Winter is coming: Europe’s huge geopolitical blunder on Russian energy

By Michal Wyrebkowski, Wiktor Babinski | October 14, 2022

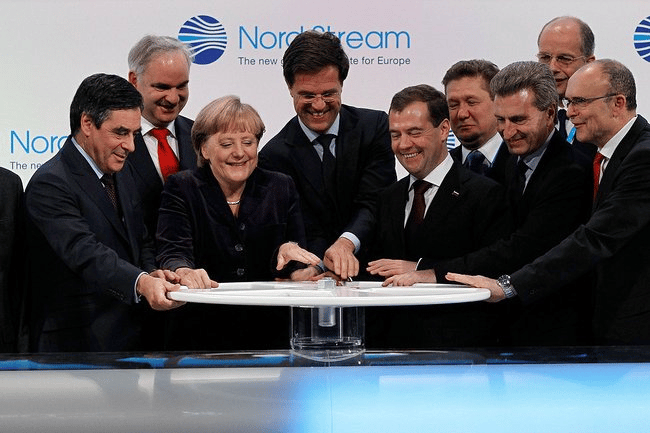

German Chancellor Angela Merkel, French Prime Minister François Fillon, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev, and other world leaders at the November 8, 2011, launch ceremony for the first leg of the Nord Stream gas pipeline. Credit: Office of the President of Russia

German Chancellor Angela Merkel, French Prime Minister François Fillon, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev, and other world leaders at the November 8, 2011, launch ceremony for the first leg of the Nord Stream gas pipeline. Credit: Office of the President of Russia

As winter approaches, European governments are preparing to weather a storm that threatens not only the comfort and safety of their citizens, but also the recently regained Western unity on foreign policy. The looming “energy crisis” is widely discussed at high-minded conferences, in parliamentary speeches, and in the media—where politicians use it to make and deflect accusations, and tabloid headlines warn that doomsday is descending on Europe.

How did it come to pass that some of the world’s richest countries are fearing for their ability to heat homes in the winter? And why did a significant part of the most secure military alliance in contemporary history allow itself to become dependent on a potential geopolitical rival that had long shown alarming intentions?

Europe’s current predicament is a story of flawed strategic thinking—based on false assumptions about geoeconomics in general, and Russia in particular—that goes back to the closing years of the Cold War. It is the greatest geopolitical blunder of the European Union in the 21st century.

From energy cooperation to weaponization. Europe’s contradictory relationship with Russia in the sphere of energy resources began in the 1970s, during the détente that temporarily thawed the Cold War. Italy, France, and West Germany moved to increase imports of Soviet hydrocarbons, and invested the capital and technology necessary to develop Siberian oil fields. With the emergence of a pipeline network linking the Soviet Union to Western Europe, and the energy crisis induced by the OPEC cartel, Russia emerged as a key supplier of Western European energy.

That this arrangement survived the frost age in East-West relations during the Reagan era foretold a wider political pattern: Western Europe began perceiving Russian energy imports as a useful economic reality that could be conveniently exempted from geopolitical considerations, often in spite of evidence to the contrary. Despite the clear economic benefits of this relationship for the Soviet Union and its successor, the Russian Federation—both of which used energy windfalls to bankroll a struggling great-power project—Moscow never stopped thinking of its energy relationship with Europe in geopolitical terms.

Modern Russian foreign-policy doctrine is inextricably linked to the weaponization of energy exports. Although the Soviet Union withdrew its military and political presence from Central Europe, it did not completely give up its influence there. Soviet diplomats Valentin Falin and Yuli Kvitsinsky proposed an alternative arrangement to replace military influence with economic leverage and make Europe dependent on energy exports. During the three decades since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Russian government employed in Europe a carrots-and-sticks policy on energy resources. Europe’s single greatest geopolitical mistake was to deepen its energy cooperation with Russia while at the same time blatantly ignoring Russia’s weaponization of this purportedly solely economic relationship, which was mostly visible in Central and Eastern Europe.

Pipeline politics. Most of the pipelines built under the Soviet Union were westbound. This is hardly surprising, given that they were built by German and Austrian companies in pipelines-for-gas deals of the late 1960s.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, when the new Russian Federation was desperately strapped for cash in the 1990s, the independent countries that rose from the ashes of the communist empire and inherited former Soviet gas pipelines gained important leverage with Russia. The dependency was mutual. Belarus and Ukraine depended on cheap gas and transport fees, while Russia did not have any other route to Western Europe for the transportation of natural gas. But as Russia recovered from its 1990s economic slump, the threat of energy weaponization became more and more credible.

Russian energy interventions surged as Moscow started building up its reserve fund after the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis and Russian bankruptcy. In order to establish what Gleb Pavlovsky and Sergey Chernishov, Kremlin’s leading “political technologists” in the early 2000s, dubbed the “Transnational Corporation Russia,” Vladimir Putin embarked on a quest to geopolitically leverage Russia’s role as an energy supplier.

In the early 2000s, the Latvian port of Ventspils, which was connected to Transneft’s Russian pipelines through a northern branch of the 5,500-kilometer (3,418-mile) Druzhba pipeline, was the main export route for Russian oil. In 1999, the Russian multinational corporation Lukoil exported 32 percent of all Russian oil exports via the Latvian port. In 2002, Ventspils exported bigger volumes of Russian oil and petroleum than any other ports in the former Soviet Union—14.9 million metric tons and 7 million metric tons, respectively. In 2003 a delegation of the Russian Council of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs presented a de facto ultimatum—there would be no more Russian oil exports through Ventspils unless the Latvian government sold its share in the port to a Russian company and granted voting rights to the Russian inhabitants of Latvia who were not its citizens. Despite rising oil prices and high profit margins on exports, the Russians cut off oil supplies to Ventspils. It was one of many cases of Moscow’s resolve to forgo short-term profits for the sake of expanding its economic and political sphere of influence.

To further its goal of controlling oil assets in the Baltic, Russia cut off its oil exports to the Mazeikiai oil refinery in Lithuania—the only major oil production facility in the entire region. It was one of the last of the Yukos Oil Company assets that was up for sale during the convoluted nationalization process of Russia’s biggest private oil company. The Kremlin used Lukoil as an economic proxy to attempt to buy the Lithuanian refinery, but it ultimately went to the highest bidder—the Polish national energy company PKN Orlen. Moscow responded by cutting off the Mazeikiai oil refinery from the Druzhba pipeline, which increased the cost of operating the refinery but did not stop the Polish company from buying the refinery. A mysterious fire at the oil refinery further increased its operational costs in the first two years following the purchase. In spite of these challenges, the Polish government decided to realize its doctrine of long-term energy security even at a short-term economic cost, in order to prevent Russian economic expansion into the Baltic region.

Russia also made multiple attempts to undermine Ukraine by using energy as leverage. Before the Orange Revolution, the price of gas sold in Ukraine was heavily subsidized by Russia. In 2005, Ukrainian residential customers on average paid only $36.60 per thousand cubic meters of gas (TCM), compared with an average price for the European Union of $160 to $230 per TCM. As Ukraine’s government changed to an explicitly pro-Western one, Russia cut gas supplies to Ukraine for three days starting on January 1, 2006, and after negotiations was able to raise the price to about $100 per TCM.

Disputes about price levels, debt repayments, and intermediaries continued—together with Russian threats—until they culminated in the 2009 gas crisis, in which Russia cut off gas supplies to Ukraine on January 1 and then significantly reduced supplies to the European Union four days later. The crisis was only partly due to economic reasons: bills unpaid by Ukraine’s Naftogaz, Ukraine’s largest national oil and gas company. It was primarily meant to shake the foundations of then-Ukrainian Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko’s pro-Western government and the presidency of Viktor Yushchenko, who defeated Putin’s favorite candidate in a contested election.

Hooked on Russian gas. All these attempts to enclose the so-called “near abroad” within the Russian sphere of influence were highlighted and documented, but Western European states, in particular Germany, continued using Russian gas. In Germany, gas was envisioned as a bridge fuel between fossil fuels and renewable energy during the energy transition known as the Energiewende. Due in part to the historic strength of the Green anti-nuclear movement, Germany decided to phase out nuclear power after the 2011 Fukushima disaster, and lacked sufficient battery storage for renewable energy. Natural gas accounted for 15.3 percent of German electricity generation in 2021, and 32 percent of that gas hailed from Russia.

Germany’s drive toward gas as a transitional fuel—and Western Europe’s entire post-Cold War energy strategy—has proved to be an abject failure. It put Germany on a longer and riskier road to climate neutrality. The German energy plan was based on the assumption that an authoritarian state, if woven into a network of energy relationships, would be a peaceful and reliable partner. Putin’s Russia proved this wrong by destroying the European security architecture.

The lesson for Western countries is that they must pay more attention to where their energy resources come from. Energy sourcing will become increasingly important in the coming years, coinciding with de-globalization.

In retrospect, pushing for an early nuclear phase-out was also a grave mistake. Germany abandoned a low-emissions source of energy and made itself more reliant on Russian gas. Extending the life of three nuclear reactors that remain operational has already been ruled out, which shows how politically difficult it is to advocate for nuclear energy in Germany, even in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Two of the reactors will be put in cold shutdown, to be used only in case of an energy emergency.

Reducing Russian influence. European Union institutions and some Eastern European countries have adopted a much more sensible approach to energy policy. While international consortiums were building the Nord Stream 2 pipeline to deliver natural gas from Russia to Germany, Poland built the Baltic Pipe to Norway and interconnectors with Lithuania and Slovakia, which have decreased their reliance on the Soviet legacy supply chains and created a new supply corridor for the European gas market.

European Union legislation has also played a key role in preventing the expansion of the Russian energy influence. The union’s Third Energy Package, implemented following the 2009 Ukraine gas crisis, effectively prevented the Russian state-owned energy corporation Gazprom from launching the Nord Stream 2 pipeline: The package included an “unbundling” rule that prohibited Gazprom from being both the pipeline operator and its gas supplier. The European Commission also played a pivotal role in brokering a deal to reduce gas demand by 15 percent this winter, and is considering gas price caps akin to the price caps on Russian oil that have successfully driven down the prices of oil futures.

The European Union’s response to the energy crisis is still being undermined by energy policy makers. One example is the French reluctance to approve the Iberian Express pipeline, which energy analysts view as a necessary element for weaning Europe off Russian gas. Liquid natural gas terminals on the Iberian peninsula are underutilized and stranded from the rest of the European gas grid.

Similarly, battles over the EU Taxonomy—a classification system designed to help investors make sustainable choices—did little to reassure gas developers and sponsors that liquid natural gas projects have a long-term future and are needed to displace coal globally. The same applies to the developers of nuclear power plants, which can replace some of the gas demand for electricity production in the long term.

Mitigating the effects of the energy crisis will require a common European solution—and what is at stake is not only survival during the coming winter, but the integrity of the European energy market and the European Union at large. The massive investment supported by European nations must be coupled with lifting price controls, further unbundling, market-based trading of pipeline capacity, and many other liberalization measures at the European Union level to support the development of Europe’s gas market. The process of weaning Europe from Russian energy influence will require radical changes in energy markets and gas geoeconomics, as proposed by experts at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy. It will not be easy to fix the decades-long European blunder.

The sources of Europe’s current energy crisis lie in a convenient and complacent economic relationship laden with geopolitical risks. That Western Europe refused to see—despite painfully obvious evidence—the risks of becoming economically entwined with a potential adversary that prioritized geopolitical leverage over economic considerations, was Europe’s greatest blunder of the 21st century.

Western Europe chose to patronize its Eastern neighbors who joined the European Union after 2003, and dismissed their reasonable geopolitical concerns as “Russophobia” and political immaturity. In the face of a debilitating energy crisis caused by the war in Ukraine, Europe has a unique chance to reflect on its mistakes.

There are hopeful signs that this is already happening. The German foreign minister admitted in August that Germany had been paying for the supposedly “cheap” Russian gas with its “security and independence”. With this reflection sinking in, Europe needs to craft a prudent and coherent strategy for the future that recognizes the unbreakable relationship between economics, energy security, and geopolitics.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: energy crisis, natural gas, oil exports, pipeline

Topics: Nuclear Energy, Opinion, Voices of Tomorrow

The answer to the question is much simpler than described here and has more to do with geology than politics.

Russia accounts for 13% of the earth’s land surface (without Antarctica and Greenland) and therefore (statistically) also of the raw materials. If you consider only Eurasia, which is more accessible for Europe, it is even 31%. It makes no economic sense to forego this, especially if one takes into account that East Asia needs a lot for its own consumption.

Now Yale has spoken to Europe: more nuclear! More gas! — but gas from the US (fracking) instead of from Russia. Never mind the climate. More long term commitment to pipelines through France which does not want it! Never mind democracy; the Germans have rejected nuclear power in several elections from 1998 on. They have replaced nuclear and much of the coal with wind and solar. Of course they could have done more, but they have done a lot. The world boom for wind and solar started in Germany. Wyrebkowski and Babinski think that the EU taxonomy is not gas-friendly… Read more »