The real horrors of ‘The Last of Us’ may already be here

By Erik English

MARCH 16, 2023

EDITOR'S NOTE: This article contains spoilers for The Last of Us, Season 1, and The Last of Us Part I video game.

Twenty-five minutes into the first episode of The Last of Us, Joel, his daughter Sarah, and his brother Tommy are fleeing their home as the world collapses. On the side of the road, a family is calling for help but they don’t stop. “They’ve got a kid,” says Tommy. “So do we,” Joel replies as they speed on and Sarah sits shocked and helpless in the back seat.

On the side of the road, a house is engulfed in flames, military caravans have blocked the roads, citizens are attacked in the streets, and a plane plummets from the air and explodes as their car flips. To escape the danger, Joel and Sarah flee away from the city and into the fields, chased by attackers. When all hope seems lost, a lone shot rings out and saves them from their would-be attacker.

Looking to see where the shot came from, a single soldier tells them not to move. Sarah’s arm is bleeding. “We’re not sick,” yells Joel. The soldier calls in to his superior. “Yes sir,” he says into his radio as he turns back to them, raises his gun, and fires. In a flurry of action, Joel spins to shield Sarah, but she’s hit. A moment later, his brother Tommy shoots the soldier but it’s too late. Sarah is dead.

This is the opening sequence of The Last of Us, HBO’s latest prestige drama about a post-apocalyptic, zombie-infested America. It’s noteworthy that within the first half of the episode, the main character encounters someone who is faced with a moral choice. He had just saved a father and his daughter from a zombie; the daughter is visibly injured but it’s unclear what the source was. Should he let them pass and hope they’re not infected? Will that risk the safety of non-infected populations if they are, indeed, infected? Ultimately, he is ordered to shoot them in the hopes of serving the greater good.

These questions will reverberate throughout the show and are typical of the storytelling style of The Last of Us. On its face, it's a fairly boilerplate zombie apocalypse show, focused on survival. But looking a little deeper, it’s clear the show has a great deal to say about our modern political moment. Dystopian and post-apocalyptic stories tend to reflect the social fears and anxieties of their time and can be useful metaphors for broader understanding. After three years of the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s no surprise that a post-apocalypse zombie story has had such a strong reception. As Daniel Drezner, the preeminent zombie scholar, explains, “Popular culture often provides a window into the subliminal or unstated fears of citizens, and zombies are no exception.”

The show, based on the beloved video game from 2013, is split into two levels. In the foreground, it is a fairly conservative story of survivalism and kinship. In the background, it is telling a different story about the failure of institutions during crises, the breaking of the social contract amid a turn towards authoritarianism, and the tradeoffs between utilitarianism and individual justice.

Embracing authoritarianism

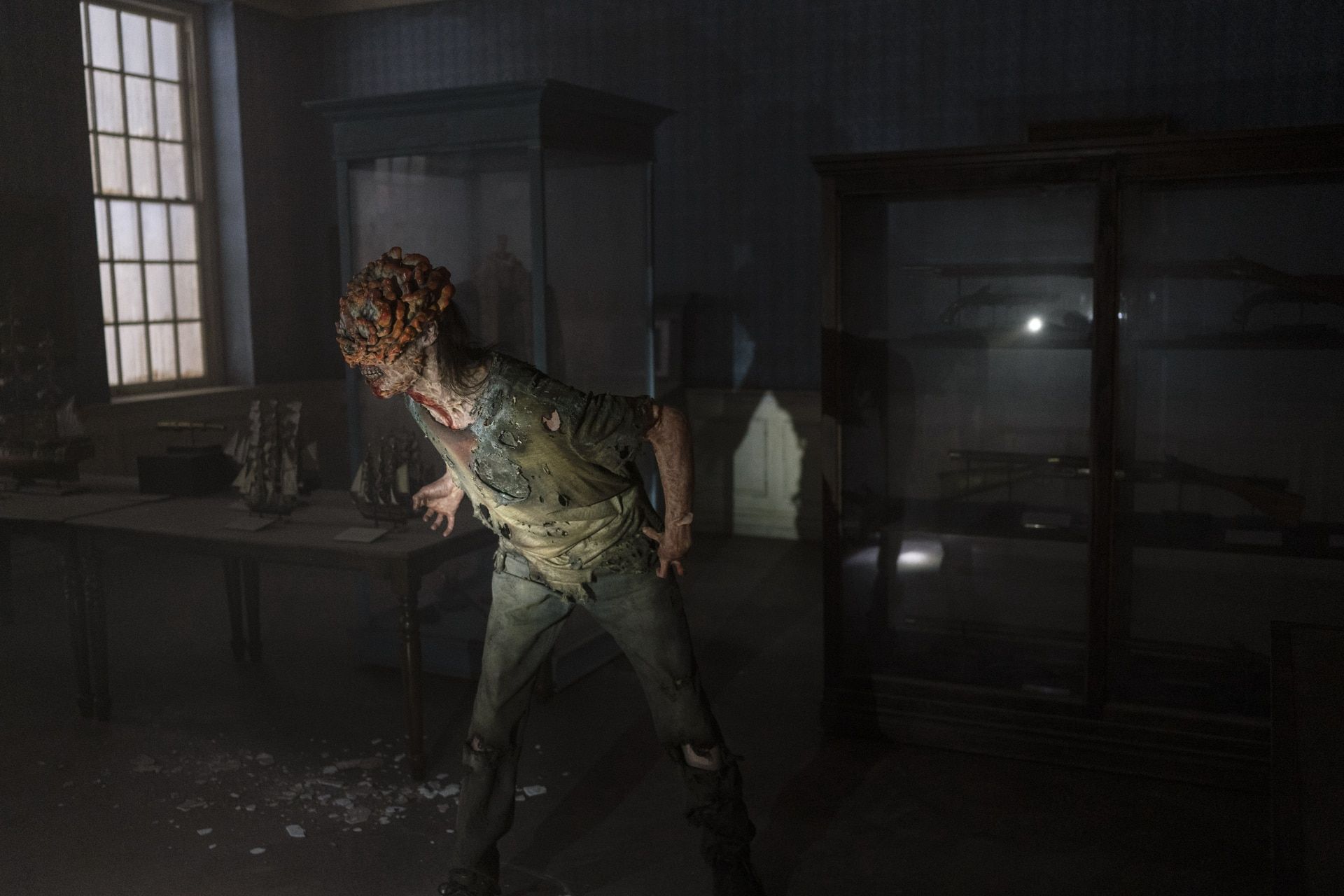

First thing’s first. Technically, the monsters in the show aren’t zombies. In the world of The Last of Us, the cordyceps fungus—a real fungus that attacks the brains of ants—has adapted to humans, thanks to global average temperatures rising from climate change. Spreading through global trade networks of bread, cereal, and pancake mix, the fungal infection creates a pandemic, taking mere days to turn most of humanity into hordes of zombie-ish monsters, called “infected.”

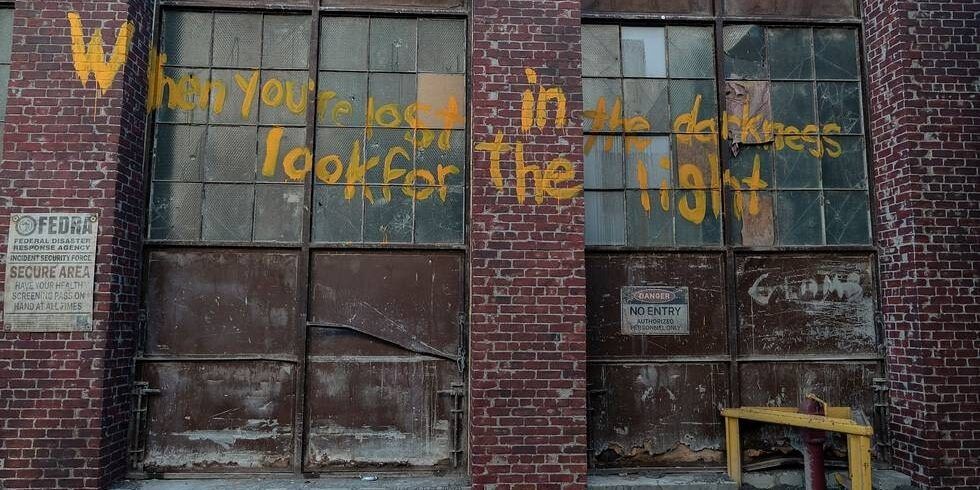

The main events of The Last of Us take place 20 years after the events in the opening sequence, after the world has collapsed. In place of the previous centralized government and globalized institutions, a totalitarian government agency has taken over the United States—the Federal Disaster Response Agency (FEDRA). In the original video game, FEDRA took control of the military and declared martial law, which never ended. In the show, the agency has merged with the military and controls decentralized quarantine zones without a centralized authority or guidance, regularly fighting insurrectionists and executing lawbreakers to solidify power and reduce dissent.

Totalitarian government is not a new feature of the post-apocalyptic zombie genre. As Joanna Weiss wrote in Politico in early February, “the public sector is not usually strong in zombie fiction.” But this also mirrors the rise of authoritarian regimes in the real world. Authoritarian gains have been outpacing democratic gains for the last 16 years. In 2021, 8 out of 10 people globally lived in a country that was judged to be only partly free or not free.

In The Last of Us, after the fall of an ineffective government, it makes sense that survivors would put their faith in the hands of those brutal enough to protect them from the new threats that exist. Joel (Pedro Pascal), now a broken shell of his former self, meets Ellie (Bella Ramsey) in FEDRA’s Boston quarantine zone (QZ). Ellie is a 14-year-old girl who has been infected but hasn’t “turned.” The Fireflies, a militia group that is fighting against FEDRA to restore democratic government, capture Ellie at the behest of Marlene, the head of their Boston operations. In the hopes of studying her to develop a vaccine, Marlene decides to transport Ellie to a Firefly research lab. After Marlene and the Fireflies are attacked, Joel is entrusted with transporting Ellie, a journey that will take them across the United States, where they dodge FEDRA, raiders, and worse.

Disease X

The show has grown increasingly popular with each episode of its first season, with more than eight million people viewing its eighth and ninth episodes. In particular, the fungus that sets off the zombie-ish pandemic has tapped into a real-life social nerve. Mycologists have been swarmed with questions about how likely the probability of a cordyceps fungus adapting to humans might be. The answer is: not very high, but not zero, either.

The World Health Organization (WHO) regularly publishes a list of pathogens with epidemic potential. Among the current priority diseases are COVID-19, Ebola, Marburg, and "Disease X”, referring to the knowledge that an epidemic or pandemic could be caused by something that is currently unknown. Until recently, there had been very little research into the pandemic potential of fungi. But at the end of 2022, the WHO released a list of fungal priority pathogens, the first serious effort to prioritize fungal pathogens. Cordyceps didn’t make the list.

In the original game version of the story, the fungus is spread by spores and bites (naturally), so players wear masks in certain areas. In the show, the spores are done away with for storytelling purposes and the fungus is presented as a large, interconnected organism, which mostly spreads by bites (or a kiss of death) from an infected.

Fungal pathogens are dangerous and worth researching because they can release spores and have been shown to be adaptable to changing environments. It’s also worth noting that the largest known organism is a fungus in eastern Oregon that spans four square miles. While it’s unlikely fungi will cause a zombie apocalypse, certain kinds of fungus do regularly infect the respiratory systems of the immune-compromised: the elderly, the young, and those with immune-deficiency illnesses. During the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a higher occurrence of comorbidity with fungal infections because of how COVID attacks the respiratory system.

Caught off-guard

In the show, there is no cure for the spreading fungus, and society collapses within a few days. When asked what can be done to stop the infection, an Indonesian professor of mycology replies in episode 2: “Bomb the city and everyone in it.” There are scenes later on showing the craters of those dropped bombs. Existing institutional capacity is no match for the contagiousness of the cordyceps fungus.

As part of their evaluation of priority fungal pathogens, the WHO recommends three priorities to prevent pandemics: strengthening laboratory capacity and surveillance; sustainable investments in research, development, and innovation; and public health interventions. The only problem is, even if we know what to do, we don’t necessarily do it. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the significant pushback that emergency health initiatives can receive.

As in the show, world governments were caught off guard by the emergence of COVID-19. News reports at the time were filled with ventilator shortages, a lack of personal protective equipment for health workers, and pushback against masks and vaccination mandates. A 2022 PEW research poll found that 46 percent of Americans felt that public health officials were unprepared for the COVID-19 outbreak.

During the Trump administration, Operation Warp Speed helped to deliver lifesaving COVID-19 vaccines in record time, saving millions of lives around the world. However, despite the success of the program, those who served in the administration have been reluctant to take credit, with some exploiting vaccine hesitancy for political gain.

At one point, the Trump administration even threatened to pull out of the WHO over the “failed response” to the pandemic. The rhetoric around the initial failed response has further hollowed trust in public health institutions. According to a February 2022 poll from PEW Research, only 29 percent of US adults say they have “a great deal of confidence” in medical scientists to act in the public’s interest. That’s down from roughly 43 percent in April 2020. In parallel, some mainstream politicians have been dismissive of COVID precautions as theater, criticizing government interventions and casting blame when infections increase.

This doesn’t bode well for prospects of avoiding future pandemics. A particular irony of public health interventions is that when they’re successful, they tend to look like an overreaction, because the intervention averted the public health crisis. We shouldn’t need to experience an apocalypse to decide we actually want to avoid one.

Broken social contract

Outside of the relative safety of the Boston QZ, Joel and Ellie are confronted with the harsh reality of the world that remains. They are immediately confronted with the most pronounced landmark of the show, the Massachusetts State House, its golden dome overgrown with vines, in a nod to the irrelevance of the previous social order.

In episode 3, Nick Offerman plays Bill, a doomsday prepper who gets his wish when the world ends. It’s only years later, after he meets and falls in love with Frank (Murray Bartlett), that he realizes there is something worth saving in the world. The stark political contrast between him and Frank is exemplified in an exchange between the two during a fight:

“You live in a psycho bunker where 9/11 was an inside job and the government are all nazis,” says Frank.

“The government are all nazis!” shouts Bill.

“Well, yeah, now. But not then!”

This attempt to dismiss the doomsday prepper mentality is funny but falls a little flat when Bill is shown as being so prepared and competent as a survivor. Some have thrown this out as an example of the show’s inherently conservative bent, musing that conservative critics of the show would actually like it, if they could stop tripping over themselves over the portrayal of a meaningful gay relationship. Ultimately, even though his survivalist skills are what protect them, characters still percieve Bill’s isolationist and survivalist tendencies as being over the top. In the game, Frank gets tired of Bill’s survivalist rules and abandons him, accidentally getting infected and hanging himself. In the show, Bill is a competent survivalist committed to an isolationist lifestyle, but the main takeaway is that his relationship with Frank teaches him that it’s possible to live a happy life in a terrifying world.

This is extended further as the show takes time to demonstrate that even those who overthrow a tyrannical government do not necessarily make good leaders who care about those they lead. In episode 5, a militia overthrows FEDRA in Kansas City, known to be particularly brutal to the local population. The militia leader, Kathleen, has earned the respect of militia members through her ruthlessness. Instead of implementing improved governance for Kansas City, she doubles down. Rather than addressing the literal monster under the city, Kathleen chooses to consolidate power by chasing down dissenters. As a result, she and her henchman die brutally at the hands of the infected, the enemy from whom she was supposed to be protecting her community.

For a zombie show, there aren’t a lot of zombies-ish monsters in The Last of Us. Instead, everyone is primarily concerned with helping themselves, and selfishness becomes the motivating factor of the villains, with the zombies lurking offscreen much of the time. In the show, as in the game, human nature is reduced to its most primal urge: self-preservation. To care about anyone is to risk your life. “Be careful who you put your faith in. The only people who can betray us, are the ones we trust,” Ellie is warned in episode 6.

Post-apocalyptic morality

In the final episode, Joel and Ellie reach Salt Lake City, where the Fireflies will ostensibly be able to develop a vaccine, and both are promptly knocked out by a Firefly stun grenade. Joel wakes up in a hospital room where Marlene explains that Ellie is being prepared for surgery. In order to develop a vaccine, the part of Ellie’s brain that has been exposed to the cordyceps fungus has to be removed. Developing a vaccine will kill her, but Marlene kept that information from her.

As the main events of the story begin, Joel has learned to survive in the world of cordyceps and accepts it. He is violent and cynical and does not believe that happiness is achievable anymore. His journey with Ellie has changed him, and he’s finally able to care for another person again. Learning that creating the vaccine will kill Ellie is the culmination of that emotional journey and he resolves to save her, destroying the Fireflies in the process.

After escaping the operating room with Ellie, Joel encounters Marlene, who begs him to think of the greater good. To this point, the objective of the story has been to get Ellie to the Fireflies, develop a vaccine, and save humanity. Holding Ellie, Joel is returned to the opening sequence of the show and faces the same decision that the soldier who killed Sarah faced. Only now, to save humanity, Ellie must die, a utilitarian sacrifice for the greater good. Instead, Joel kills Marlene, effectively dooming humanity. The show’s ending will undoubtedly be controversial, as the game's ending was.

Lessons of apocalyptic fiction

There is a legitimate concern that shows like The Last of Us and other doomsday narratives fetishize apocalypse, glorify violence, and lionize survivors for having what it takes. In fact, studies have shown that watching post-apocalyptic or doomsday stories can actually lead to an increased proclivity for violence in emergencies. But there are still valuable lessons to take from apocalyptic fiction.

There are some dystopian and post-apocalypse writers who use the genre to highlight emergency and disaster preparedness. Max Brooks’ novel World War Z (just ignore the movie) is a classic of the zombie genre and uses zombies as a metaphor for SARS. The story views the pandemic through a geopolitical lens to, as one reviewer put it, criticize “government ineptitude, corporate corruption and general human short-sightedness.” The conflict is ultimately resolved when US policy shifts and is dramatically restructured to restart the economy, reevaluate certain kinds of labor, and focus on eradication of the zombie virus.

Practically, if Joel had chosen to sacrifice Ellie and the Fireflies had been able to produce a vaccine, the political realities would still prevent any kind of post-apocalyptic societal renaissance. The plights facing the world are bigger than the cordyceps virus and the institutional capacity to implement an effective public health measure no longer exists. Morally, even if the cordyceps pandemic, democratic decline into authoritarian rule, and broken social contract could all be fixed by a vaccine, a world that sacrifices a child to save itself isn’t worth saving.

As has been previously written in the Bulletin, sometimes the best way to prepare for a pandemic or an emergency is to find a useful vessel for that information. Not many people will read epidemiological reports in scientific journals, so in 2011 the CDC took advantage of the popular zombie obsession and created a zombie preparedness website. The director, Ali Khan quipped, “if you are generally well equipped to deal with a zombie apocalypse, you will be prepared for a hurricane, pandemic, earthquake, or terrorist attack.” When it first launched, the website was so popular that it crashed.

The COVID-19 pandemic proved that the world was not ready for a fast-traveling, highly contagious virus. Moreover, that lack of preparedness exacerbated the lack of trust in institutions to implement safety precautions in a timely manner and, at times, the lack of trust we hold in each other. Those failings have been exploited politically to undermine experts, increasing the likelihood that future health guidance will be ignored.

Dystopian and post-apocalyptic stories can be helpful tools for conceptualizing challenges that face society. The Last of Us is at base a cautionary tale, warning that the specific dangers of public health crises aren’t confined to disease—they include the risk that complacency and fear will snowball into a true dystopia. Before the next pandemic strikes, we should imagine an ending that represents the values we hold and aspire to, rather than the fears we resort to in despair, because life is about more than just surviving.

This is an article that everyone (of all political ‘stripes’) should read. The failure of our response to COVID-19 was not just a failure of Public Health (or whoever you blame) but a failure of Society and a significant number of everyday normal citizens. It exposed our base ignorance and distrust and our base urges and humanity. I especially appreciated the observation that ‘successful’ Public Health initiatives always ‘look like an overreaction’, precisely because the worst outcomes don’t appear. Good writing. Good analyses. (And ‘good luck’ having this message sink-in in all quarters of our society / societies. Here, I… Read more »