What can we learn from ‘Oppenheimer’ about the blind spots in nuclear storytelling?

By Shampa Biswas | August 8, 2023

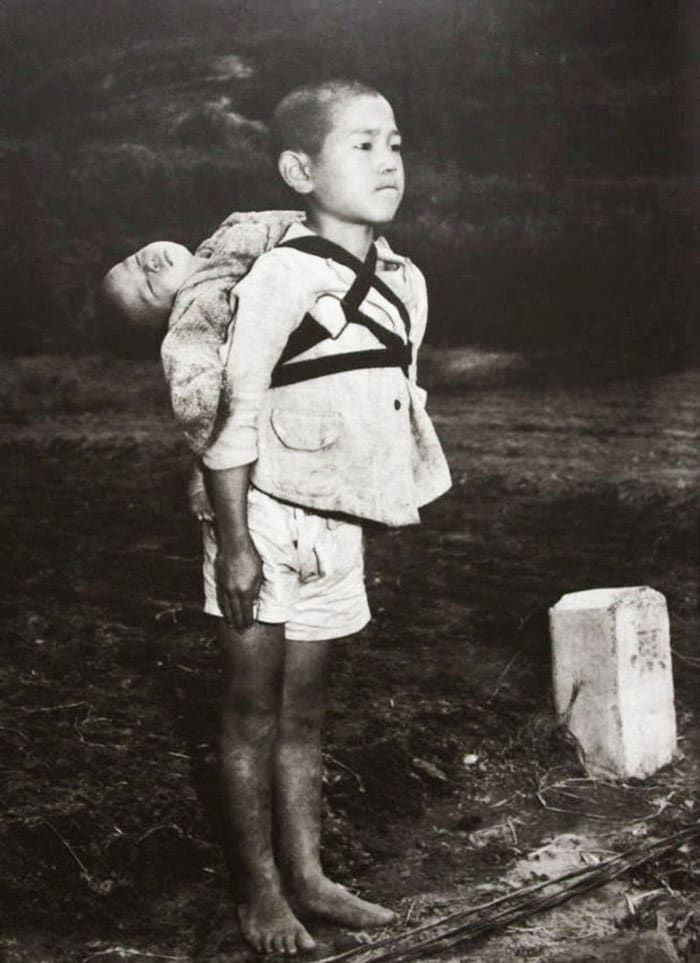

A barefoot boy waiting in line and staring ahead at a crematorium after the Nagasaki bombing, with his dead baby brother strapped to his back. Photo by US Marine photographer Joe O’Donnell

A barefoot boy waiting in line and staring ahead at a crematorium after the Nagasaki bombing, with his dead baby brother strapped to his back. Photo by US Marine photographer Joe O’Donnell

On only two days a year, the site of the world’s first nuclear explosion—codenamed Trinity—is open for a few hours to visitors. Some years ago, I joined an odd group of atomic tourists to make the long trek across New Mexico to visit this iconic site, now made more famous by Christopher Nolan’s film Oppenheimer. What I saw there reminded me of all the stories that don’t make it into most nuclear storytelling.

I had already visited Nagasaki, where the US military used a plutonium bomb codenamed Fat Man, very similar in design and yield to The Gadget tested in New Mexico. Fat Man laid a city to waste, quickly killing between 60,000-80,000 people, the death toll eventually rising to over 130,000. Nagasaki is now the site of an elaborate Peace Memorial whose central story is the victimhood of Japan. It is a deeply moving story, but one told through a nation-making lens, with barely a nod to Japan’s own war crimes or its uneven redressal of the claims of first- and second-generation hibakusha, the surviving victims of the bombing.

The Nagasaki museum tells its heart-breaking story through photographs and objects: dented household pots, ripped clothing, bones of a human hand stuck to a piece of metal, a replica of the destroyed ruins of the Urakami cathedral at Ground Zero, pictures of scarred and dead bodies and a city leveled flat. It is a story that makes you weep for a devastated past and hope for a more peaceful future. Yet one wonders how to make sense of the Japanese government’s embrace of a peaceful future that travels through the contaminating path of nuclear energy, which, after all, is the same path that can quickly take Japan to nuclear weapons. The Fukushima nuclear disaster posed that question anew. The museum provides no answers.

I have also visited Hanford, the site where the plutonium for Fat Man and The Gadget had been produced, which is now home to 54 million gallons of radioactive waste that sit in leaky barrels in what is one of the most contaminated sites in the world. Part of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park, Hanford now hosts a museum that tells a story celebrating its proud contribution to America’s victory in World War II. That story pays no attention to either the devastation of Nagasaki far away or US workers and downwinders profoundly harmed by radioactive exposure in its immediate vicinity.

The Hanford museum tells a story very different in form from the Nagasaki museum, a triumphant patriotic story of technological mastery and industrial genius. Visitors stand awestruck before the graphite core of the spectacular B-reactor or thrill to sit in the reactor operator’s chair. Signs of “danger” strewn throughout the museum are vintage, from a past that now seems contained. Their purpose is to evoke a sense of awe and excitement, drawing attention away from the actual dangers of the high-level radioactive waste that sits so close outside.

I was not surprised that the Trinity national historic site also tells a story of scientific ingenuity and American exceptionalism. But unlike the object-centered stories of Nagasaki or Hanford, what visitors really come to see there is immateriality. A fenced-in expanse of land. A void or an absence. This is the absence made by The Gadget as it scorched and scooped up the earth in its massive fireball and returned it radioactive, in the form of the trinitite that still remains sprinkled all around the site, in and around the crater created by the explosion. At Ground Zero stands a totem-like marker, innocuous and unimpressive up close, yet the climactic point to which the Trinity tour beckons and around which the throngs of tourists eventually collect.

Christopher Nolan’s stunning new film fills this void with the epic story of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Unlike the heroic story about Oppenheimer narrated at the Trinity site, Nolan’s masterful interweaving of different periods of Oppenheimer’s life does not let viewers rest on the triumphant moment of the spectacular Trinity test or leave us simply awestruck at the genius of the scientist-administrator dubbed “father of the atomic bomb.” Instead, we watch the tragedy of Oppenheimer’s life story unfold in the complicated pathways through which hubris and doubt intersect with patriotism and politics to change the course of history toward the most dangerous of futures. Nolan tells a complex story, neither celebratory nor heart-wrenching.

And yet even this remarkably well-told story leaves little space to mourn or honor the tragedies of other lives devoured by the bomb. Japanese victims appear in the film as no more than the hauntings of a man troubled by his celebrated role in the making and use of the bomb. Those lives and futures decimated by fallout downwind of the Trinity test find no reckoning at all. Nor, for that matter, do the lives lost and impaired through the 1,029 nuclear tests conducted by the US alone that followed the Trinity test, most on colonized and indigenous lands.

Indeed, there is little to remind us in most of the stories we tell about the bomb that nuclear weapons are dangerous not just when used in war, but all through their cycle of production and testing. And the heaviest toll of that cycle has been paid by ravaged brown and black bodies.

The start of the production cycle for the bombs dropped in Japan is in Shinkolobwe, a settlement in the Katanga province in the Democratic Republic of Congo. This is where most of the uranium for The Gadget and Fat Man was mined, to be turned into plutonium at Hanford. That mining occurred under the excruciatingly brutal conditions that constituted Belgian colonial rule in Congo. Over time, Shinkolobwe’s rich reserves of uranium ore attracted the invasive attention of Britain, France, Germany and the United States, leaving behind a history of death and diseases contracted from radioactive contamination. Formally closed in 2004 and now an unglamorous wasteland, Shinkolobwe—unlike Nagasaki, Hanford or Trinity—houses no monument or museum. The darkest victims of the nuclear production cycle find neither commemoration nor reparation. No epic film remembers their stories.

We will be well served if Oppenheimer instigates a much-needed public conversation about the dangers of nuclear weapons. We will be better served if the stories we tell about those dangers include the full breadth of nuclear harms and attend to those made most vulnerable by nuclear weapons production, testing, and use.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Fat Man, Hanford, Hiroshima, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Katanga, Nagasaki, Shinkolobwe, The Gadget, Trinity

Topics: Nuclear Waste, Nuclear Weapons

The author fails note the abusive, racist, and sexist culture of Imperial Japan and its history of genocide and colonialism. Her historical analysis (or lack thereof) is an inch deep, at best.

My father was involved with early nuclear testing from 1948 to 1953. He was one of the soldiers exposed to radiation. He died in 1967 of multiple cancers. All claims made by my mother were denied by the government.

My parents, an aunt, two uncles, and 7 cousins in NM died of cancers after exposure to the radioactive cloud from Trinity over Lincoln Co., NM, in 1945. Secrecy trumped safety in this case. I advocate for truth telling and a redress of grievances as assured by the First Amendment. My grandson is an incoming freshman to Whitman! Of course, he is only learning about our family’s trauma.

Thank you. I find the film glaringly sanitized as concerns the reality of the massacre of the civilian populations of two cities in horrific “inhuman” ways. Who care abouts Oppenheimer’s sex life, when all we see, as you said, is a view of him viewing the horrific effects of these bombs. Enough already! 78 years of silence on this inhuman massacre on the part of the US Military; and this is the best we can do???? The US has NEVER taken responsibility for the massacre, and has never been held accountable, despite the toiling and unflagging efforts of those scientists… Read more »