The climate blind spot in nuclear weapons policy

By Cameron Vega | November 2, 2023

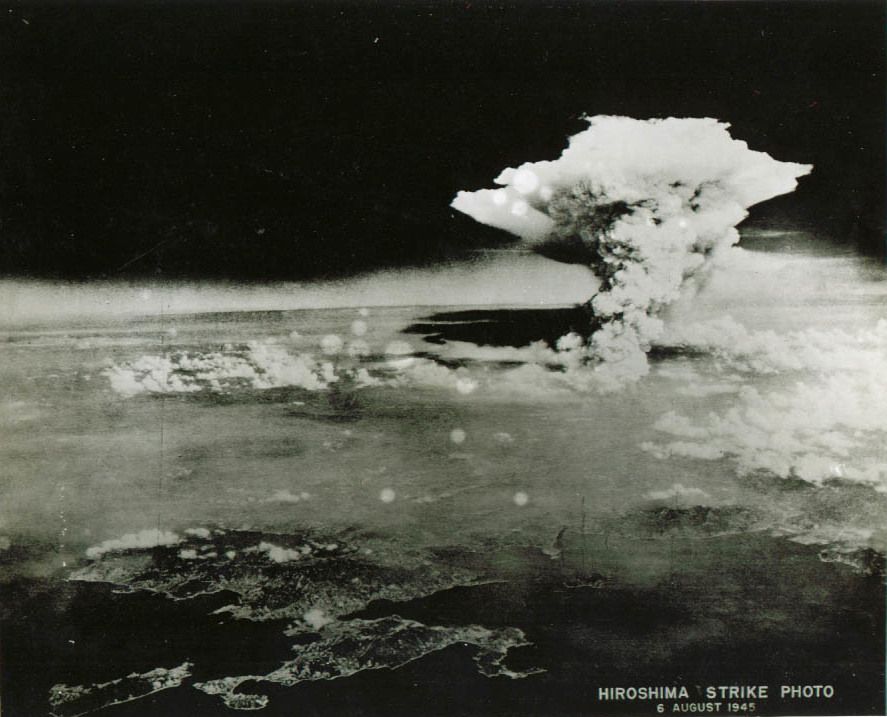

Massive fires set off by the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, in 1945 created this enormous cloud photographed a few hours after the explosion. Climate models predict that a nuclear war would send huge amounts of soot into the atmosphere, blocking sunlight and causing global food insecurity and famine. Credit: US Army

Massive fires set off by the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, in 1945 created this enormous cloud photographed a few hours after the explosion. Climate models predict that a nuclear war would send huge amounts of soot into the atmosphere, blocking sunlight and causing global food insecurity and famine. Credit: US Army

The world-ending potential of nuclear weapons looms over populations around the world. Climate change is a slower-moving catastrophe, but it openly threatens every community. Although younger generations are focused on climate change as the biggest threat, these two existential crises are intrinsically linked. Understanding their connection can lay the groundwork for alleviating the threat of a nuclear war and the cataclysmic climate event that would follow.

Nuclear weapons in the United States are governed by more than just law and policy—a system of ethics underpins how they may be used and for what reason. Nuclear ethics are at the core of any nuclear strategy and serve to inform decision making about how to grapple with the reality of an apocalyptic class of weapons. The field retreated after the end of the Cold War, but the ever-present use of nuclear blackmail by Russia against Ukraine and its allies, and a looming Chinese buildup of its nuclear arsenal, are bringing nuclear ethics back to relevancy in the United States. Increasingly divorced from the logic of the Cold War, the new generation of nuclear ethicists is seeking a nuclear strategy that can break free from the restraints of deterrence—its tendency to drift toward misinterpretation, its mistaken belief that an adversary mirrors one’s own assumptions and decision making, and its reliance on cooler heads prevailing during nuclear scares.

Climate science must be an essential component of the effort to reinvent nuclear ethics. The US government has persistently failed to consider the climate effects of nuclear weapons in its policies, ignoring studies that draw attention to the scientific reality of nuclear winter and the devastating famine that would follow. If policy will not acknowledge this risk, ethics should lead the way. The latest climate science has massive implications for nuclear ethics and should be a focal point in future discussions about what an ethical nuclear posture looks like as nuclear ethicists seek to recapture their relevance and steer nuclear strategy in a more ethical direction.

The failure of policy. The 2022 US National Defense Strategy makes clear that climate is a major issue for national security. Climate change is a conflict multiplier and a threat to military bases, and the Pentagon is the world’s biggest single emitter of greenhouse gases. This emphasis on climate change in the most public-facing military strategy of the United States is a radical shift from previous national defense strategies.

The National Defense Strategy is accompanied by two other major pieces of strategic review: the Nuclear Posture Review and the Missile Defense Review. All three are developed together and collectively form the basis of American military strategy. But although the Nuclear Posture Review is meant to reflect the broader principles of the National Defense Strategy, it contains no references to climate or the environment.

This is not an accidental oversight. The United States has historically paid little attention to the climatic impacts of nuclear weapons. Since the late 1940s, the Defense Department has underestimated the damage a nuclear weapon could cause through fires and debris, which not only underplays the overall impacts of nuclear use but also reduces estimates of atmospheric soot, which is the primary cause of nuclear winter—a phenomenon in which soot from nuclear explosions would blot out the sun.

In addition, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, where the United States is a first among equals, stifled panel discussions and workshops on climate change in the 1980s. The US government’s persistent failure to account for the potentially devastating climatic effects of nuclear weapons stems from an unwillingness to re-examine conventional thinking about nuclear strategy and use.

The latest climate science. The potential for severe climatic damage through nuclear use is not a new discovery. As early as 1949, scientists sought to measure the interplay between nuclear weapons and meteorology through Project GABRIEL, an attempt to gauge the likely impacts of fallout from a nuclear war. Climate science developed as a field in the following decades and eventually became a public affair, as knowledge about the greenhouse effect grew in the 1970s. By the 1980s, nuclear winter entered the limelight with a landmark paper on nuclear winter by atmospheric scientist Richard Turco and colleagues. Today’s climate science—using faster computers, better understanding of the atmosphere, and data from recent forest fires—confirms that nuclear war would cause global climate change.

In 2022, a team led by Rutgers atmospheric scientist Lili Xia brought together decades of research and reported that soot injected into the atmosphere by nuclear war would cause global food insecurity and famine. The team calculated that a one-week nuclear war between India and Pakistan could kill more than 2 billion people. In a simulated all-out nuclear war between Russia and the United States, the estimated deaths from starvation would surpass five billion. In each case, it would take Earth’s climate more than a decade to recover.

Historically, climate science on nuclear winter has been limited by the uncertainty inherent in modeling the makeup of the soot, its distribution, its properties relating to the absorption and dispersal of sunlight, and the amount of soot generated from ground versus air bursts. Nuclear war also contains unknowns, primarily related to targeting. Despite these uncertainties, different models have consistently predicted nuclear winter as an outcome of nuclear war, and studies continue to grapple with the potential consequences.

The implications for nuclear ethics. Climate science has several major implications for nuclear ethics. All impact the underlying logic and morality of deterrence.

First, excluding climate science from nuclear ethics—and by extension, nuclear strategy—is dangerous. The idea that ethical reservations weaken deterrence by encouraging adversaries to believe that an ethical government would hesitate to respond to a nuclear strike is a misleading one. If the intention of nuclear deterrence is to produce a safer, more stable international system, then denying the devastating climatic effects of nuclear war is counterintuitive. One of the core tenets of deterrence is the willingness to use nuclear weapons if push comes to shove. If nuclear winter elevates the cost of nuclear use, then deterrence may be strengthened, because adversaries may perceive their ability to survive a famine-inducing nuclear exchange as near-zero. However, if nuclear winter makes the use of such weapons untenable on a global scale, deterrence may not be a suitable posture for mitigating nuclear war because the cost of a mistake or accident rises exponentially once nuclear winter is taken into account.

Second, the latest climate science heavily implies that there is a soft cap on the number of high-yield warheads that can be detonated in nuclear conflict before the smoke and debris cause a global famine. This soft cap should place restrictions on nuclear war scenarios and nuclear targeting, which has been further complicated by evidence that China is seeking near-parity with the United States and Russia. A soft cap also weakens arguments for nuclear superiority. Additional nuclear weapons, either from expanded arsenals or Chinese parity, cannot feasibly achieve more than marginal destructive gains over a period of around 10 years (the minimum amount of time for the planet to recover from nuclear winter), even if additional nuclear use produces more immediate results.

Third, as a result of this soft cap, even though a unilateral nuclear strike could cause global famine, retaliation would further exacerbate that famine. Retaliatory self-defense is a just but limited cause, so nuclear ethics must come to grips with the climate costs of retaliation. Second-strike capabilities will remain an essential aspect of nuclear force structure, but the logic of an immediate and definitive retaliatory strike should be weighed against the global reduction in food production. Climate considerations should not altogether rule out nuclear retaliation, but the failure to consider how a retaliatory strike can generate further, long-lasting harm to survivors would undermine decision making in a crisis scenario. This potential weakening of retaliation, though uncomfortable, is an important consideration in the current debates over the justice of deterrence.

Finally, the extent of climate damage caused by nuclear weapons raises a critical question about the doctrine of double effect, which argues that an intended action with an ethical primary effect is permissible even if it has an unethical secondary effect. For example, the insistence of the United States that it does not target civilian populations with nuclear weapons, despite the fact that civilians are likely to be killed in the event of a nuclear strike, means that a counterforce nuclear strike could be deemed ethical so long as the secondary civilian deaths were proportional to the counterforce effects. However, the secondary effect of global famine and devastating local damage to the water, soil, and air around a detonation site has a significant impact on proportionality. Without considering the climatic effects of nuclear weapons, any calculation of the ethical merit of a nuclear strike through the doctrine of double effect is incomplete.

The implications of incorporating climate effects into contemporary discussions about nuclear ethics go beyond the four outlined above. Acknowledging the devastating potential of nuclear winter does not make nuclear weapons more dangerous; instead, it shines a light on what these weapons were already capable of doing. What is dangerous is excluding climate science from nuclear ethics because it is inconvenient or hard to grapple with.

If the possibility of nuclear winter leads to a reevaluation of deterrence as an ethical and practical posture, then nuclear ethicists should lead the way in replacing an outdated strategy.

Editor’s note: This work was supported by a fellowship from the Federation of American Scientists. The author thanks Alan Robock for his mentorship and valuable suggestions on this article. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the views of the US State Department.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Nuclear Posture Review, nuclear ethics, nuclear winter

Topics: Climate Change, Nuclear Risk, Nuclear Weapons, Voices of Tomorrow

The very premise of this article is an oxymoron when it states ” climate science…can help steer nuclear strategy in a more ethical direction”..? You are talking about weapons of mass direction in the same sentence as ethics /ethical direction which is absurd. The end game here negates climate science and all talk of progress pertaining to it.

Thank you

As a young man living the Marshall Islands- a country that suffer a lot from these two major issues which are climate change and nuclear impacts, I really hope that all these developed countries upholding all these continued usage of Nuclear Weapons, and continually contribute to worsen our climate (given the current status of our home after multiples attacks of climate change through sea level rise), will take to reconsideration about the safety of our home and the well-being of our people. My people, especially our elders who have passed this life due to nuclear impacts such as health issues… Read more »

I applaud you bringing the topic of nuclear winter to the table. Originally I believe Carl Sagan brought this issue up in the 70’s. In addition to the direct effect to the climate there is in my opinion another destructive effect that is indirect. The money, time and resources that are spent on nuclear weapons could have been used on climate change mitigation. When the ledger is opened and the tally is made the loss of those resources might be the ones that pushed us over the tipping point into run away extinction from climate change.

While I appreciate and agree with integrating climate change considerations into nuclear weapons policy, I question the angle of ethics here. Part of the problem is that the development and maintenance of nuclear weapons have been, and continuous to be, unethical from an environmental standpoint, given the significant contamination from nuclear weapons facilities and the ways in which these contaminated spaces already pose significant climate risk (e.g., concerns about the Runit Dome and what water acidification / rising sea levels would do to this structure). I think the piece about nuclear winter and its impact on nuclear deterrence is valuable,… Read more »

An excellent take on a crucial, timely topic.

One disparity between the nuclear winter (NW) discussions surrounding the original TTAPS paper in the ‘80s and today’s iteration bears scrutiny: Governments then, including the US and the Soviets, engaged in public dialogues on NW, while today, with decades of improved analysis and greater understanding, governments are silent on the topic.

Is it because the Big Nuke cartel recognises NW as it’s death knell?

“Exhibition A” that’s what I have called the firestorm photograph at the top of this important article. While working for the City of Hiroshima, I calculated the height of this “cloud”: 22 kilometers. It has reached and breached the tropopause, provide proof positive that nuclear-ignited firestorms can inject soot above rain clouds where self-loafing by sunlight keeps it up for decades.

The Peace Memorial Museam had incorrectly captioned a wall-sized version of this photo as the “mushroom cloud.” This has since been corrected.

(I will have more to say about the article, tomorrow.)