One way attack: How loitering munitions are shaping conflicts

By Dan Gettinger | June 5, 2023

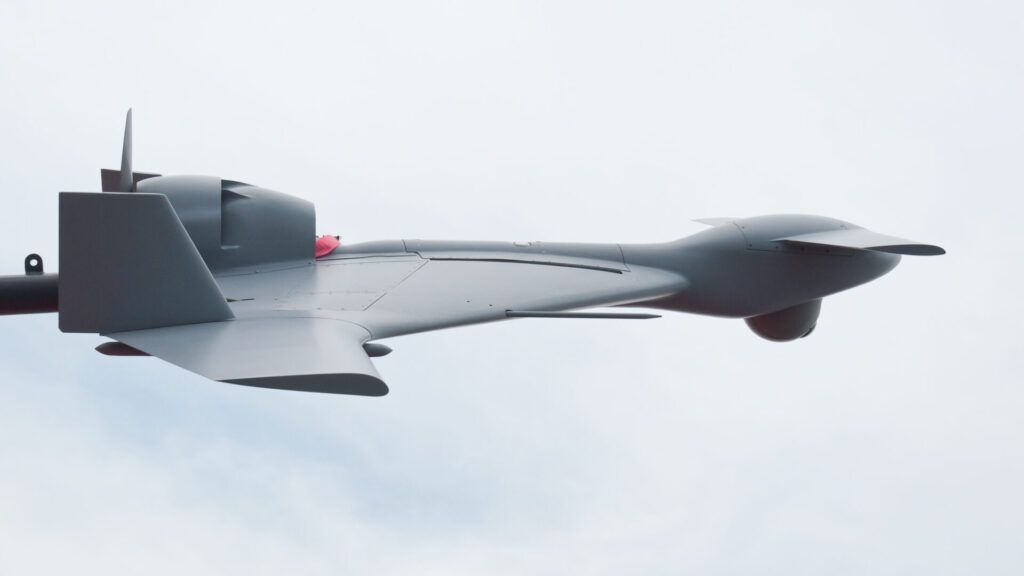

Credit: Julian Herzog, CC BY 4.0

Credit: Julian Herzog, CC BY 4.0

One-way attack drones are an increasingly critical element of contemporary armed conflicts. Nowhere is this more evident than in the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, where Russia’s war of aggression has underscored the many types and uses of these weapons, including the targeting of civilian homes and infrastructure with drones of Iranian origin. Elsewhere, the militaries of countries ranging from Argentina to Estonia have introduced or accelerated efforts to acquire expendable armed drones. These factors have contributed to a dynamic market for one-way attack drones, one that has grown exponentially in recent years.

Evolved from a weapon designed for a narrow mission, one-way attack drones currently play a significantly broader role on the battlefield. The development of one-way attack drones was an integral part of the transition of uncrewed aircraft from the era of high-speed target drones to that of remotely piloted vehicles, one that resulted in a burgeoning marketplace for armed and unarmed drones. The diversification of the marketplace for one-way attack drones and the further integration of these drones into the organization and operations of armed forces suggests a growing function for these weapons in future armed conflicts.

One-way attack drones are a type of expendable drone, one that is typically designed with an integrated warhead and meant to detonate upon target impact. Most one-way attack drones, those known as loitering munitions, can orbit above the battlefield for extended periods until a target is acquired by an operator on the ground or by automated sensors onboard the aircraft. Others are designed to attack stationary targets using pre-programmed directions.

The origins of one-way attack drones can be traced to the early 1970s. Fifty years ago, the US military’s drones were in a bit of a rut. Despite having successfully used drones to conduct reconnaissance missions in the Vietnam War, the Air Force’s jet-powered drones were costly and resource-intensive to operate. Meanwhile, attempts by the Army and Marine Corps in the 1960s to develop smaller, remote-controlled drones for surveillance and target spotting were plagued by technical difficulties.

Inspired by the affordability and usability of remote-controlled model aircraft, the Department of Defense launched a series of projects aimed at producing low-cost drones for the military services. In early 1973, the Defense Advanced Research Agency (DARPA) began working on developing cheap, small drones to attack enemy air defenses. Known as AXILLARY, the DARPA initiative had its roots in a Pentagon-backed project at the CIA, as well as in efforts underway at an Air Force research laboratory.

The AXILLARY project sought to field fleets of low-cost, explosives-carrying drones. These drones would loiter above an area until an adversary radar site began searching for aircraft, at which point the drones would dive into the radar site and explode. Unlike other drones under development at the time, the AXILLARY drones were not meant to be piloted remotely by an operator on the ground, a move aimed at reducing the cost and complexity of the aircraft.

“We don’t want a man in the loop,” Brigadier General Lovic P. Hodnette, Jr., then Air Force director of reconnaissance and electronic warfare, said in testimony regarding funding for harassment drones before Congress in March 1975. “We want to let it go, find a radar and hit it and never come back. We don’t want the manpower, the logistics, to bring it back. It’s a one-way mission.”

Eventually, the AXILLARY project, and the series of programs that succeeded it, failed to produce an operational system, a consequence of both budget cuts and a shift towards a more complex working concept and aircraft design. However, the programs likely contributed to the development of the first commercially successful loitering munition, the radar-hunting Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI) Harpy, in the late 1980s.

Over the next few decades, the role of one-way attack drones on the battlefield gradually expanded beyond the anti-radar mission of the first loitering munitions. In the early 2000s, the emergence of the AeroVironment Switchblade provided special forces units with a portable loitering munition, while the spread of Iranian drones enabled a host of non-state actors to conduct long-range precision strikes. By 2017, a report by the Center for the Study of the Drone at Bard College identified roughly 35 types one-way attack drones of various sizes and capabilities that were in use or development in eight countries at the time.

Since then, the marketplace for one-way attack drones has undergone a dramatic transformation. In a recent survey, the Vertical Flight Society (VFS) found more than 210 types of one-way attack drones, ranging from hand-carried micro drones to those weighing upwards of 300 pounds (150 kilograms). Roughly 87 percent of these aircraft appear to be in some stage of development or active use, the remainder being historical aircraft dating back to the early 1970s.

The Vertical Flight Society survey reflects the shifting dynamics of the marketplace for one-way attack drones. Of the 32 producer countries in the survey, more than half appear to have entered the marketplace in the years since the Bard College report. Prior to 2018, nearly two-thirds of the one-way attack drone systems in this survey were developed or produced in the United States and Israel. In the last five years, as manufacturers in countries like Turkey and China have risen in prominence, just 12 percent of new models of aircraft unveiled in this period originated from the United States and Israel. Between 2018 and 2022, producers in Asia accounted for more than one-third of new models of one-way attack drones.

As the entities and countries producing one-way attack drones have diversified, so has the types of aircraft under development. Until relatively recently, the market for one-way attack drones was dominated by fixed-wing airplanes. Now, however, quadcopters and other types of vertical takeoff and landing drones comprise a growing share—around one-quarter—of the drones in the Vertical Flight Society survey. This trend is driven by demands for more portable systems, as well as for those that could potentially be recovered by an operator.

The precipitous rise in the number of new one-way attack drones has been aided by government-sponsored competitions and acquisition contracts. Multiple countries have launched efforts to develop or acquire one-way attack drones, some with the aim of encouraging the creation of a domestic manufacturing base. In the past few years, drone producers in India, for example, have revealed at least 14 types of one-way attack drones, largely in response to solicitations by India’s armed forces.

The US military is working on around a half dozen projects involving expendable attack drones. According to the Vertical Flight Society study, in its fiscal year 2024 budget proposal to Congress, the Pentagon has requested approximately $622 million for programs involving one-way attack drones, an 85 percent increase over the budget for such drones in fiscal year 2023. Like the market for these weapons, the Pentagon budget encompasses a variety of types of systems and operational needs, ranging from those that could be hand-carried by infantry to those mounted on vehicles and aircrafts. The adoption of these weapons is likely to result in changes in the ways in which some military units are organized and trained, as well as in the creation of units specialized in their use.

Although many of the one-way attack drones currently advertised bear little physical resemblance to those envisioned under the AXILLARY project, the current situation contains echoes of the recent past. One-way attack drones are increasingly viewed as an alternative to the large, multirole uncrewed aircraft. Meanwhile, hobbyist drones, today in the form of small quadcopter platforms, exert a strong influence on the design for new types of one-way attack drones. The armed conflicts in Ukraine and elsewhere have demonstrated the growing reliance many militaries are placing on drones to conduct precise, lethal attacks, one that is likely to be sustained and replicated in the future.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Russia-Ukraine, battlefield, conflict, drones, kamikaze drone, loitering munitions, one-way drone

Topics: Disruptive Technologies