Picturing the invisible: Legacies of Fukushima in art

Twelve years after the Great East Japan earthquake, tsunami, and reactor meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, the triple disaster’s effects are still keenly felt. Even today, hundreds of workers labor to decommission the nuclear plant—a task expected to take another 30 years and $96 billion. Many more work to decontaminate the surrounding countryside, slowly reducing the area of land declared unfit for human habitation.

The government’s enthusiasm for lifting evacuation orders is not shared by many Fukushima residents. More than two thirds of the approximately 160,000 people forced to evacuate their homes after the March 11, 2011 disasters now have permission to return. Only a minority have chosen to do so—and most returnees are old. Residents of Yamakiya, for example, estimated that less than a third of the village had returned and around two thirds of those were aged 65 or older. Whatever their reasons, the outcome is the same: The affected territories are aging rapidly, even by the standards of a super-aging society. The reconstruction of Fukushima thus remains an active policy issue for Japan today.

Current events have also breathed new life into the memory of the Fukushima disaster. Fears of another nuclear disaster have been fanned by the war in Ukraine—Russia’s seizure of Chernobyl caused a degree of alarm which was quickly surpassed by the occupation of the Zaphorizhzhia nuclear power plant. At the same time, the war also exposed Europe’s reliance on imports of Russian gas, prompting Germany to debate the wisdom of its nuclear moratorium—a decision taken in direct response to the nuclear disaster in Fukushima. Even half a world away, politics remains haunted by the events that began on March 11, 2011.

“Picturing the Invisible” is a traveling exhibition that examines the realities of life in the wake of the triple disaster. The exhibition brings together nine talented artists, working with photography and film in the affected territories, to examine the lingering legacies of “3/11.” Their work, some of which is presented below, captures both the spectral presence of radiation and fingerprints left by the disaster on Japan’s collective psyche. Using the power of art to inspire, entice, and seduce, the exhibition aims to create a space to discuss the multifaceted legacies of the nuclear disaster, beyond the often binary exchanges between nuclear advocates and nuclear detractors.

March 9, 2023

Art by Takashi Arai, Rebecca Bathory, Thom Davies, Masamichi Kagaya, Satoshi Mori, Yoi Kawakubo, Giles Price and Lieko Shiga

Design by Thomas Gaulkin

Editors note: “Picturing the Invisible” has been exhibited at the Royal Geographical Society, London (October-December 2021), Technical University Munich (June 2022), and is now on view at the Heong Gallery, Downing College, Cambridge until April 23, 2023. All of the artworks, along with paired essays by experts, policymakers, authors, and activists, are available at the exhibit website.

Lieko Shiga, “Blindfolded Pilot,” from the Rasen Kaigan (Spiral Shore) series (2010)

Taken three months before Japan’s triple disaster, this photograph by Lieko Shiga is a survivor. Unlike other artists who were drawn to the area afterward, Shiga was already living in the coastal village of Kitakama in Miyagi Prefecture, just north of Fukushima. She was producing a new body of work, titled “Spiral Shore,” when tragedy struck.

On March 11, 2011, Northeast Japan was hit by a Richter scale 9.0 earthquake—15 times more powerful that the earthquake that devastated Turkey and Syria last month, and around 60 times as powerful as the 1995 Kobe Earthquake. While Japan’s infrastructure weathered this seismic shock well, it was devastated by the tsunami that followed. Reaching heights of 40 feet, the tidal wave penetrated six miles inland and destroyed more than 100,000 homes across the Tohoku region. Kitakama residents were among the almost 16,000 declared dead. Shiga’s studio was destroyed and many of her works were lost—but this photo survived.

So did many others. As volunteers cleared the debris of more than 123,000 levelled homes, they picked photographs from the rubble and took them to community centers. Shiga noticed that the photos brough to her local community center were damp, dirty, and starting to go moldy. She committed herself to cleaning and cataloguing them, identifying their subjects, and working to return them to their rightful owners. Many were delighted to be reunited with their family photographs. Others asked Shiga to throw them away. The photos were changed by the waves, and were now reminders of lives and livelihoods lost forever.

Shiga’s work too was transformed. When the Spiral Shore was published in 2012, few could look upon her flamboyantly expressive images without dwelling on how the very coastline that served as her canvas would soon be struck by 40 feet of water. In this light, the spirals that Shiga traced into the shore seem almost prophetic—somehow prefiguring the disaster to come, in which entire buildings were swept away as surely as lines in the sand.

Takashi Arai, “A Mirror on the Other Side, Maquette,” (2021)

Takashi Arai uses a 19th-century technique to depict a 21st-century subject in this image of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. The 2011 earthquake and tsunami caused the loss of power to three reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi plant, damaging the electricity grid and disabling 12 of 13 backup diesel generators that were located on site. In turn, this caused the plant to lose the ability to cool theses three reactors, which experienced meltdowns over the next three days as an anxious nation watched. Fukushima was thus seared into Japan’s collective psyche.

Memory is at the heart of Arai’s photographic practice. More than two decades ago, Arai decided that his path to mastering analogue photography would involve tracing the historical evolution of the medium. He never moved beyond the daguerreotype. Popular in the 1840s and 1850s, a daguerreotype is an image produced on a silvered copper plate. Studying and experimenting with the process since 2002, Arai has found the daguerreotype to be an ideal format for examining our collective memories of the nuclear age. Like a memory, the image is not easy to grasp, and requires work to see clearly. And the polished silver of the daguerreotype is a reflective surface, which imbricates the viewer with its subject matter – an apt metaphor for the ways in which we distort our recollections, imposing onto them elements of our present selves. In Arai’s hands, this old technique is given new life, used to photograph sites of collective memory, like the Hiroshima memorial, Lucky Dragon 5, and the fields of Fukushima.

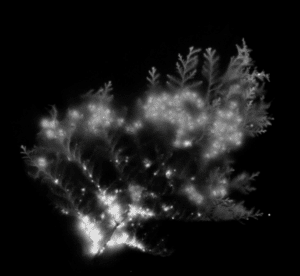

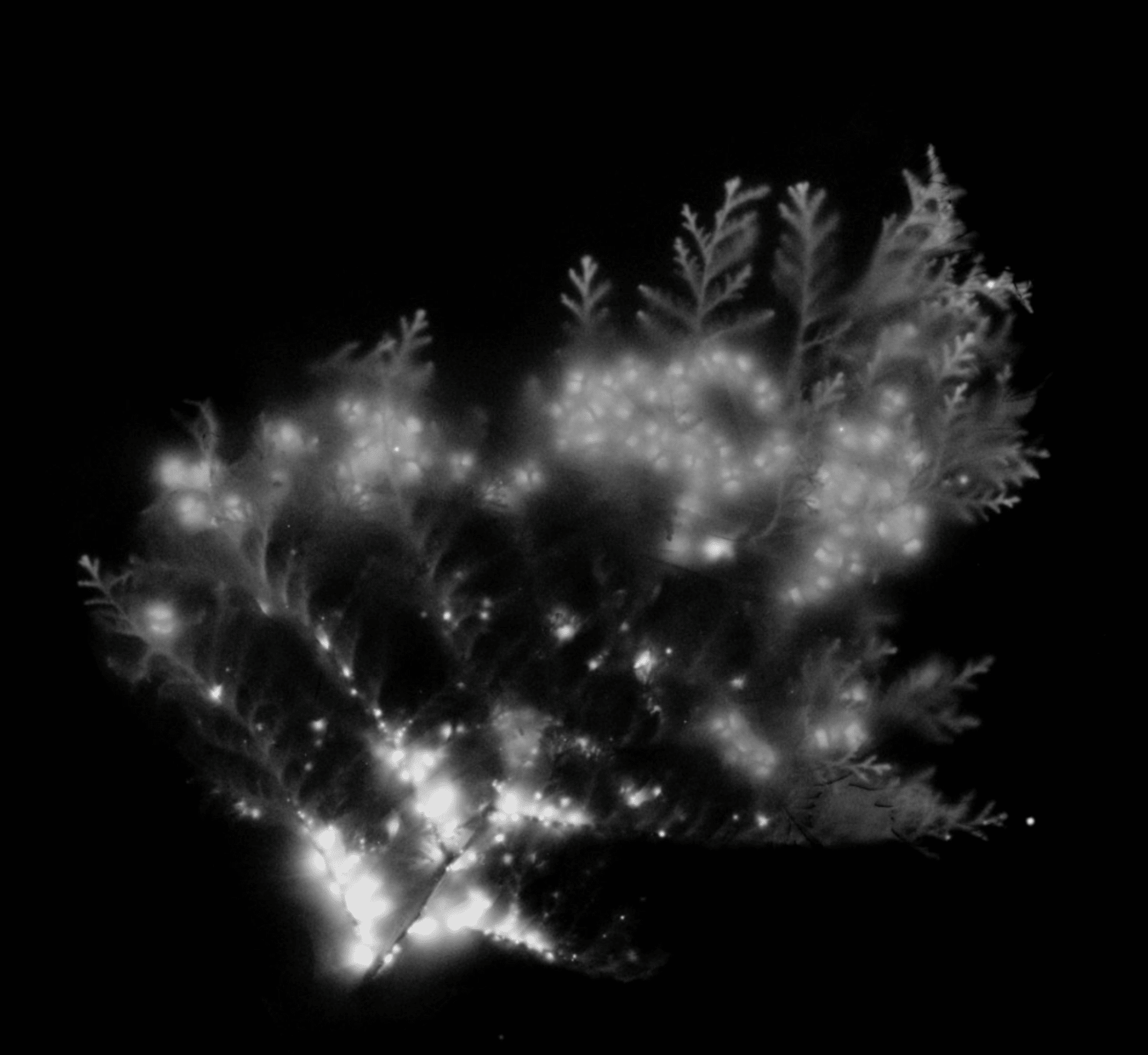

Satoshi Mori (with Masamichi Kagaya), “Cypress Leaves,” from the Autoradiograph series (2014)

Autoradiographs are films exposed to radiation instead of visible light. Using this technique, photographer Masamichi Kagaya and Satoshi Mori resolved to picture the invisible, revealing the contamination of everyday objects taken from Fukushima prefecture. These works literally picture radioactivity—the more radiation emitted, the brighter the spot. The result are images that look like especially neat constellations. And like the stars, these images can be read, yielding clues about patterns of contamination. For example, why does this cypress leaf—taken from Iitate village, some 35 kilometers away from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant—oscillate between areas of higher and lower contamination? And what might this tell us about how contaminants have been dispersed and taken up by the tree? In revealing these otherwise hidden patterns, Mori and Kagaya shed new light on the fallout of the 2011 nuclear disaster.

Masamichi Kagaya and Satoshi Mori, “Evacuation: Insoles,” from the Autoradiograph series (2018)

The release of large quantities of radioactive material from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant led the Japanese state to declare a mandatory evacuation zone, deemed unfit for human habitation. Titled “Evacuation: Insoles”, this work by Kagaya and Mori was produced by placing shoes—left behind in evacuated villages for more than six years— onto a radiosensitive plate and evokes the scale of the displacement caused by the Fukushima Daiichi disaster. As the exclusion zone expanded, more than 160,000 people were forced from their homes. Entire towns were abandoned, including Futaba and Namie, from which the shoes used to make this image were taken. Collected with residents’ permission over the course of a year, these shoes are as diverse as their owners. Some are high-heeled. Others belong to children. All are contaminated to vastly varying degrees—sometimes even the right and left shoe have been contaminated to different extents.

The pleasing arrangement of shoeprints creates the impression of an impressively orderly evacuation. The realities on the ground were more complicated. In the first 48 hours of the disaster, Japan evacuated a two, then three, then five, then 10, then 20 km radius of the Fukushima Daiichi power plant. But the upheaval did not end there. A month later, the state began defining the exclusion zone by levels of environmental contamination rather than distance. Some families were evacuated multiple times. Others discovered that they had evacuated into more highly contaminated areas: distance from the power plant proving a poor heuristic for how contaminants were dispersed by the wind. And the act of evacuation itself sometimes proved fatal. Of the 338 patients at Futaba Hospital, located less than 5 km from the Fukushima Daiichi plant, 39 died during the evacuation—their care disrupted with mortal consequences.

Other Fukushima residents found life as an evacuee intolerable. In August 2014, the Fukushima District Court ruled that the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) was responsible for a 58-year-old woman’s suicide. Having fallen into a deep depression after being evacuated from her home 40 km from the nuclear plant, Hamako Watanabe returned to her home in July 2011, soaked herself in kerosene and set herself ablaze. Tragically, her story is not an isolated one. Suicide rates rose in evacuated populations several years after the disaster. Fukushima’s footsteps shine brightly, but they walk through darkness.

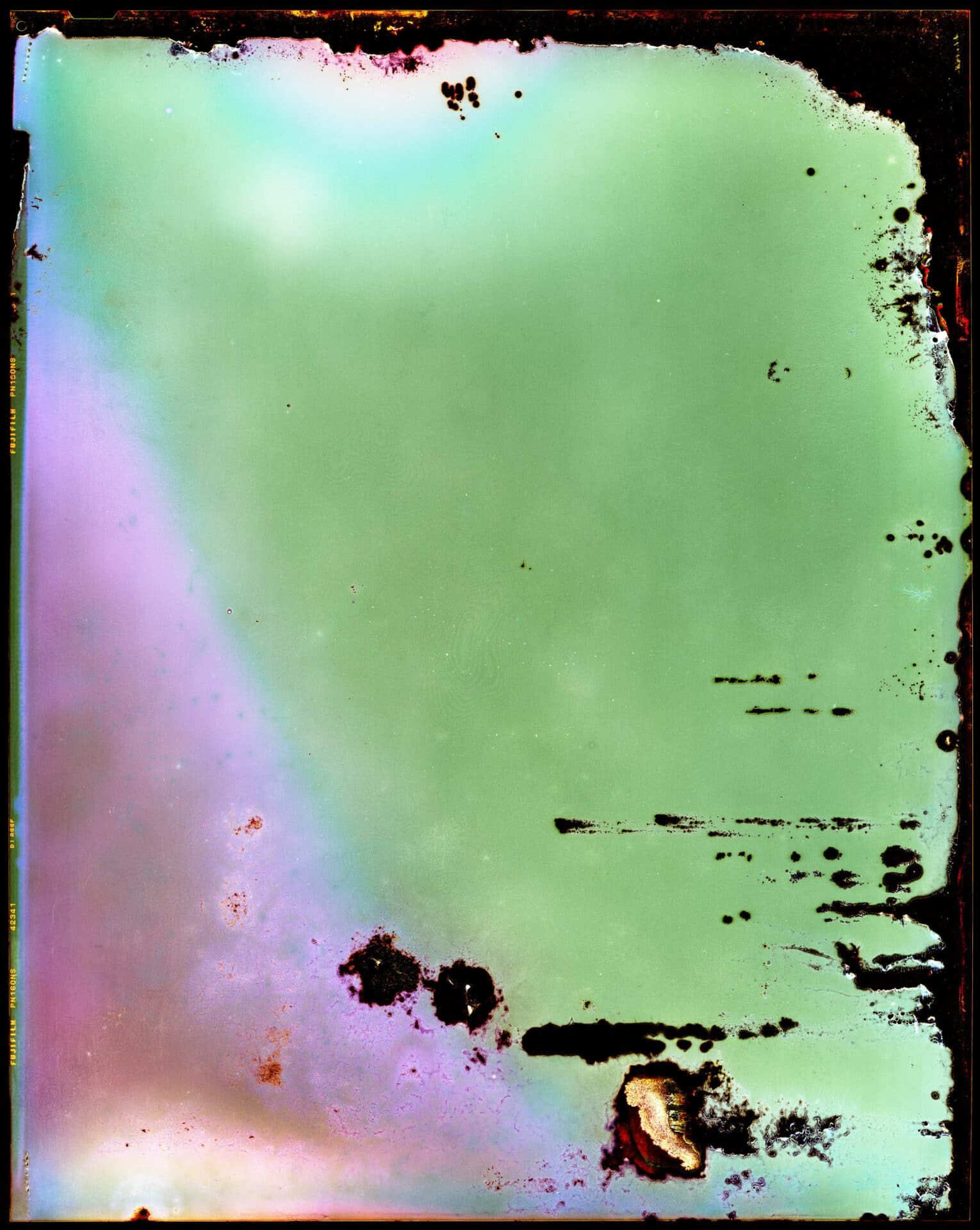

Yoi Kawakubo, If the Radiance of a Thousand Suns were to Burst into the Skies at Once, IV (2019)

To produce this abstract image, artist Yoi Kawakubo donned personal protective equipment and ventured into the exclusion zone, burying large format Fuji Film into the contaminated earth. He returned months later to disinter and develop it. Most of the buried film was corroded or completely overexposed. But in other cases, like this one, the ghostly touch of radiation remained visible.

Kawakubo titled this series “If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst into the skies at once,” a quote from Hindu scripture and an allusion to the dawn of the nuclear age. J. Robert Oppenheimer ("father of the bomb") famously explained that as he looked upon the successful detonation of the "Gadget" nuclear device at the Trinity test site, he recalled a line from the Bhagavad Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” But in earlier recollections, Oppenheimer mentions another line too, from which the artist takes his title: “If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst into the skies at once, that would be the splendor of the mighty one.”

The enlargement pictured here is, in fact, nearly two meters tall. Viewing it, one feels a sense of awe, and perhaps even a little small before the mystery, beauty, and terror of the nuclear sublime.

J. Robert Oppenheimer as recorded for the 1965 NBC television special, "The Decision to Drop the Bomb." (Atomic Archive)

Rebecca Bathory, from the Return to Fukushima series (2016)

They may seem innocuous, but the black bags piled high in Rebecca Bathory’s photograph are instantly recognizable to any Fukushima resident. Filled with radioactive soil, these flexible containment bags are a product of Japan’s decontamination efforts. In the years after the disaster, tens of thousands of workers removed soil and other irradiated material in order to lower levels of environmental radiation in evacuated areas and expedite residents’ return. Topsoil was scraped into these one-cubic-meter containers, which are usually stacked four-high, before being covered with uncontaminated soil and a waterproof sheet. The result is a tarpaulin-wrapped mound that towers over even the tallest passerby.

By 2015, more than 9 million such bags had accumulated, spread across 100,000 plus “temporary” storage sights. Japan’s government has pledged to dispose of the soil at a permanent location outside Fukushima prefecture by 2045, but the search for appropriate sites is still ongoing. In the meantime, the bags remain a complicated sight for Fukushima’s many farmers: The bags are a byproduct of a process that has allowed residents to return to areas of Fukushima, but are filled with the topsoil that their blood and sweat once fertilized.

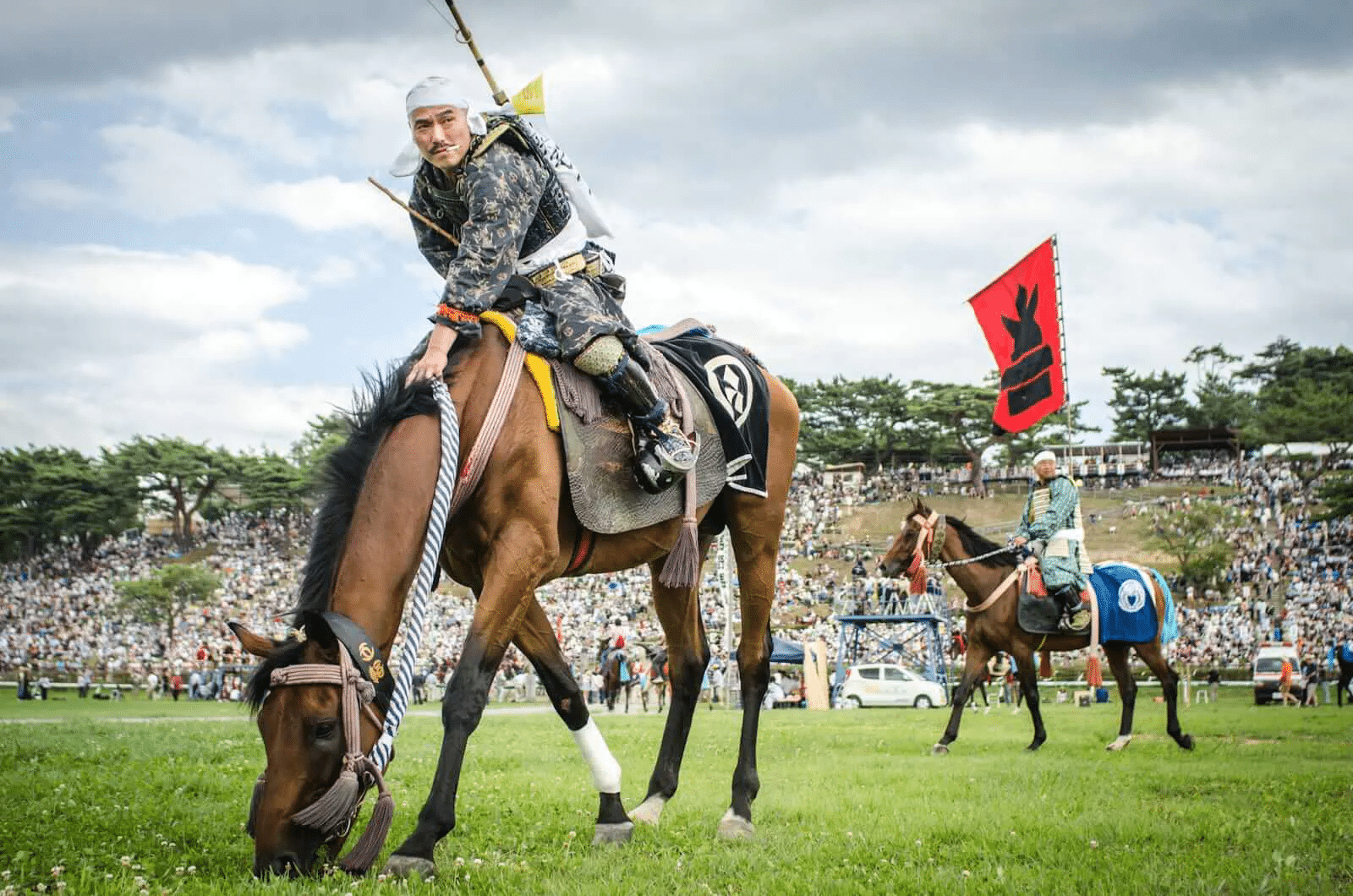

Thom Davies, from the Nuclear Samurai series (2014)

No tradition is as closely associated with the effort to rebuild Fukushima as the Soma Nomaoi Festival. Held every July, the festival sees 400 residents—mostly male—don samurai attire and compete in races and other mounted games over the course of three days. Dating back at least as far as the 13th century, the festival was cancelled in 2011, but resumed to widespread acclaim in 2012.

For many, the mounted horsemen are the “samurai spirit” of the region made manifest, unbowed and unbroken by the triple disaster. For the photographer, Thom Davies, the festival offers an opportunity to question the (gendered) stories and images we use to discuss disasters. Davies is fascinated by our collective tendency to celebrate a certain mode of masculinity: stoic and willing to self-sacrifice, epitomized by those members of the military and TEPCO who volunteered to venture into the flames of the Fukushima Daiichi power plant to contain the disaster. These members of the so-called “Fukushima 50” frequently found themselves stylized as “nuclear samurai” by the international press—a phrase appropriated in this work’s title.

Women from Fukushima prefecture have been left out of the picture in other enduring ways. For instance, in the aftermath of the nuclear disaster, conflicting views about the safety of the decontaminated territories led some married men to return to work in reopened areas by themselves, leaving their wives and families behind as evacuees. Breakups became so common as a result that the phenomenon was given a name: genpatsu rikon, or “atomic divorce.”

Davies’ photographs of the “nuclear samurai” do not deny the incredible bravery of the first-responders. Nor do they mute residents’ enjoyment of the Nomaoi Festival. They seek only to ask who (and what) is left out when we focus the stories we tell about Fukushima on both professions and festivals that are dominated by men.

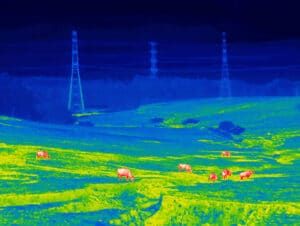

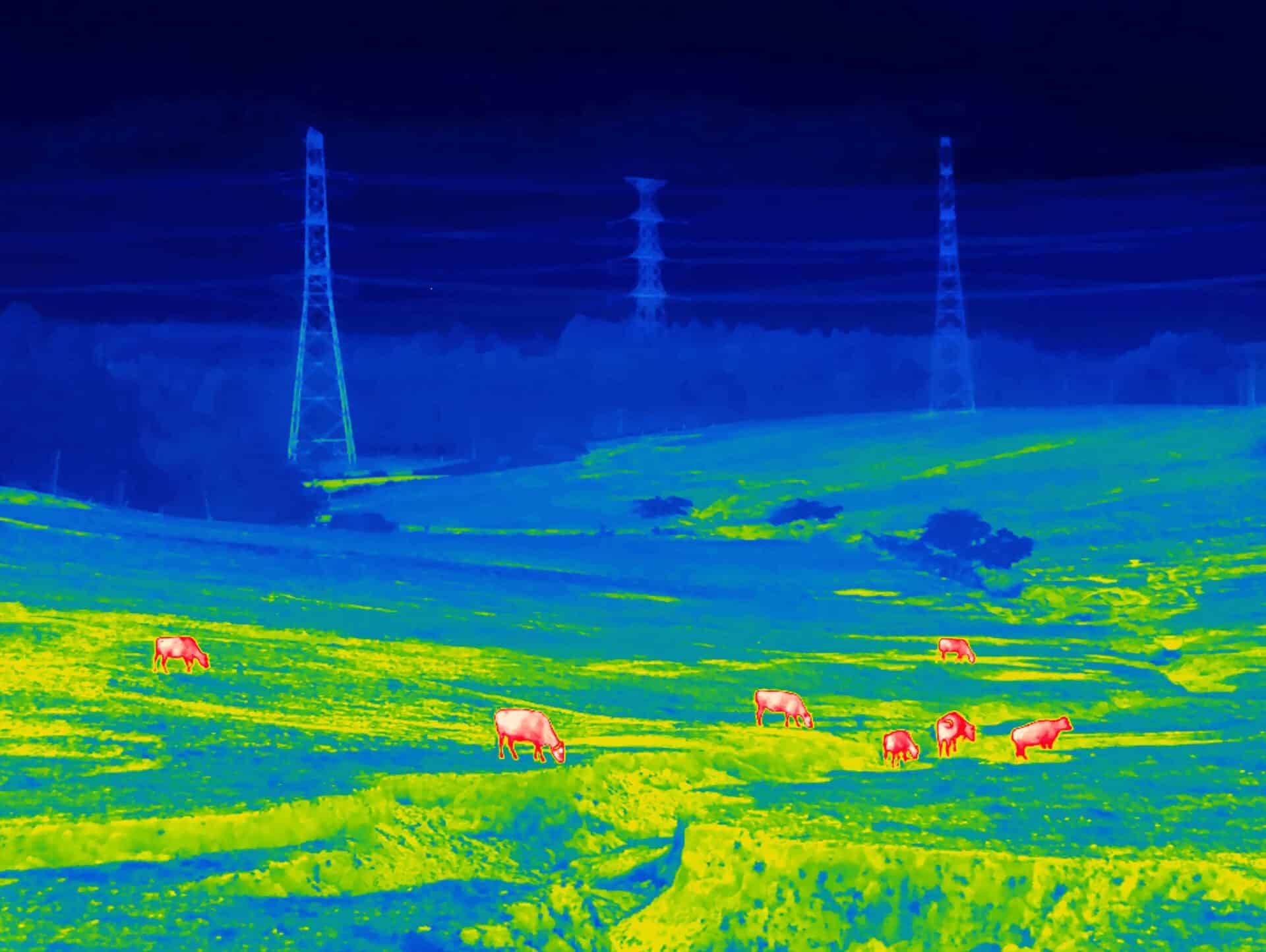

Giles Price, from the Restricted Residence series (2017)

In his “Restricted Residence” series, Giles Price focuses on the psychological experience of nuclear disasters, offering a distinct take on the theme of “picturing the invisible.” Using thermal imaging, Price renders eerie the landscapes of Namie and Iitate: two heavily contaminated villages in Fukushima Prefecture, both evacuated for six years.

When the Japanese state began to incentivize villagers to return in 2017, it met stiff resistance. Some were concerned about the adequacy of Japan’s safety standards. Others had simply settled into new lives. Still others were deterred by the harsh economic realities that they would face back home.

As Price’s photograph of cattle grazing reflects, agriculture is a significant source of employment in Namie and Iitate. Despite the Japanese state’s efforts to tighten food safety standards, few customers want to buy food “made in Fukushima.” At the time that Price was producing his series, almost 20 percent of Japanese citizens living outside the stricken prefecture reported that they were still avoiding food from Fukushima. This number has declined over time (it was once as high as 30 percent and had fallen to 15 percent by 2019) but many items of Fukushima produce continue to command lower prices than they did in 2010—a phenomenon that the Japanese state has labelled “reputational damage.”

By bathing the cattle pasture in lurid greens, blues, and reds, Price evokes how dramatically an unseen contaminant has transformed our relationship to the fields of Fukushima and their fruits.

Giles Price, from the Restricted Residence series (2017)

Giles Price’s interest in toxicity stems from his own experience of the Persian Gulf War, in which he was exposed to chemical agents. Medically discharged from the British Military, Price went on to receive a formal training in photography, where he encountered the work of Eugene Smith and Aileen Mioko Smith in Minamata, a small fishing village poisoned over decades in the mid-20th century by mercury released from a nearby chemical processes plant. In this work (paired in the exhibition with an essay by Aileen Smith), Giles depicts a group of men, congregating in one of the newly-opened areas of Fukushima. Equipped with cameras and monitoring equipment, they seem to be examining the decontaminated earth; wondering, perhaps, just how polluted it really is.

Price’s engagement with broader themes of pollution and public health invites us to consider the parallels between the Fukushima Daiichi disaster and other public health issues, including COVID-19. “Picturing the Invisible” is an exhibition about Fukushima for COVID times. Its organization began in 2020. It was first hosted by the Royal Geographical Society in winter 2020, amid the Dela variant’s rise, and then at TU Munich in summer 2022, when the Omicron variant was ascendent. The shows were conducted under conditions of social distancing, mask mandates, and “track and trace” at a time when the pandemic was eclipsing the memory of the Fukushima Daiichi disaster. Visitors’ experience of the exhibition has undoubtedly been shaped by this context.

Many in Fukushima had hoped that the 10-year anniversary and the Tokyo 2020 Olympics—branded the “Recovery Olympics” by the Japanese government—would bring global attention to the challenges they continue to face. Though these hopes were to be frustrated by COVID-19, Price’s work suggests that—far from distracting us from the realities of life in Fukushima—our own experiences of COVID-19 might provide us with a lens through which to understand them. In Spring 2020, he used the same thermal imaging techniques he had deployed in Namie and Iitate to photograph the abandoned streets of London. Here too, an invisible danger was transforming out relationship to our surroundings. And, as in Fukushima, prosaic choices became suddenly pained. In the confusion of the first wave, decisions about when to leave the house, what to eat, and whether our children should play outside became negotiations of an unfamiliar risk. Price’s work makes visible the psychological burden of seeing an invisible danger all around you, common to the experience of both COVID-19 and the Fukushima disaster.

Lieko Shiga, “Portrait of Cultivation,” from the Rasen Kaigan (Spiral Shore) series (2010)

Few images are as arresting, or as difficult to parse, as Shiga’s Portrait of Cultivation. The couple stand in the night, like solitary specters, bathed in an arterial glow. Yet their body language is relaxed, tender even, and their countenances bemused. Then there is the root-like structure that protrudes from the man’s chest, impossibly large. Is it piercing him? Or sprouting from him—a physical manifestation of the specter’s rootedness? If home is where the heart is, then this couple seem tied to the soil on which they stand, the tendrils of the vegetative growth reaching for fertile ground.

“The land of Kitakama wasn’t always residential; and it used to be covered with big pine forests,” Shiga explains. “But people cultivated the land. They used their bare hands to dig up pine trees and build homes and farmlands.” One of the village elders tried to impress upon Shiga how backbreaking this labor was. Yet no explanation can substitute for experience, so Shiga took it upon herself to help dig out the roots of a small pine tree. The thick, gnarly roots belied the tree’s slender trunk, and through this physical exertion, Shiga felt able to commune with the generations who had once tilled this land. “The father of the elder … had been the leader of the cultivation. I felt like I met his father’s bones.” Excited, Shiga asked the elder to pose with the pine roots for this photograph.

Shiga’s Portrait of Cultivation has only grown more complex in the years since it was produced. Like her image of spirals etched into the shore, this photograph was taken before the triple disaster, but was published afterwards, and imbued with new resonances. Situated outside the exclusion zone, Kitakama was not affected by Japan’s evacuation orders. Nonetheless, the knowledge that so many have been forced from their land lends the photograph new poignancy. And if this couple’s (literal) rootedness helps us to understand why some have been so eager to return to Fukushima—some farmers going as far as to defy government orders to abandon their livestock, making six hour round trips into the exclusion zone to feed them every other day—then Shiga’s visual metaphor of a bodily growth also takes on new, more carcinogenic connotations in the wake of a nuclear disaster. As onlookers, we cannot know if the ghostly couple are among the dead. Yet we know that the land they worked has been transformed beyond recognition. The pine forest that once stretched along the coast, from Shiga’s studio to the Fukushima Daiichi power plant 80 kilometers away, has been scoured by the tidal waters.

Editors note: “Picturing the Invisible” has been exhibited at the Royal Geographical Society, London (October-December 2021), Technical University Munich (June 2022), and is now on view at the Heong Gallery, Downing College, Cambridge until April 23, 2023. All of the artworks, along with paired essays by experts, policymakers, authors, and activists, are available at the exhibit website.