The Biden administration overestimates radiological terrorism risks and underplays biothreats

By Zachary Kallenborn | March 17, 2023

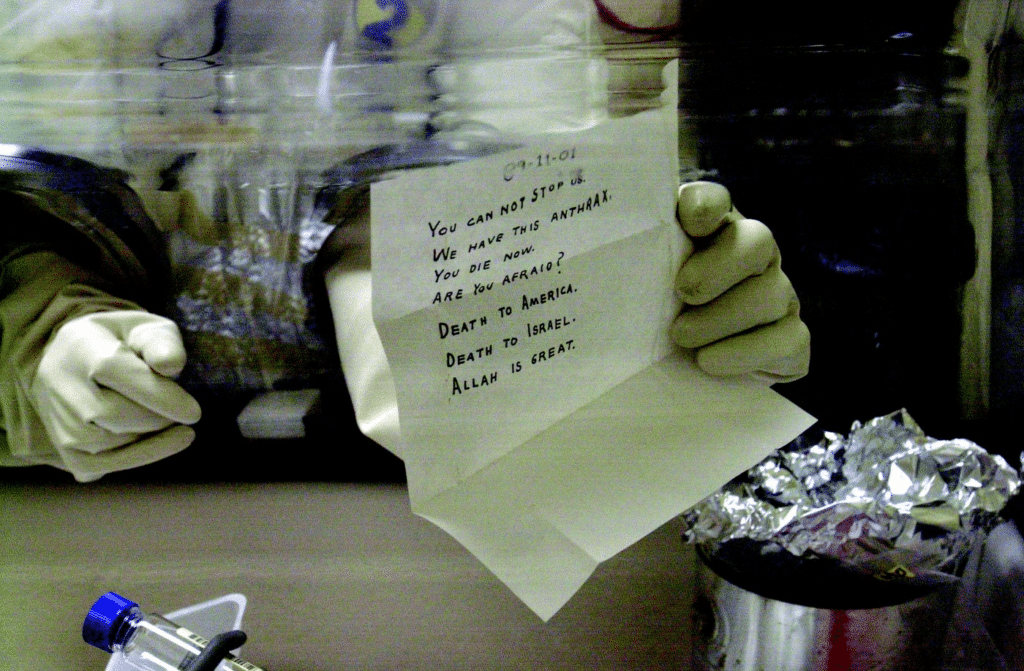

A piece of evidence from the Amerithrax investigation into anthrax-laced postings. Credit: FBI.

A piece of evidence from the Amerithrax investigation into anthrax-laced postings. Credit: FBI.

President Joe Biden earlier this month signed a new national security memorandum to counter weapons of mass destruction (WMD) terrorism. The memorandum is classified, but a publicly accessible fact-sheet sets out the American strategy to combat WMD terrorism, including by preventing terrorists from accessing WMD material, detecting and deterring threats, and enhancing domestic and international capabilities to counter WMD terrorism. In particular, the plan emphasizes the safeguarding of nuclear and radiological material, which could be diverted into weapons. In one crucial respect, however, the administration gets it wrong.

Although the anti-terror strategy’s focus on nuclear security is somewhat justified given the potential for massive harm, the radiological security emphasis is not. Rather, the emphasis should have been on biological terrorism. Among WMD terrorism modes, bioterrorism risks are increasing most, even if the overall likelihood remains low. At the same time, new mass casualty terror threats are emerging that do not neatly fit into the WMD terrorism framework. The administration’s memorandum can be compared to a police department that prioritizes serial killers and jaywalkers. One priority can be defended, but does not capture the full scope of concerns; the other is, frankly, a bit odd.

An insignificant threat? In a radiological attack, a terrorist might use an explosive like dynamite to contaminate a target with radioactive material. So-called “dirty bombs” are different from nuclear weapons like atomic bombs, which, by splitting atoms, release a huge amount of explosive energy. Of all the forms of WMD terror—usually conceived of as attacks that use chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear weapons—radiological terrorism attacks are easily the lowest risk.

There have been basically no successful examples of radiological terrorism, and attempts are rare, even for already-rare WMD terrorism. START’s Global Terrorism Database, which documents over 200,000 terrorist attacks domestically and internationally, includes only 13 incidents of radiological terrorism, none of which caused any injuries or deaths. And one man carried out 10 of the attacks: Tsugio Uchinishi, a Japanese man who mailed monazite powder, which contains the radioactive element thorium, to various Japanese agencies to warn the government about exports of uranium to North Korea. Although reports that the Islamic State acquired 40 kilograms of uranium generated plenty of media attention, uranium is not actually all that radioactive and would have caused minimal harm, especially compared to other Islamic State attacks. The reality is radioactive material does not add much to a terror attack, except a tad bit more economic harm and unwarranted media attention.

Even theoretically, the consequences of radiological terrorism are quite low. In a dirty bomb, most of the harm comes from the explosion. The radioactive material creates an increased risk of cancer while adding to potential clean-up costs. Even in the most extreme forms, the primary harm is as a weapon of mass disruption: closing an important port, say, until a costly clean-up can be completed. Although inciting a nuclear meltdown could conceivably cause mass harm, it’s extraordinarily difficult due to existing protections and the administration’s “radioactive material security” program does not appear to do anything for nuclear power plant security anyway. Compare the radiological terror consequence to a nuclear terrorist attack that could destroy a city, or an extreme bioterrorism attack that could conceivably kill more people than have died in the COVID-19 pandemic. The difference is stark.

In fairness, the accessibility of radiological material drives the risk. Blood transfusion devices in many hospitals use highly radioactive cesium-137, for example. Even household smoke detectors can have very small amounts of radioactive material, though a massive amount would be required to make a dirty bomb of any consequence. The memorandum, therefore, is useful in risk reduction, even if radiological terrorism does not deserve such a high priority in the administration’s anti-terror plans.

Emerging WMD threats. Among WMD terrorist threats, the barriers to bioterrorism are going down the most. Synthetic biology provides a pathway for terrorists to acquire highly controlled pathogens, such as the variola virus (the causative agent of smallpox). 3-D printing enables printing materials for lab equipment and potentially easier access to harmful pathogens, too. Online marketplaces also offer an avenue to acquire laboratory equipment usable in biological weapons programs with limited oversight. Plus, ubiquitous drone technology could be relatively easily used for the dispersal of chemical and biological weapons agents. Of particular concern are agricultural drones for dispersing pesticides, which are practically purpose-built to deliver biological weapons agents. These developments are leading to a broader de-skilling (or at least a shift in the type of skills required) of the expertise needed to develop and use biological weapons agents.

This is not to say bioterrorism is easy. Even if a terrorist used synthetic biology to acquire a pathogen, acquired pesticide drones to deliver the aerosol, and used 3-D printing and online markets to acquire lab supplies and equipment, the terrorist would still need to mass produce the pathogen and weaponize it without a lab accident or discovery by law enforcement. Consequently, successful bioterror attacks are rare, and, despite alarms, COVID-19 is unlikely to change that possibility much.

But unlike radiological terrorism, terrorists have pulled off major biological weapons attacks and attempted extreme forms. The START Global Terrorism Database documents 38 incidents of bioterrorism, most significantly the Rajneeshee cult attack that sickened 751 in the Dalles, Oregon in 1984. And, of course, in the so-called Amerithrax attacks in 2001, mailed letters containing bacillus anthracis (the causative agent of anthrax) killed five and injured 17. There have also been major attempts, such as Aum Shinrikyo’s failed attempts to use biological weapons to ignite an apocalyptic war, and the radical environmentalist group RISE’s attempt to wipe out humanity and re-populate the Earth with environmentally sensitive revolutionaries.

At the same time, new WMD terrorist threats are emerging. Drone swarms are a new WMD, given their ability to cause mass harm and lack of reliability. Although terrorists still face considerable difficulty in acquiring true drone swarms with intra-swarm communication, the risk is trending upward. At the same time, developments in nanotechnology—a branch of technology interested in manipulating matter at the nano-scale (1 to 100 nanometers)—offer terrorists a new means to acquire chemical and biological-terrorism-like weapons. Cyberterrorism is also plausible, with the growth of the internet of things offering new vulnerabilities for hostile actors to cause harm.

What should have been done? Overall, the Biden administration plan does provide a good baseline for addressing the continued threat of WMD terrorism. Despite the focus of US security policy moving away from terrorism to counter the rise of China, WMD terrorism still deserves serious attention, especially as governmental pressure on disrupting terror organizations wanes. But the policy specifics should align more directly with the threat landscape, current and future.

Given the growing risks of bioterrorism risks, US officials should have a particular focus on searching for and sharing information about radicalized experts. Access to relevant technical expertise still remains a major barrier, and building biological weapons requires significant tacit knowledge, the subtle knowledge that comes from working in a lab for a long time that cannot be explained. The best example is Aum Shinrikyo; despite being incredibly well-resourced, its biological weapons program struggled. In one case, a cult member fell into a fermenting tank of clostridium botulinum, the bacteria that produce the botulinum toxin that is lethal in microgram amounts—and emerged unharmed. The cult had over $1 billion in assets, yet was unable to acquire the necessary skills for a successful bioattack.

In addition, the United States should undertake national and global efforts to improve biosecurity and biodefense, especially concerning synthetic biology. For example, the United States might focus on facilitating and encouraging discussion between different scientific disciplines and global regulators concerning genetic engineering regulations, domestically and globally. Similarly, a recent US Government Accountability Office (GAO) review found 21 of 29 long-standing recommendations to improve US biodefense remain unimplemented. The United States could also encourage transparency, education, and risk reduction around the global proliferation of biosecurity level 3 and 4 (BSL-3 and BSL-4) laboratories that handle the world’s deadliest pathogens.

The United States also needs to update the global framework for combating WMD terrorism to address new threats. UN Security Council Resolution 1540 prohibits states from providing support to chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear terrorism and requires the adoption and enforcement of laws to prevent proliferation—but says nothing about the drone, nanotech, or cyber threats. Although it’s unclear whether the resolution is the right vehicle for addressing emerging WMD concerns given a lack of appetite to expand the resolution’s scope, the approach of encouraging countries to adopt legal controls on WMD-related material remains a good one. Similarly, the United States needs to adopt new measures to restrict the proliferation of new, WMD-related technologies, such as requiring new approvals on the production, purchase, and export of pesticide-delivery drones.

The reality is that terrorists do not require WMD to cause major, even existential harm. Terrorist attacks to incite or prevent the de-escalation of a conflict between the United States and China, for instance, may only require a bomb or a well-placed bullet. Moreover, the United States and the global community should not treat WMD terrorism as an isolated threat. Virtually all forms of WMD terrorism require significant financial resources and technical expertise. Degrading, disrupting, and destroying general terror organizational capacity is of tremendous value in reducing the threat.

WMD terrorism remains a serious threat to the country and the globe, but the American approach needs to be aligned with genuine risks to ensure security today and tomorrow.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: COVID-19, bioterrorism, radiological incident

Topics: Biosecurity