War puts cleanup of Russia’s radioactive wrecks on ice

By Charles Digges | November 28, 2022

The Soviet submarine K-159 sank on August 30, 2003 while being towed to be dismantled, killing 9 people. (The Bellona Foundation)

The Soviet submarine K-159 sank on August 30, 2003 while being towed to be dismantled, killing 9 people. (The Bellona Foundation)

Read this article translated into Russian here.

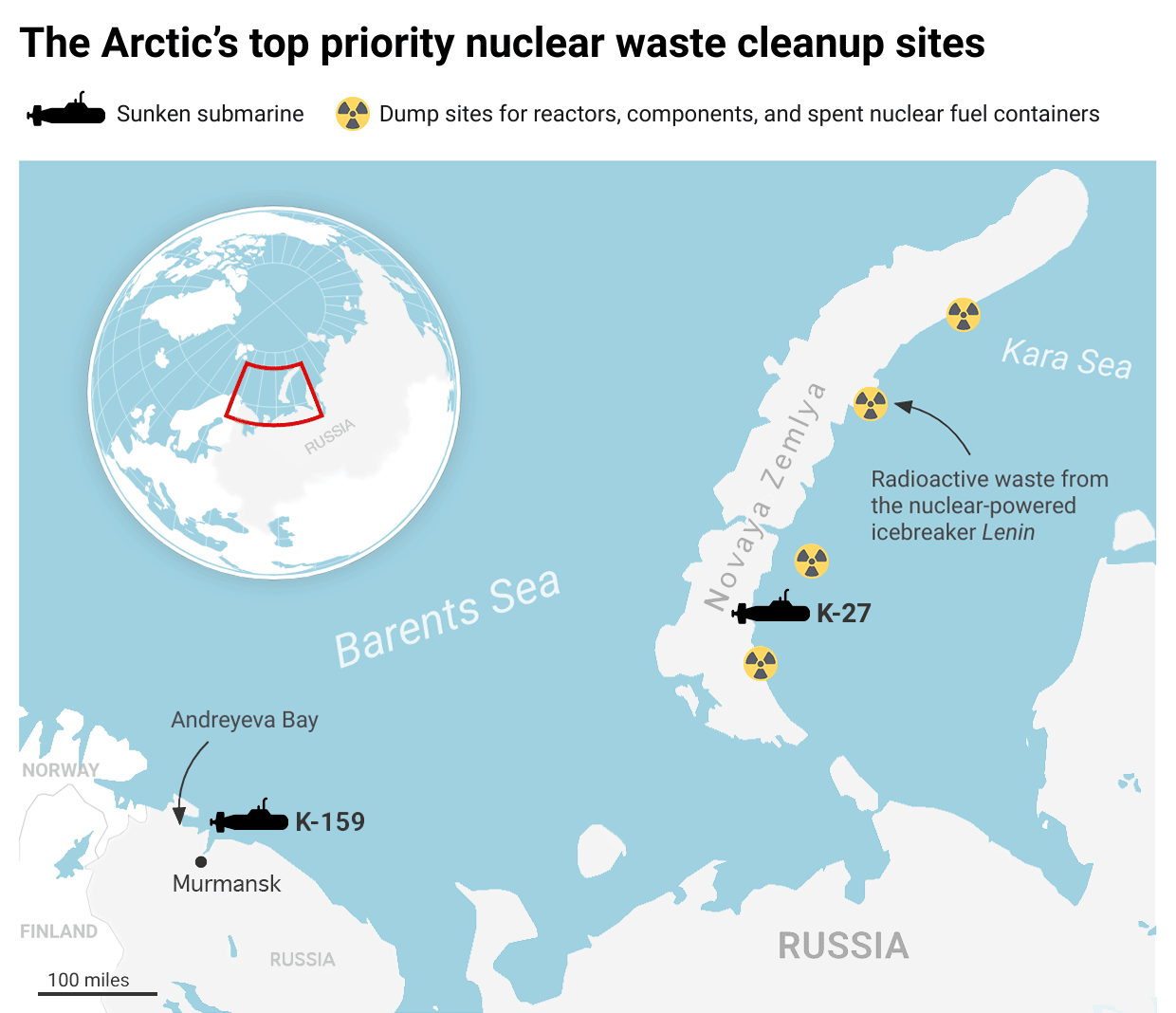

When Russia assumed the rotating chairmanship of the Arctic Council in 2021, Moscow brought the environmentally minded eight-nation body an ambitious proposal. Over the next 14 years, it would raise from the depths of the Arctic a toxic array of rusting nuclear garbage—including two entire nuclear submarines—that had been dumped during the Soviet era.

The project was estimated to cost about $394 million at current exchange rates and had the backing of Vladimir Putin. His Arctic development plan ordered the retrieval of the subs and the accompanying radioactive waste by 2035.

Russian gas, oil, and mineral conglomerates wanted the wrecks cleared away from nascent Arctic shipping routes. Fishermen from either side of Russia’s border with Scandinavia, concerned that radioactive leakage from the submarines’ reactors would contaminate fisheries, also celebrated the news. It was a rare alignment of the stars, pleasing environmentalists, business interests, the Kremlin, and European governments all at the same time.

By November 2021, discussions were underway with the powerful European Bank of Reconstruction and Development, which promised to help fund a preliminary review to establish how the subs should be lifted.

Then, in February, Russia invaded Ukraine.

Since then, the West has imposed a raft of sanctions against Moscow, and the intergovernmental buzz on the Arctic submarine and radioactive junk lift has gone silent.

Norway was among the first to step back, ceasing scientific exchanges with Moscow as soon as May and pausing funding to its decades-old bilateral nuclear safety commission with Russia in June. Days later, Moscow retorted tartly, saying it, too, was ceasing its work with the commission over the “unfriendly line” Norway had taken since the beginning of hostilities in Ukraine.

For an alliance that had weathered political tremors as turbulent as Moscow’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, the rift was profound. Even when mutual distrust between East and West had been high, Norway and Russia had been able to reach above the politics to safely dispose of the most toxic elements of Cold War history. But the invasion of Ukraine proved to be a last straw.

Moscow insists that it will lift the submarines on its own. But does it stand any chance of doing so by itself? And if it can’t, what is at stake?

A history of cooperative cleanup. Throughout the Cold War, the Soviet Union and the United States built more than 400 nuclear submarines, assuring each superpower the ability to fire nuclear missiles even after their land-based silos had been decimated by a first strike. The fjords and coastlines around Murmansk adjacent to NATO member Norway became the hub of the Soviet Northern Fleet, and a dumping ground for radioactive waste and spent nuclear fuel.

After the Iron Curtain fell, the disturbing scale of this legacy came to light. It was revealed that at Andreyeva Bay, a nuclear submarine refueling site just 60 kilometers from the Norwegian border, 600,000 metric tons of irradiated water leaked into the Barents Sea from a nuclear fuel storage pool in 1982. The site contained 22,000 spent nuclear fuel assemblies pulled from more than 100 subs, many kept in rusted containers stored in the open air.

Fearing contamination, Norway spearheaded a sweeping cleanup effort with other Western nations. Combined they spent more than $1 billion to dismantle 197 decommissioned Soviet nuclear subs that rusted dockside, still loaded with spent nuclear fuel. One thousand Arctic navigation beacons powered by strontium batteries were replaced, many with solar powered units provided by the Norwegians.

What is still in the sea? Like numerous other countries, including the United States, the Soviet Union had a habit of dumping its radioactive problems at sea.

The 1993 White Book—a sort of confession to this dumping published by crusading ecologist Alexei Yablokov when serving as Boris Yeltsin’s environmental minister—outlined the scope of the problem, though for years its revelations continued to be viewed by many in the Russian government as state secrets.

A 2019 feasibility study for the sub lifting project, drawn up by the Norwegian Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority with the help of other European nuclear safety agencies, confirmed Yablokov’s data and laid bare what the Soviets had intentionally sunk: 18,000 radioactive objects, including 19 vessels and 14 nuclear reactors.

While the radiation emitted by most of these cast offs has been smothered to near background levels thanks to decades of built-up undersea silt, a study by the Russian Academy of Sciences nonetheless identified 1,000 objects that still produce high levels of gamma radiation.

Ninety percent of that radiation is emitted by six objects that Rosatom, Russia’s state nuclear firm, has deemed urgent and targeted for lifting: two nuclear submarines; the reactor compartments from three nuclear submarines; and the reactor from the legendary icebreaker Lenin.

“We consider even the extremely low probability of radioactive materials leaking from these objects as posing an unacceptable risk for the ecosystems of the Arctic,” Anatoly Grigoriev, Rosatom’s head of international technical assistance, said in July.

The two nuclear submarines—which together contain one million curies of radiation, or about a quarter of that released in the first month of the Fukushima disaster—pose the greatest challenge to lift and have received most of the press.

The first of these is the K-27. Launched in 1962, the 360-foot sub suffered a radiation leak in one of its experimental liquid-metal cooled reactors after just three days at sea. Over the next several years, the Soviet navy attempted to repair or replace the reactors, but in 1979, they gave up and decommissioned the vessel.

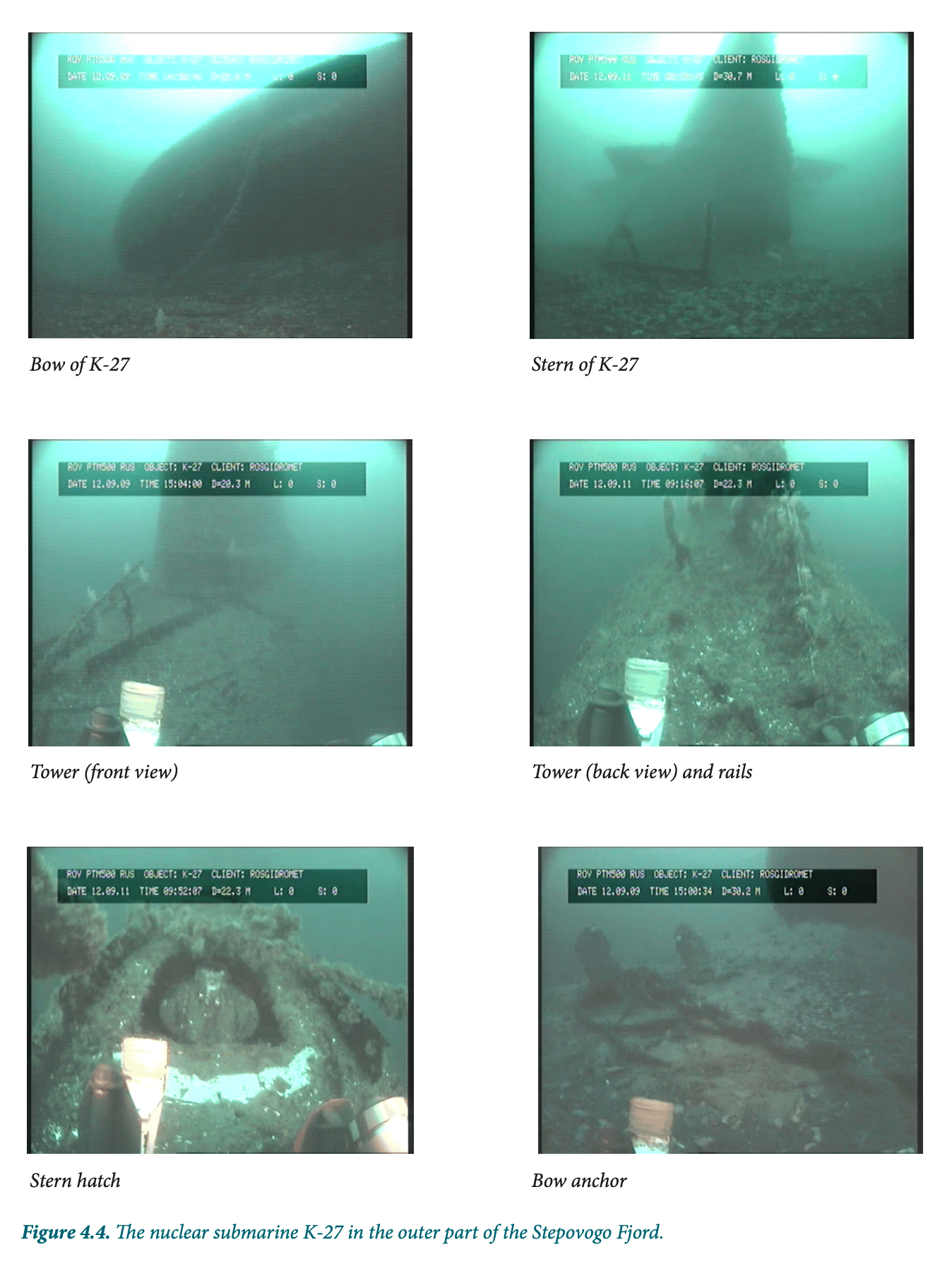

Too radioactive to be dismantled conventionally, the K-27 was towed to the Arctic Novaya Zemlya nuclear testing range in 1982 and scuttled in one of the archipelago’s fjords at a depth of just 33 meters. The sinking took some effort. The sub was weighed down by asphalt to seal its fuel-filled reactor and a hole was punched in its aft ballast tank to swamp it.

But the fix won’t last forever. The sealant around the reactor was only meant to stave off radiation leaks until 2032. More troubling still is that the K-27’s highly enriched fuel could, in the right circumstances, generate an uncontrolled nuclear chain reaction leading to a significant local release of radiation.

The other submarine, the K-159, was in use from 1963 to 1989. It was added to the toxic subsea catalog in 2003, after the Cold War’s end. But its position north of Murmansk, astride some of the Barents Sea’s most fertile fishing grounds and busiest shipping lanes, has made it a source of special anxiety. Already a 305-foot rust bucket from years of neglect, the K-159 sank while being towed to a Murmansk shipyard for dismantlement, killing nine sailors who were on board to bail out water in transit.

Unlike the K-27, however, no safeguards to secure the K-159’s two reactors were put in place before it sank, meaning it went down loaded with 800 kilograms of spent uranium fuel.

The danger the subs pose to the environment. Expeditions to the subs in recent years haven’t revealed serious upticks in contamination beyond background radiation levels. A joint Norwegian-Russian mission to the K-159 in 2018 discovered breakage along the sub’s hull, but, as in years previous, reported no elevated radiation levels in sediment and seawater samples.

Similarly, a Russian expedition to measure radioactivity around the K-27 this past October, which charted contamination levels in glaciers surrounding Novaya Zemlya, found nothing amiss.

But experts from both sides of the Russian border say that such circumstances won’t last. Officials at the Norwegian Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority insist that leaks from the K-159 are only a matter of time—and that even rumors of increased contamination could damage the Arctic fishing industry.

Alexander Nikitin—a former Russian Navy submarine captain with Norway’s Bellona Foundation who sat on Rosatom’s public advisory council before it disbanded over the Ukraine war—agreed. In his accounting, the subs will continue to degrade and slowly release cesium 137 and strontium as water seeps into the reactors.

A 2013 study by Norway’s Institute of Marine Research used computer simulations to model what impact that might have on local populations of cod and capelin, Norway’s Arctic cash crop. The study showed that if all the radioactive material from the K-159’s reactors were to be released in a single “pulse discharge,” it would increase the levels of slow-decaying cesium 137 in the muscles of cod in the eastern Barents Sea at least 100 times.

That would still be below limits set by the Norwegian government following the Chernobyl disaster in 1986. “Here the question is that some of the radionuclides leached out of the reactors can get into fish—and the fish onto someone’s dinner table,” Nikitin said. “It’s difficult to estimate the impact.”

Even low doses, he said, would be enough to scare consumers off Norwegian fish. As of 2021—a decade after the Fukushima accident — there were still 15 countries banning the import of seafood from Japan, despite numerous studies establishing acceptably low concentrations of radionuclides in fish caught in that area.

By one estimate, a ban on fish from the Kara and Barents Seas could cost the Norwegian and Russian economy a combined $140 million a month—an economic hardship that some say would be worse that any direct environmental damage.

Will Russia do it alone? Moscow has stumbled in its first solo steps on this project. As recounted with unusual candor by Atomnya Energia, a Russian nuclear industry trade publication supported largely by Rosatom itself, the project can’t even secure financing from Russia’s Ministry of Finance, which called Rosatom’s cost projections “insufficiently substantiated.”

“But how can I substantiate the cost of work that has never been done before?” the publication quoted Rosatom’s Grigoriev as lamenting. Russia also blew past a deadline to deliver an overarching road map outlining how the project would be undertaken due to bureaucratic confusion and squabbles.

One problem: Russia lacks the kind of special vessels that can lift a submarine. The last time the country attempted such an operation, the Kursk, a 17,000-metric ton vessel, sank during a military exercise in August 2000. That botched rescue attempt fueled indignation at Putin, who was then less than a year into his first presidential term.

After delaying the arrival of Norwegian rescue divers to the Kursk for nine days, during which time the surviving crew perished, the Kremlin was quick to invite the Dutch companies Mammoet and Smit International to coordinate the technically demanding raising of the wreck a little more than a year later.

With the Dutch, and anyone else, almost surely unwilling to help, Russia is alone with trying to build its own salvage vessels to lift the K-27 and K-159—ship construction that would inflate the estimate cost of the lifting operation by another several million dollars.

Numerous designs for such a ship have been batted about—employing anything from balloons to giant pincers to lift the subs—but nothing has come of them. At the July conference, Oleg Vlasov, who heads Malakhit, Russia’s federal marine engineering bureau, complained that he didn’t have enough technical information about the wrecks from Rosatom, despite the numerous expeditions to them, to even begin designing such a vessel.

“We’ve been talking too much and for too long,” Oleg Vlasov, who heads Russia’s federal marine engineering bureau, warned Rosatom in July. If Russia doesn’t act soon, he said, the vessels will become so enfeebled in their watery graves that it might be safest to leave them where they are.

It is this scenario that Nikitin finds the most likely after the invasion of Ukraine.

“The issue of lifting these sunken objects will continue to be postponed and obscured, and the authorities will begin to explain that they don’t pose a serious threat, and that over time they’ll become safer, and so on,” he said.

He added that none of the Rosatom meetings about the sub lift that he attended prior to the invasion of Ukraine had focused on Russia building its own vessels to lift the subs. Rather, they focused on which countries to ask to lift them.

But Nikitin and other members of Russian civil society who made up Rosatom’s public council won’t be attending more such meetings in the foreseeable future. And transparency on the Russian side—honed over many difficult years—might be one of the biggest environmental casualties of Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.