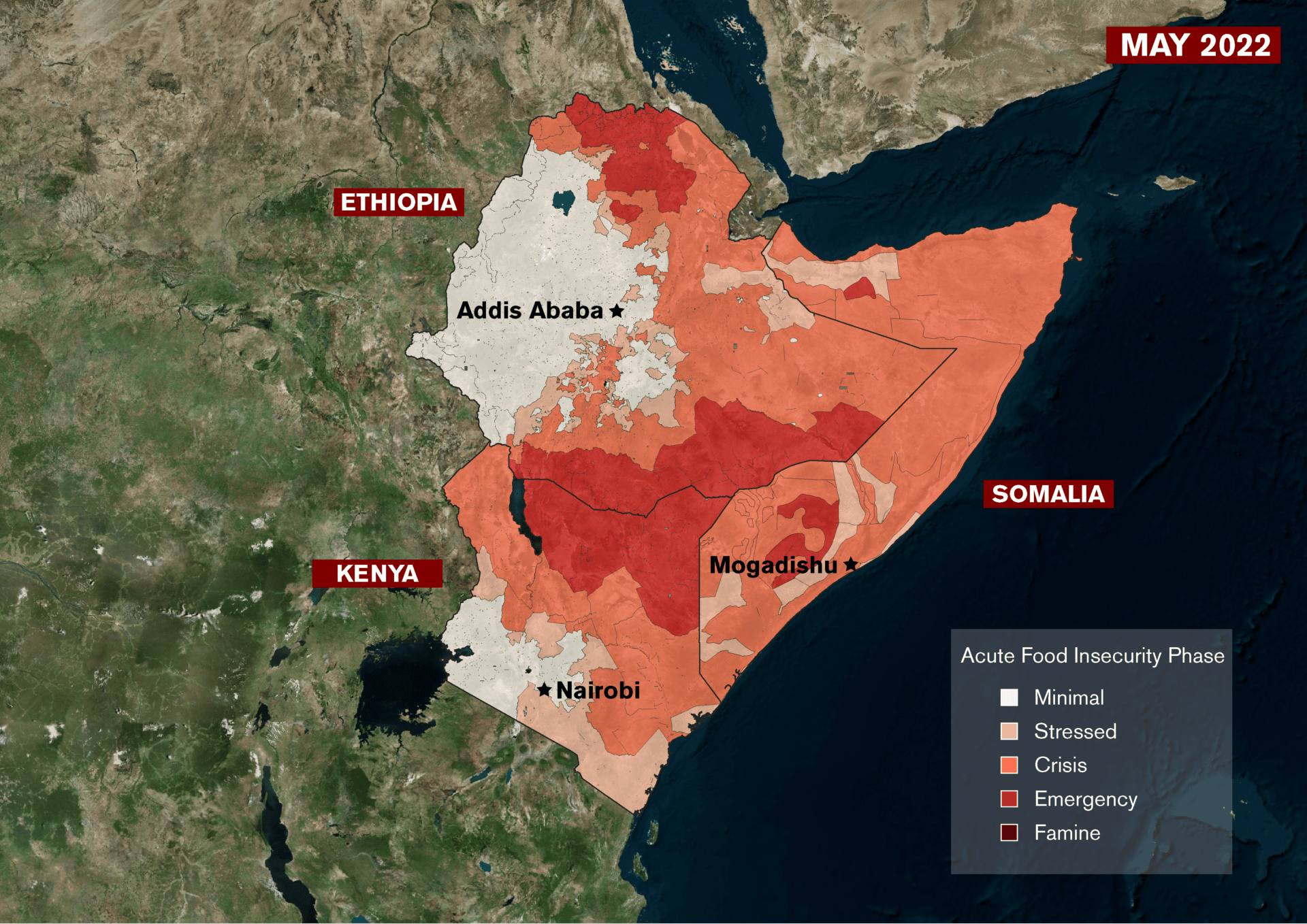

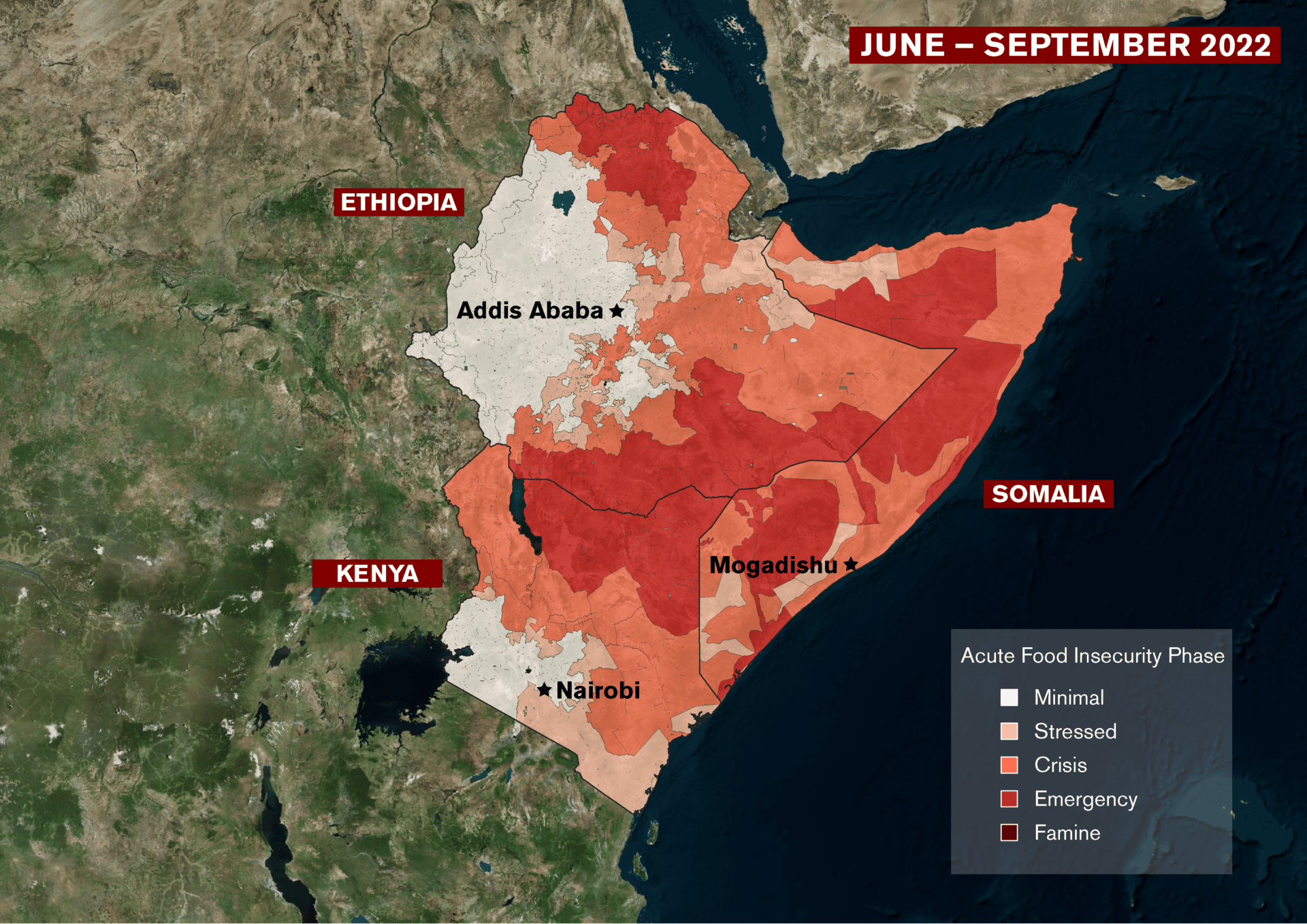

Forecasts by the Famine Early Warning System Network (FEWS NET) show how much more grave the situation can become.

These two maps show how rapidly acute food insecurity is spreading across the Horn of Africa, as measured by the Famine Early Warning Systems Network. More than 18 million people across Kenya, Ethiopia, and Somalia are now classified as food insecure, and the conditions in May (above) are forecast to continue deteriorating through September (below). In Ethiopia, the drought is affecting the southern and eastern regions, while in Kenya it has spread in the northern pastoral regions. Virtually all of Somalia is affected by the drought. (Maps by Erik English)

More than 18 million people across Kenya, Ethiopia, and Somalia are classified as food insecure.

In Ethiopia, the drought is affecting the southern and eastern regions.

In Kenya, the northern pastoral regions are most affected.

Virtually all of Somalia is affected by the drought.

The situation will worsen as the drought drags on.

These maps show how rapidly food insecurity is spreading across the Horn of Africa, as measured by the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET). More than 18 million people across Kenya, Ethiopia, and Somalia are now classified as food insecure, and the situation observed in May (above) is forecast to continue deteriorating through September (below). (Maps by Erik English)

So far, more than 7 million livestock have died across the Horn of Africa due to the drought. In addition to lost livelihoods and resources, this means that children have less access to milk, thereby worsening malnutrition. At the end of July, more than 7.1 million children were acutely malnourished, including two million who are “severely” acutely malnourished, according to OCHA and UNICEF.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), “Increasing levels of under nutrition and micronutrient deficiencies will increase health risks and needs especially of pregnant and lactating mothers, of new-born, of children, of the elderly and of people living with chronic diseases (including TB and HIV) and disabilities.”

As livestock die and crops shrivel, many have been forced to flee their homes in search of food and water.

Migration complicates the crisis.

Migrations and mass displacements can worsen the situation as poor hygiene and sanitation become the new norm on the road, where there is less access to safe drinking water and health services. Even before the drought, immunization rates were low, and years of underinvestment and conflict had made health care services in short supply across this part of Africa.

Consequently, cholera, measles, and diarrhea are all on the rise in the region. The WHO says it is providing vaccinations for as many at-risk groups as possible.

“Ensuring people have enough to eat is central. Ensuring that they have safe water is central. But in situations like these, access to basic health services is also central,” said Michael Ryan, executive director of WHO’s Health Emergencies Programme. “Services like therapeutic feeding programmes, primary health care, immunization, safe deliveries and mother and child services can be the difference between life and death for those caught up in these awful circumstances.”

Families are resorting to desperate measures to feed themselves. Child marriage has increased, as families marry off young girls to reduce financial burdens and earn money to buy food. Others are engaging in increasingly risky behavior like underpaid labor and prostitution, according to the WHO.

Persistent drought is increasing food insecurity and displacement. More than 7 million children were facing acute malnutrition at the end of July. (Humanitarian Information Unit)

The causes of famine

Around one million livestock are believed to have died in drought-affected parts of Somali Region, Ethiopia. (UN Ethiopia / Getachew Dibaba)

The causes of famine

The risk of famine in the region is very real, but it is a fallacy to blame drought or any other single natural disaster for creating famine. When asked about the role that drought and other natural disasters play in creating famine, Alex de Waal, director of the Word Peace Foundation, called it “nonsense.” “Famine is a very specific political product of the way in which societies are run, wars are fought, governments are managed. The single overwhelming element in causation—in three-quarters of the famines and three-quarters of the famine deaths—is political agency,” he said.

In terms of the current situation in the Horn of Africa, two significant threats are contributing to the likelihood of famine beyond drought: food shortages caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and regional and insurgent conflict that is preventing aid from reaching those most in need.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Washington Post reports that in Somalia, “A kilo (2.2 pounds) of potatoes in Dolow cost 50 cents in March; now it’s $1. Cooking oil has gone from $5 a liter (about a quarter of a gallon) to $13 a liter. Therapeutic food packets have shot up from $40 a carton to $47 in recent months.”

Historically, even though drought has become associated with the Ethiopian famine from 1983 to 1985, experts have pointed out that “widespread drought occurred only some months after the famine was already under way.” Instead, the majority of the blame for that famine—which became the subject of major international media attention—should have fallen on the government and the civil war raging at the time. The methods of that war prevented communities from accessing food and water. “It is not war itself that creates famine, but war fought in particular ways” de Waal said in a study of the famine.

Today in Ethiopia, conflict in the north of the country is considered a separate crisis from the drought in the south and the east, but forecasts of food insecurity expect the northern areas to remain the highest concern for famine in the short term due to insecurity. The northern outlook is expected to improve beginning in October, but the southern and eastern outlooks continue to worsen.

In 1991, Somalia’s dictator, Siad Barre, fled the country and the population was plunged into a civil war that led to famine. The years since have devastated the farming industry and most food staples are now imported. As a result, Somalia is much more vulnerable to trade disruptions like those resulting from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. To make matters worse, the terrorist group al-Shabob is making it harder for the aid that exists to reach those most in need.

Radio Ergo explains the situation this way: Water is the main issue facing villages in Somalia; they are serviced by tankers and the roads are not always safe for travelers because of conflict. Or as The Economist put it, in somewhat starker terms, “[In Somalia,] aid workers rarely venture out to the countryside for fear of having their heads cut off by al-Shabab.”

Whatever aid is able to reach the most in need is often fodder for corruption, making Somalia the most at risk for famine in the region.

Political violence in the Horn of Africa since 2020

Political violence in the Horn of Africa since 2020

Map of political violence within Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia with at least 1 fatality since 2020. (The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project)

Map of political violence within Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia with at least 1 fatality since 2020. Source: The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (Map by Erik English)

“To save lives, aid agencies will have to tolerate more risk,” Daniel Maxwell of Tufts University in Boston says. “These risks are not just to their workers but also their reputations. Some worry about facing criminal charges in America under counter-terrorism laws if aid falls into the hands of jihadists.”

Not the first, nor the last.

The United States has announced $1.3 billion in aid to the Horn of Africa region, focused on providing water, food, and medicine. Furthermore, ships loaded with grain have started navigating the mined waters off of Ukraine for the first time since the war began. That is good news for families like Hawo’s, but the threat throughout the region remains grave. This is a tragedy for those who have already lost their lives, an emergency for those whose lives can be saved, and a harbinger of what’s to come.

Even as the nations of the world fight to reduce their emissions and the threat of climate change, much damage has already been done. Even if all emissions ended today, global average temperatures will continue to climb, extreme droughts, flooding, and climate refugees will be increasingly common.

Climate refugees and natural disasters made worse by climate change can potentially inflame political tensions, creating the conditions for famine and mass starvation. That doesn’t mean they’re inevitable. Governments choose how to spend money and where their priorities lay. All of this is a choice.

As the Russian invasion of Ukraine shows, nuclear threats are real, present, and dangerous

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent, nonprofit media organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Africa, biosecurity, climate change, drought, famine, food insecurity

Topics: Biosecurity, Climate Change

Share: [addthis tool="addthis_inline_share_toolbox"]

US drone strikes in Somalia aren’t helping matters.