Double Flash: Forty years ago, the Carter administration covered up a presumed Israeli nuclear test

By John Krzyzaniak | September 25, 2019

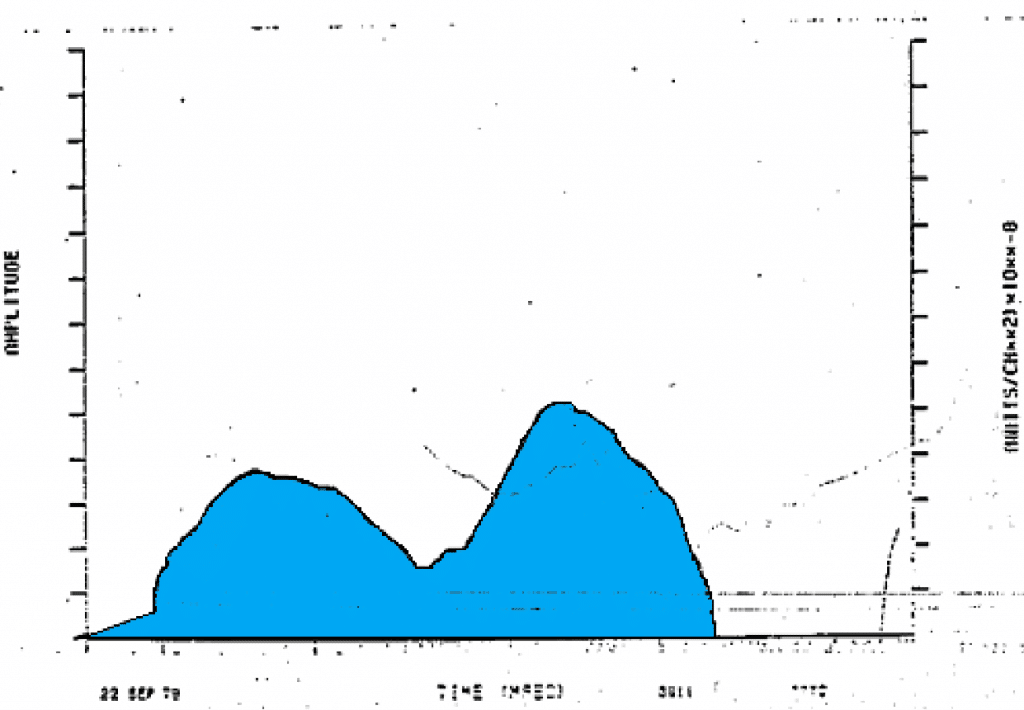

The optical signal recorded by one of the Vela satellite’s sensors on September 22, 1979. Credit: 1980 Ruina Report, shaded for clarity.

The optical signal recorded by one of the Vela satellite’s sensors on September 22, 1979. Credit: 1980 Ruina Report, shaded for clarity.

On September 22, 1979, a US Vela satellite detected a “double flash” signal far off the coast of South Africa. It was the tell-tale sign of an atmospheric nuclear explosion: US Vela satellites, launched to help enforce the Partial Test Ban Treaty, had detected 41 previous double flashes, and all of them were caused by known nuclear tests. That night, President Jimmy Carter wrote in his diary: “There was indication of a nuclear explosion in the region of South Africa—either South Africa, Israel using a ship at sea, or nothing.” His administration would eventually decide, contrary to the evidence, to push the theory that it was the last of these three possibilities that had occurred.

While publicly available information cannot definitively prove that Israel conducted an illegal nuclear test that night, Foreign Policy has published a collection on the 40th anniversary of the event that shows how evidence in support of that theory is mounting, and why the mysterious flash still matters.

At the time, within the White House, there was apparently little doubt about what had happened. Several months after the event, on February 27, 1980, Carter wrote in his diary, “we have a growing belief among our scientists that the Israelis did indeed conduct a nuclear test explosion in the ocean near the southern end of Africa.”

Still, the administration put together a panel, led by Jack Ruina, to determine the cause of the double flash signal. In May 1980, the panel laid out an alternative theory in its report: that a tiny meteor had hit the satellite and broken into smaller particles that then perfectly reflected the sunlight in such a way as to mimic the signal from a nuclear explosion. Even though the panel hedged on the likelihood that its explanation was the correct one, it nevertheless concluded that, in any event, the signal was “probably not” from a nuclear explosion.

In recent years, more data about the event has become available in declassified documents, as Bulletin contributors have previously noted. Drawing on some of this data, Lars-Erik De Geer and Christopher Wright co-authored two scientific papers in which they conducted independent analyses of the raw data. In the first, they obliterate the meteoroid theory. In the second, they examine iodine 131 found in the thyroid glands of Australian sheep that were slaughtered in October and November 1979 and conclude that the data was consistent with a nuclear detonation on September 22.

Once one is convinced that there was in fact a nuclear explosion, it’s only a short step to figuring out who did it. None of the five recognized nuclear weapons states at the time would have had any need to perform a small clandestine test at sea. Pakistan, India, and South Africa could be ruled out too, since such a test would not have been feasible for them given the nuclear development and logistical difficulties it entailed. That left Israel, which had both the motivation and capability, as the sole candidate.

The consequences of acknowledging that Israel had conducted a nuclear test would have been grave, and that’s why the Foreign Policy contributors believe the Carter administration refused to admit it. Such a test would have been a violation of the Partial Test Ban Treaty, which Israel had ratified in 1964. More important, US laws would have required the triggering of sanctions against Israel, which for political reasons Carter was keen to avoid.

Though keeping the matter a secret may have been politically expedient at the time, the opposite may be true now. As Henry Sokolski writes in his contribution, the prospect of the US government sharing what it knows about the incident now “would seem to make sense, as it would help discourage future violations of pledges not to test by countries such as Iran, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Turkey, South Korea, Japan, and other aspirational nuclear states.” Or, put differently, to acknowledge the test would be to uphold an important nonproliferation norm, whereas continued silence leaves the United States open to the charge of hypocrisy.

Publication Name: Foreign Policy

To read what we're reading, click here

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Israel, Partial Test Ban Treaty, iodine-131, nuclear testing

Topics: Nuclear Weapons, What We’re Reading