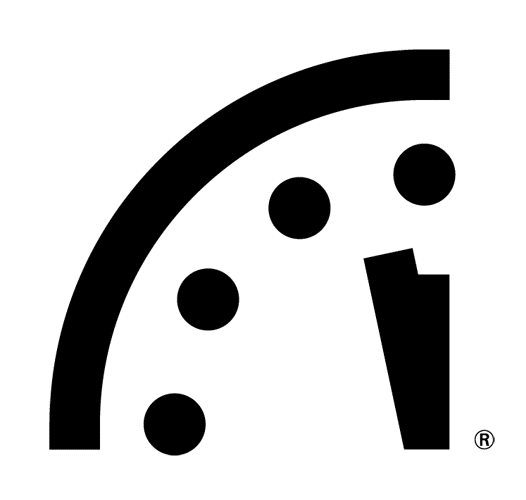

At doom’s doorstep:

It is 100 seconds to midnight

At doom’s doorstep: It is 100 seconds to midnight

2022 Doomsday Clock Statement

Science and Security Board

Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

Editor, John Mecklin

2022 Doomsday Clock Statement

Science and Security Board

Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

Editor, John Mecklin

It is 100 seconds to midnight

Editor’s note: Founded in 1945 by Albert Einstein and University of Chicago scientists who helped develop the first atomic weapons in the Manhattan Project, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists created the Doomsday Clock two years later, using the imagery of apocalypse (midnight) and the contemporary idiom of nuclear explosion (countdown to zero) to convey threats to humanity and the planet. The Doomsday Clock is set every year by the Bulletin’s Science and Security Board in consultation with its Board of Sponsors, which includes 11 Nobel laureates. The Clock has become a universally recognized indicator of the world’s vulnerability to catastrophe from nuclear weapons, climate change, and disruptive technologies in other domains. In March 2022, the Science and Security Board released a new statement in the wake of Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Read it here.

To: Leaders and citizens of the world

Re: At doom’s doorstep: It is 100 seconds to midnight

Date: January 20, 2022

Last year’s leadership change in the United States provided hope that what seemed like a global race toward catastrophe might be halted and—with renewed US engagement—even reversed. Indeed, in 2021 the new American administration changed US policies in some ways that made the world safer: agreeing to an extension of the New START arms control agreement and beginning strategic stability talks with Russia; announcing that the United States would seek to return to the Iran nuclear deal; and rejoining the Paris climate accord. Perhaps even more heartening was the return of science and evidence to US policy making in general, especially regarding the COVID-19 pandemic. A more moderate and predictable approach to leadership and the control of one of the two largest nuclear arsenals of the world marked a welcome change from the previous four years.

Still, the change in US leadership alone was not enough to reverse negative international security trends that had been long in developing and continued across the threat horizon in 2021.

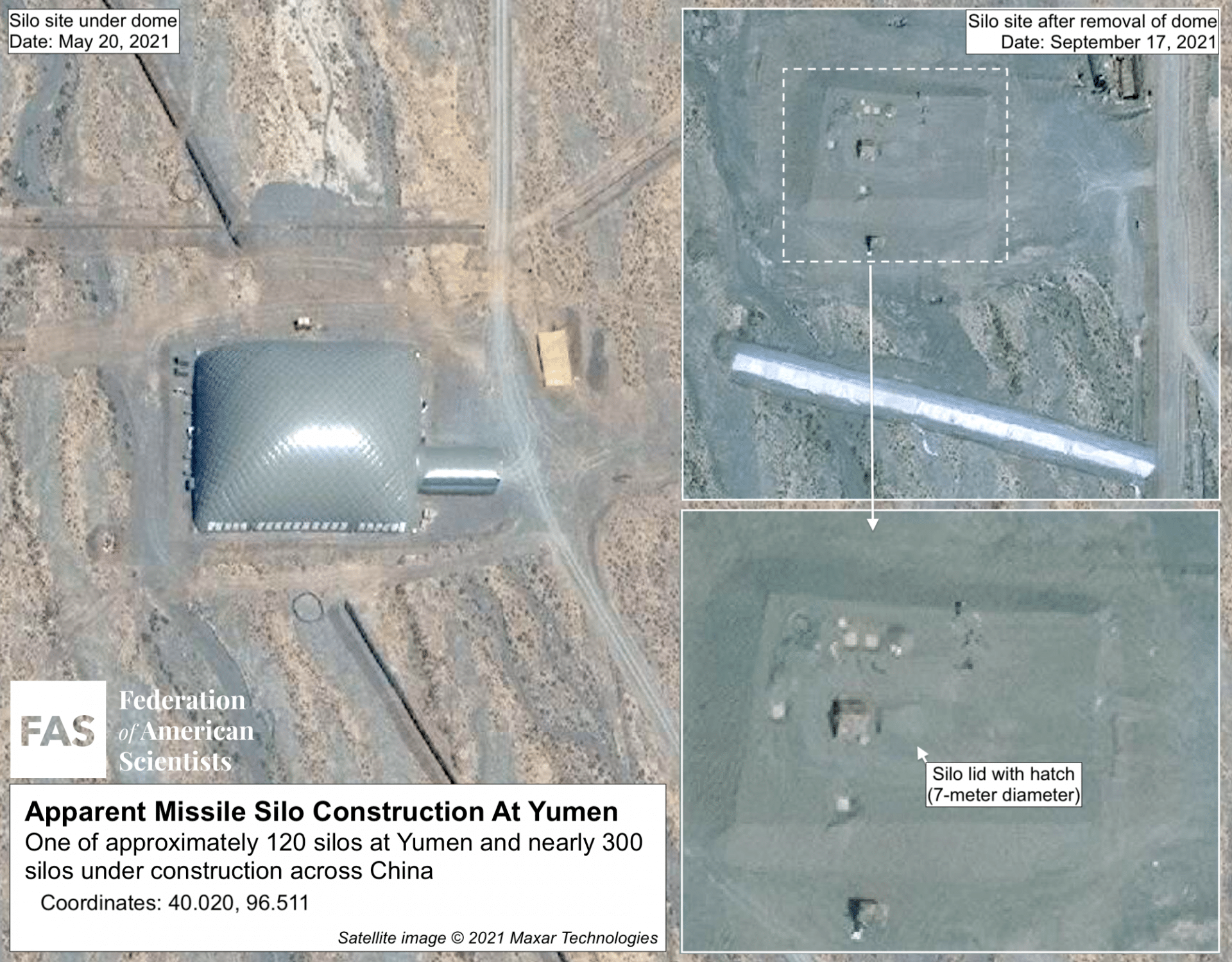

US relations with Russia and China remain tense, with all three countries engaged in an array of nuclear modernization and expansion efforts—including China’s apparent large-scale program to increase its deployment of silo-based long-range nuclear missiles; the push by Russia, China, and the United States to develop hypersonic missiles; and the continued testing of anti-satellite weapons by many nations. If not restrained, these efforts could mark the start of a dangerous new nuclear arms race. Other nuclear concerns, including North Korea’s unconstrained nuclear and missile expansion and the (as yet) unsuccessful attempts to revive the Iran nuclear deal contribute to growing dangers. Ukraine remains a potential flashpoint, and Russian troop deployments to the Ukrainian border heighten day-to-day tensions.

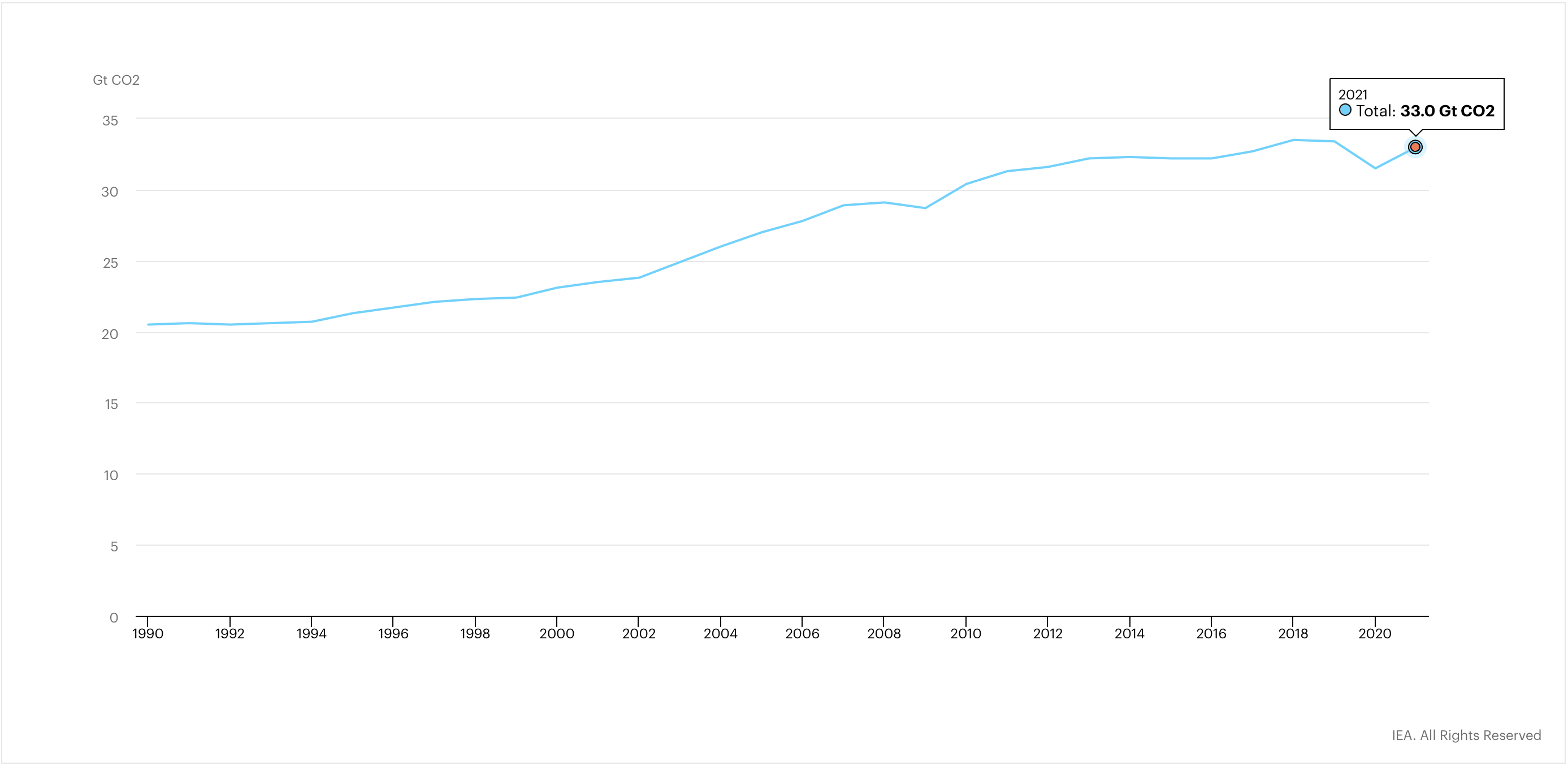

For many countries, a huge gap still exists between long-term greenhouse gas-reduction pledges and the near- and medium-term emission-reduction actions needed to achieve those goals. Although the new US administration’s quick return to the Paris Agreement speaks the right words, it has yet to be matched with actionable policies.

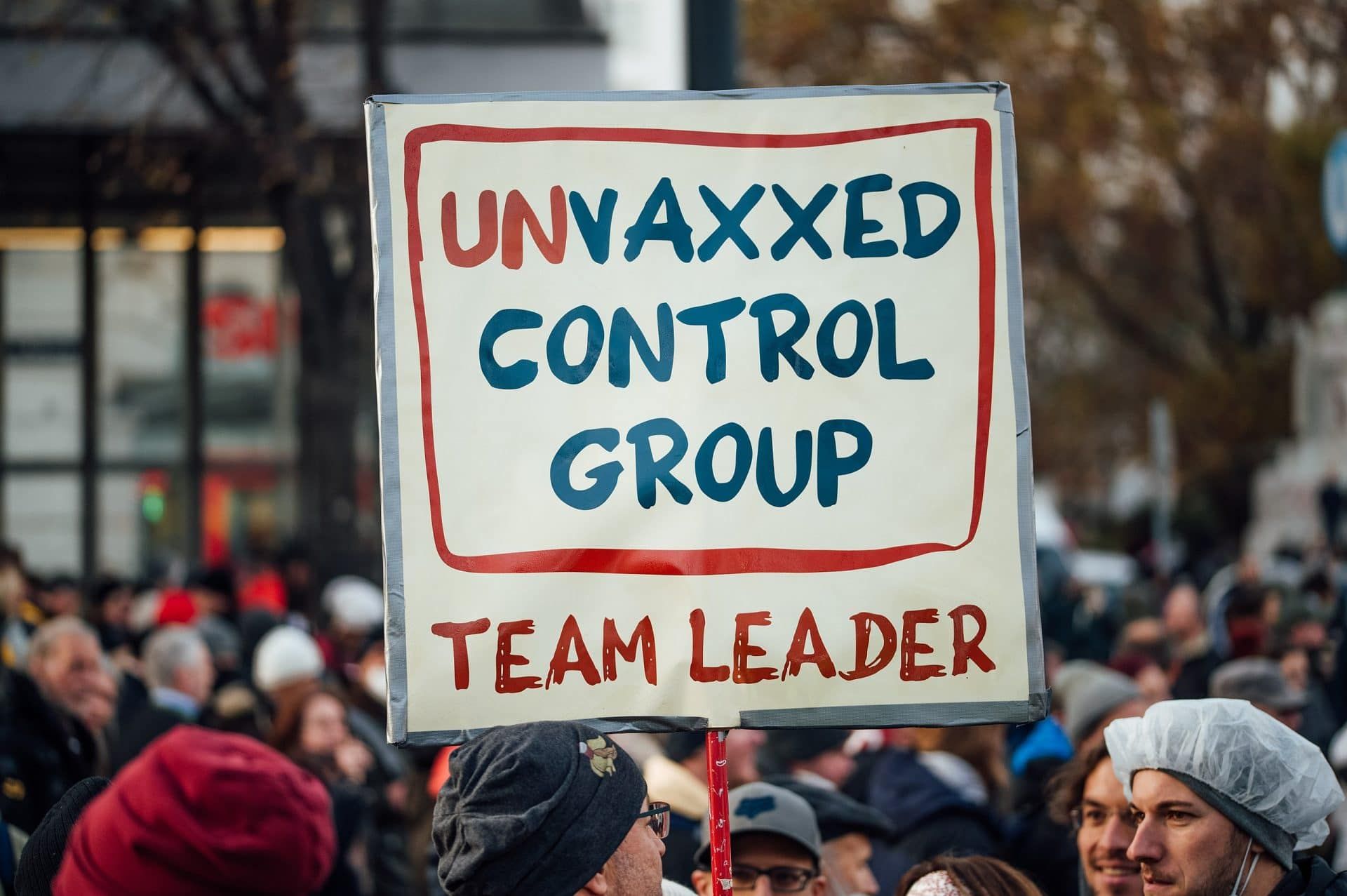

Developed countries improved their responses to the continuing COVID-19 pandemic in 2021, but the worldwide response remained entirely insufficient. Plans for quick global distribution of vaccines essentially collapsed, leaving poorer countries largely unvaccinated and allowing new variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus to gain an unwelcome foothold. Beyond the pandemic, worrying biosafety and biosecurity lapses made it clear that the international community needs to focus serious attention on management of the global biological research enterprise. Further, the establishment and pursuit of biological weapons programs marked the beginning of a new biological arms race.

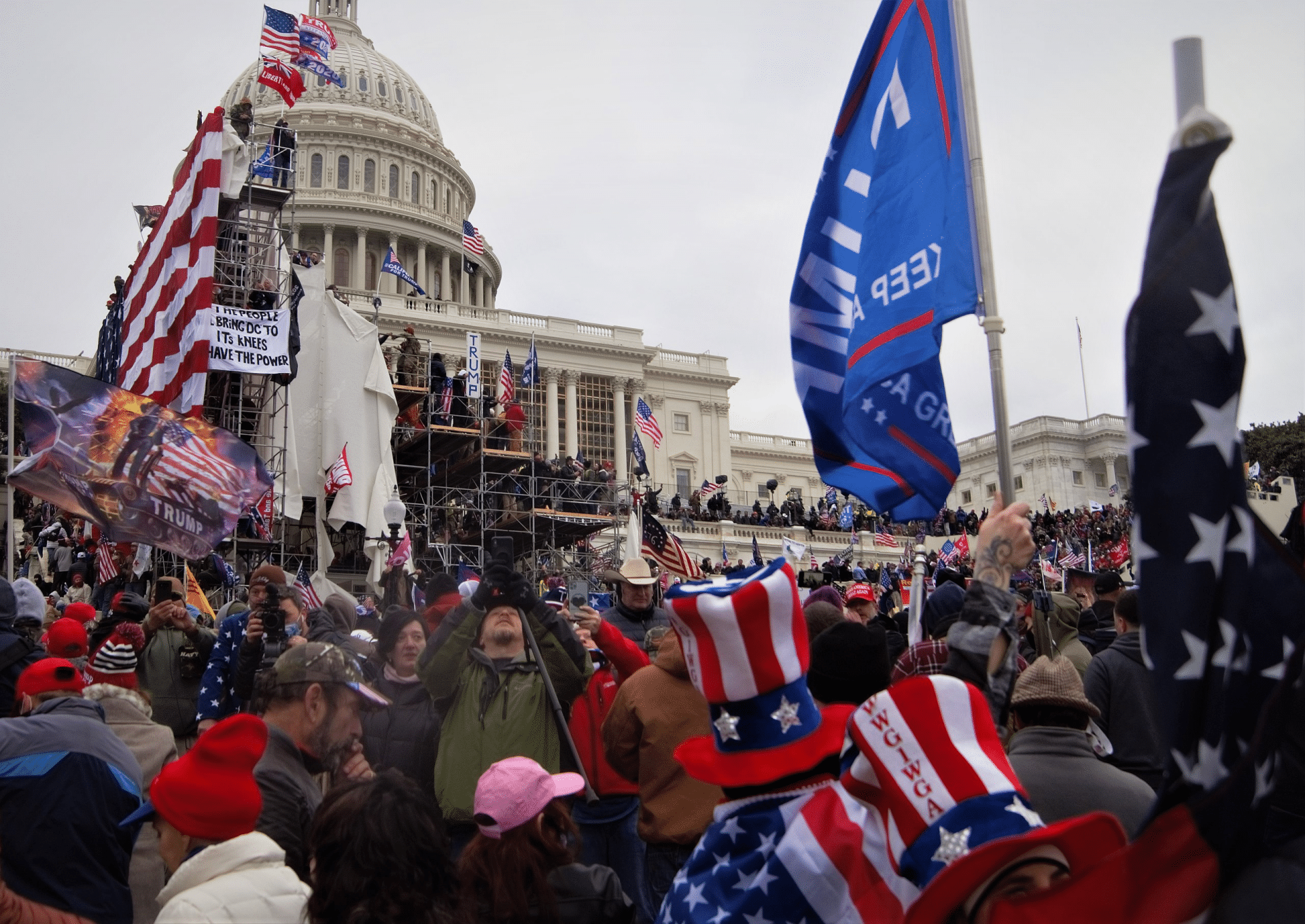

And while the new US administration made progress in reestablishing the role of science and evidence in public policy, corruption of the information ecosystem continued apace in 2021. One particularly concerning variety of internet-based disinformation infected America last year: Waves of internet-enabled lies persuaded a significant portion of the US public to believe the utterly false narrative contending that Joe Biden did not win the US presidential election in 2020. Continued efforts to foster this narrative threaten to undermine future US elections, American democracy in general, and, therefore, the United States’ ability to lead global efforts to manage existential risk.

In view of this mixed threat environment—with some positive developments counteracted by worrisome and accelerating negative trends—the members of the Science and Security Board find the world to be no safer than it was last year at this time and therefore decide to set the Doomsday Clock once again at 100 seconds to midnight. This decision does not, by any means, suggest that the international security situation has stabilized. On the contrary, the Clock remains the closest it has ever been to civilization-ending apocalypse because the world remains stuck in an extremely dangerous moment. In 2019 we called it the new abnormal, and it has unfortunately persisted.

Last year, despite laudable efforts by some leaders and the public, negative trends in nuclear and biological weapons, climate change, and a variety of disruptive technologies—all exacerbated by a corrupted information ecosphere that undermines rational decision making—kept the world within a stone’s throw of apocalypse. Global leaders and the public are not moving with anywhere near the speed or unity needed to prevent disaster.

Leaders around the world must immediately commit themselves to renewed cooperation in the many ways and venues available for reducing existential risk. Citizens of the world can and should organize to demand that their leaders do so—and quickly. The doorstep of doom is no place to loiter.

The nuclear tightrope

During 2021, some nuclear risks declined while others rose. Upcoming decisions on nuclear policies could generate either salutary or dangerous modifications of an already uncertain and worrisome security situation.

The February 2021 agreement between the United States and Russia to renew New START for five years is a decidedly positive development. This extension creates a window of opportunity to negotiate a future arms control agreement between the two countries that possess 90 percent of the nuclear weapons on the planet. The United States and Russia also agreed to start two sets of dialogues about how to best maintain “nuclear stability” in the future: the Working Group on Principles and Objectives for Future Arms Control and the Working Group on Capabilities and Actions with Strategic Effects. These groups have met and in early 2022 are expected to report on initial results of the consultations, aimed at shaping future arms control agreements.

Another bright spot was the Biden administration's announcements that it would seek to return to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) with Iran and offer to enter strategic stability talks with China. Although no talks between North Korea and the United States took place in 2021, the North Koreans have not resumed testing of nuclear weapons or long-range intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). (Tests of shorter-range missiles have continued.) Finally, when the Biden administration began its Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) process, it announced that one specific goal would be to “reduce the role of nuclear weapons” in US national security policy.

Other developments, however, appeared on the negative side of the ledger:

Iran continues to build an enriched uranium stockpile, insisting that all sanctions be removed before returning to talks with the United States on the JCPOA. The window of opportunity seems to be closing. Over time, Iran's neighbors, particularly Saudi Arabia, may feel compelled to acquire similar capabilities, foreshadowing the frightening possibility of a Middle East with multiple countries with the expertise and material to build nuclear weapons.

The Chinese have started to build new ICBM silos on a large scale, leading to concerns that China may be considering a change in its nuclear doctrine. China and Russia have both tested anti-satellite weapons recently, increasing concerns about rapid escalation in any conventional conflict with the United States. Efforts by all three countries to field hypersonic missiles are beginning to yield results, intensifying competition. While experts disagree on both the causes and the consequences of these programs, they clearly mark the start of a new arms competition.

The North Koreans continue to test nuclear-capable short- and medium-range missiles, including cruise, ballistic, and glide vehicles, and there is evidence of their restarting plutonium production. Meanwhile, there have been no high-level negotiations between the United States and North Korea. India and Pakistan continue to advance their nuclear, missile, and other military capabilities with no diminution of possible flash points that could lead to nuclear conflict.

As the January 6, 2021 insurrection at the US Capitol demonstrated, no country is immune from threats to its democracy, and in a state with nuclear-weapons-usable material and nuclear weapons, both can be targets for terrorists and fanatics. Notably, the insurrectionists came close to capturing Vice President Mike Pence and the “nuclear football” that accompanies the vice president as the backup system for nuclear launch commands. More than 10 percent of those charged with crimes during the January 6th insurrection were veterans or active service members. The Pentagon has conducted a major review of extremism in the military and has adopted new definitions of extremist activities in an attempt to reduce this danger in the future. The seriousness of the problem is clear.

Finally, the United States is preparing a Nuclear Posture Review to guide US strategy, policy, and deployments of nuclear weapons, but its overall message appears not yet decided. We hope the document will assert that the United States will reduce the role of nuclear weapons in its deterrence and defense policies, which in turn may positively affect the nuclear weapons postures of other countries, leading, we believe, to a safer world. Where we set the Clock next year will be influenced by what the Nuclear Posture Review ultimately contains. Reports of congressional interference in the process, resulting in the firing of personnel conducting the review, suggests unwelcome politicization that could well affect the outcome and make more rational nuclear weapons policies hard to effect.

Climate change: Lots of words, relatively little action

This past year’s climate negotiations in Glasgow marked an important milestone in climate multilateralism: a critical first round of the treaty’s cycle of upgrading national efforts. Countries were under pressure to strengthen their emission-reduction pledges significantly relative to their pledges six years ago in Paris. The results, unfortunately, were insufficient. China and India affirmed that they would move away from use of coal, but only gradually; they affirmed for the first time the objective of achieving “net zero,” but only in 2060 and 2070, respectively. There was only partial progress toward defined accounting rules to allow international markets for greenhouse gas emissions and removals to develop. Developed countries again failed to follow through on treaty commitments to provide necessary financial and technological support. Overall, countries’ projections and plans for fossil fuel production are far from adequate to achieve the global Paris goals to limit the warming of the surface of the planet to “well below two degrees Celsius” (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) relative to the temperature around 1800, at the beginning of the industrial revolution.

Encouragingly, several countries (as well as financial institutions and corporations) have announced a commitment to achieve net-zero carbon dioxide emissions for the long term—meaning by 2050 or thereabouts. These announcements are significant, in that reaching zero aggregate carbon dioxide emissions globally would halt the buildup of greenhouse gas pollution in the atmosphere, which is absolutely critical to halting yet more warming. Earnest efforts to reach these seemingly distant targets require concerted actions in the immediate term, including a redirection of investment away from the production and use of fossil fuel and toward renewables and energy efficiency, massive upgrading of existing infrastructure, and a shift in land use and agriculture practices. The real test of the significance of these net-zero pledges will be whether they are matched by near- and medium-term emission-reduction actions.

Last year, we noted optimistically the election of a US president who “acknowledges climate change as a profound threat and supports international cooperation and science-based policy,” and we’ve seen a dramatic change in tone from the previous presidential administration. Recognizing that “[t]he effects we are seeing of climate change are the crisis of our generation,” Biden has indeed attempted to move forward quickly, reentering the United States in the Paris Agreement and announcing the United States’ updated Paris emission pledge of a 50 percent reduction by 2030. He has also signaled an attentiveness to the connection between climate action and environmental justice, in both the domestic and international contexts. He has committed to making climate investments in disadvantaged communities within the United States, and at the UN General Assembly meeting he pledged to double climate financing to developing countries.

However, progress achievable through the US political process is highly constrained and fragile, as any subsequent president may try to swing the pendulum backward. The major infrastructure package passed in 2021 is less of a “climate bill” than the Biden administration initially proposed, and the fate of the climate goals of the “Build Back Better” bill hangs in the balance of a starkly divided Congress. It thus is not yet clear how much progress the United States will make in the coming year toward its announced emissions reduction pledge and finance promise.

For over four decades the threat of climate change to “future generations” has been ruefully noted. As warming has continued to drive up temperatures—from an unprecedented extreme high temperature of 100 degrees Fahrenheit in the Siberian Arctic to the record-breaking 2021 “heat dome” over western Canada and the United States—today’s young people are increasingly seeing themselves as the future victims. They are witnessing human and ecosystem tragedies caused, for example, by droughts in eastern Africa and the United States, floods in China and Europe, and wildfires raging around the world, harbingers of yet more dire consequences as climate change accelerates in their lifetimes.

The experience of a deepening crisis has animated protests and other civil society expressions of alarm this year. These have occurred at major political events (such as the G7 Summit), by youth climate movements (such as the student-led Fridays for Future protests around the world), at September’s Climate Week in New York, at COP26 in Glasgow, and at individual sites of proposed new fossil fuel infrastructure (such as Line 3 in the United States, the Trans Mountain Pipeline in Canada, and the EACOP pipeline in Uganda and Tanzania). These actions focus public attention on climate change and raise its political salience, but whether they will transform policies, investments, and behaviors remains among the most important questions facing global society.

The burgeoning biological threat to civilization

For years, the United States and many other countries underinvested in defense against natural, accidental, and intentional biological threats. They also underestimated the impacts that a biological threat could have on the entire world. COVID-19 revealed vulnerabilities in every country and the world’s collective ability to prepare for, respond to, and recover from infectious disease outbreaks.

The COVID-19 pandemic rightly has absorbed the world’s attention, given its demonstrated ability to sicken and kill millions, weaken national economies and global supply chains, and destabilize governments and societies. And yet, what the world has experienced during this pandemic is nowhere close to a worst-case scenario.

To deal with the crisis at hand, the world is focusing almost all its efforts on COVID-19, to the exclusion of other biological threats. The scope of potential biological threats is expansive. Preventing and mitigating future biological events will require a wider lens for viewing biological threats. For example, slow vaccination rates have allowed virus mutations, perpetuating the threat from COVID-19. Similarly, failing to address antibiotic resistance could trigger a worldwide pandemic involving antimicrobial-resistant organisms within a decade. Research into novel diseases has proliferated high-containment laboratories around the world. Some of those labs inadvertently release pathogens into the environment. Some regimes to monitor and regulate these laboratories are perceived by their researchers to be excessively burdensome and restrictive. At the same time, the Biological Weapons and Toxin Convention still struggles to find effective ways to enforce its prohibitions on the development and production of biological agents and weapons.

This year, the US Department of State declared that Russia and North Korea possess active biological weapons programs and expressed concern about dual-use biological research programs in China and Iran. Terrorist organizations such as Al Qaeda and ISIS and some criminal organizations continue to profess their determination to build, acquire, and use biological weapons to achieve their goals. The globally inadequate response to COVID-19 only serves to underscore that an attack using a weapon containing biological agents designed to resist existing medical countermeasures could provide attackers with some of the tactical, operational, strategic, and economic advantages they seek. The US Department of Defense is now concerned enough about that prospect to undertake a biological posture review.

The world now lives in an age of biological innovation. Many countries and corporations are making enormous investments in biological science, biotechnology, and combinational science and technology (in which biology combines with other fields), recognizing that they have immense opportunities to establish and grow bio-economies. Innovative biological research and development efforts simultaneously increase and decrease biological risk. The field is moving quickly.

CRISPR-Cas9, the revolutionary genetic engineering tool that scientists in the United States and Sweden discovered in 2012, is cheap and ubiquitous today, spurring investments in genetic testing and adult stem cell technologies. Countries and non-state actors are exploring ways to create super-soldiers, personalize medicine, increase human performance, improve human gene therapy, and synthesize biology. Innovations such as synthetic biology have created new areas of discovery, outpacing current public health, safety, and security measures.

The world is failing to recognize the multifaceted nature of the biological threat. Advances in biological science and technology can harm us as well as help us. Leaders must recognize that COVID-19 is not the last biological threat we will have to face in our lifetimes—or, perhaps, even this year.

Disruptive technology in the age of disinformation

The new US administration has done much to reestablish the role of scientists in informing public policy, and even more to minimize deliberate confusion and chaos emanating from the White House. Thoughtful deliberation—merely a promise in January 2021—appears to be realized more often today. On the other hand, disinformation fomented outside the executive branch—including from some members of Congress and many state leaders—appears to have taken root in alarming and dangerous ways.

Large fractions of Congress and the public continue to deny that Joe Biden legitimately won the presidential election, and their views on these matters appear to be hardening rather than moderating. Similar trends regarding COVID-related disinformation are apparent around the world, crippling the ability of public health authorities and medical science to achieve higher vaccination rates. Mask-wearing and social distancing are similarly discouraged by disinformation. While we know more now about the role of social media campaigns in taking advantage of vulnerabilities in human psychology and cognition to spread disinformation and societal disunity, the behavior of social media companies has changed hardly at all. Political attacks on institutions that provide societal continuity and store hard-won knowledge about how best to deal with problems continue apace.

In cyber conflict, cyberattackers have grown more audacious. The SolarWinds hack, an attack on Microsoft Exchange that affected millions around the world, and a ransomware attack on Colonial Pipeline (resolved only with the payment of $4.4 million to get the system up and running again) all demonstrate the far-reaching ramifications of cyber-vulnerabilities.

The good news in cyber includes a Biden executive order and other federal government initiatives on cybersecurity that seem to have significant force and momentum behind them and have gone farther than previous orders and initiatives. The expert cybersecurity team the new administration has assembled has the ear of the president. In addition, against all odds, both the UN Open-Ended Working Group and the Group of Government Experts have reached some rough consensus on cyber norms of behavior. (The first group involves representatives from most of the world’s nations; the latter includes the biggest players in cyber.) It remains to be seen whether these norms actually affect the behavior of national actors in cyberspace, but it is better to have these norms in place (or in the process of being formed and agreed to) than not to have them at all.

It also appears that Chinese use of surveillance technology has reached new heights in Xinjiang in the last year. Artificial intelligence and facial recognition systems intended to reveal states of emotion have been tested on Uyghurs in Xinjiang. In the last year, it has also come to light that China is seeking to develop standards for using facial recognition that can be optimized for distinguishing individuals by ethnic group. The potential widespread deployment of these technologies presents a distinct threat to human rights around the world and, therefore, civilization as we know and practice it.

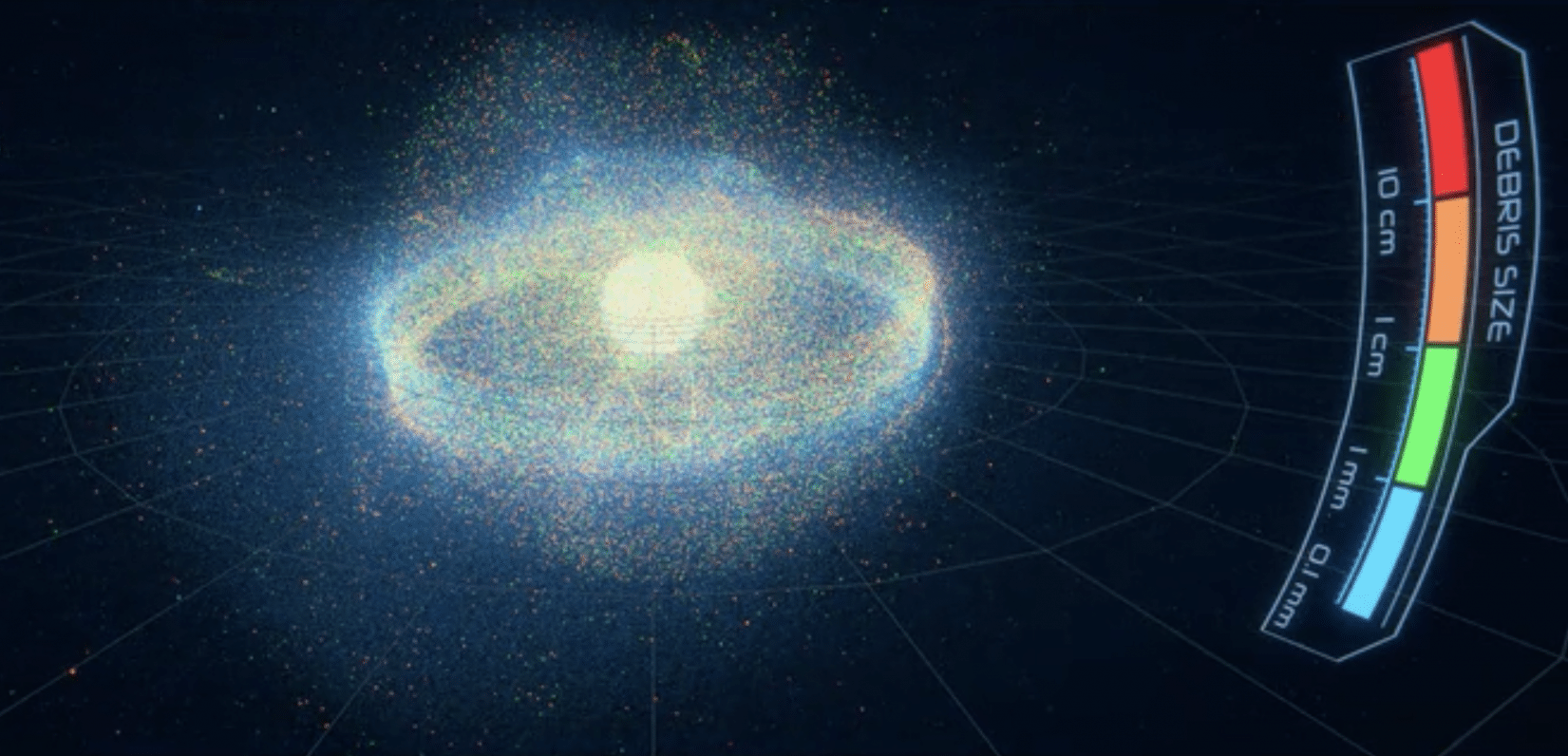

Finally, tensions over military space activity have increased in the past few years. For example, Russia conducted an anti-satellite missile test in November, destroying one of its own satellites and creating a debris cloud that orbited dangerously close to the International Space Station. Russia has also “injected an object into orbit” that subsequently approached another Russian satellite already in orbit in a manner consistent with its use as an anti-satellite weapon. A similar activity has been used to follow a US government satellite. Press reports have suggested that US Space Command is on the verge of disclosing a new anti-satellite weapon. On the other hand, US officials from the State and Defense departments were reported to be drafting language for a binding UN resolution regarding responsible behavior in space. If approved, such language could reduce the likelihood of space incidents taking place.

Practical steps to move the world away from catastrophe and toward a safer world

Last year, we looked forward to the end of the COVID-19 pandemic—but that end is not yet in sight. Leaders in the wealthiest and most advanced countries have not acted with the speed and focus necessary to manage dire threats to humanity’s future.

Our decision to keep the Doomsday Clock at 100 seconds to midnight is a clear warning to the world: We need to back away from the doorstep of doom. Immediate, practical steps to protect humanity from the major global threats that we have outlined are needed:

- The Russian and US presidents should identify more ambitious and comprehensive limits on nuclear weapons and delivery systems by the end of 2022. They should both agree to reduce reliance on nuclear weapons by limiting their roles, missions, and platforms, and decrease budgets accordingly.

- The United States and other countries should accelerate their decarbonization, matching policies to commitments. China should set an example by pursuing sustainable development pathways—not fossil fuel-intensive projects—in the Belt and Road Initiative.

- US and other leaders should work through the World Health Organization and other international institutions to reduce biological risks of all kinds through better monitoring of animal-human interactions, improvements in international disease surveillance and reporting, increased production and distribution of medical supplies, and expanded hospital capacity.

- The United States should persuade allies and rivals that no-first-use of nuclear weapons is a step toward security and stability and then declare such a policy in concert with Russia (and China).

- President Biden should eliminate the US president’s sole authority to launch nuclear weapons and work to persuade other countries with nuclear weapons to put in place similar barriers.

- Russia should rejoin the NATO-Russia Council and collaborate on risk-reduction and escalation-avoidance measures.

- North Korea should codify its moratorium on nuclear tests and long-range missile tests and help other countries verify a moratorium on enriched uranium and plutonium production.

- Iran and the United States should jointly return to full compliance with the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action and initiate new, broader talks on Middle East security and missile constraints.

- Private and public investors should redirect funds away from fossil fuel projects to climate-friendly investments.

- The world’s wealthier countries should provide more financial support and technology cooperation to developing countries to undertake strong climate action. COVID-recovery investments should favor climate mitigation and adaptation objectives across all economic sectors and address the full range of potential greenhouse gas emission reductions, including capital investments in urban development, agriculture, transport, heavy industry, buildings and appliances, and electric power.

- National leaders and international organizations should devise more effective regimes for monitoring biological research and development efforts.

- Governments, technology firms, academic experts, and media organizations should cooperate to identify and implement practical and ethical ways to combat internet-enabled misinformation and disinformation.

- At every reasonable opportunity, citizens of all countries should hold their local, regional, and national political officials and business and religious leaders accountable by asking “What are you doing to address climate change?”

Without swift and focused action, truly catastrophic events—events that could end civilization as we know it—are more likely. When the Clock stands at 100 seconds to midnight, we are all threatened. The moment is both perilous and unsustainable, and the time to act is now.

About the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

At our core, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists is a media organization, publishing a free-access website and a bimonthly magazine. But we are much more. The Bulletin’s website, iconic Doomsday Clock, and regular events equip the public, policymakers, and scientists with the information needed to reduce manmade threats to our existence. The Bulletin focuses on three main areas: nuclear risk, climate change, and disruptive technologies. What connects these topics is a driving belief that because humans created them, we can control them. The Bulletin is an independent, nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization. We gather the most informed and influential voices tracking manmade threats and bring their innovative thinking to a global audience. We apply intellectual rigor to the conversation and do not shrink from alarming truths.

The Bulletin has many audiences: the general public, which will ultimately benefit or suffer from scientific breakthroughs; policy makers, whose duty is to harness those breakthroughs for good; and the scientists themselves, who produce those technological advances and thus bear a special responsibility. Our community is international, with half of our website visitors coming from outside the United States. It is also young. Half are under the age of 35.

Learn more at thebulletin.org/about-us.

The Science and Security Board (SASB) is comprised of a select group of globally recognized leaders with a specific focus on nuclear risk, climate change, and disruptive technologies.

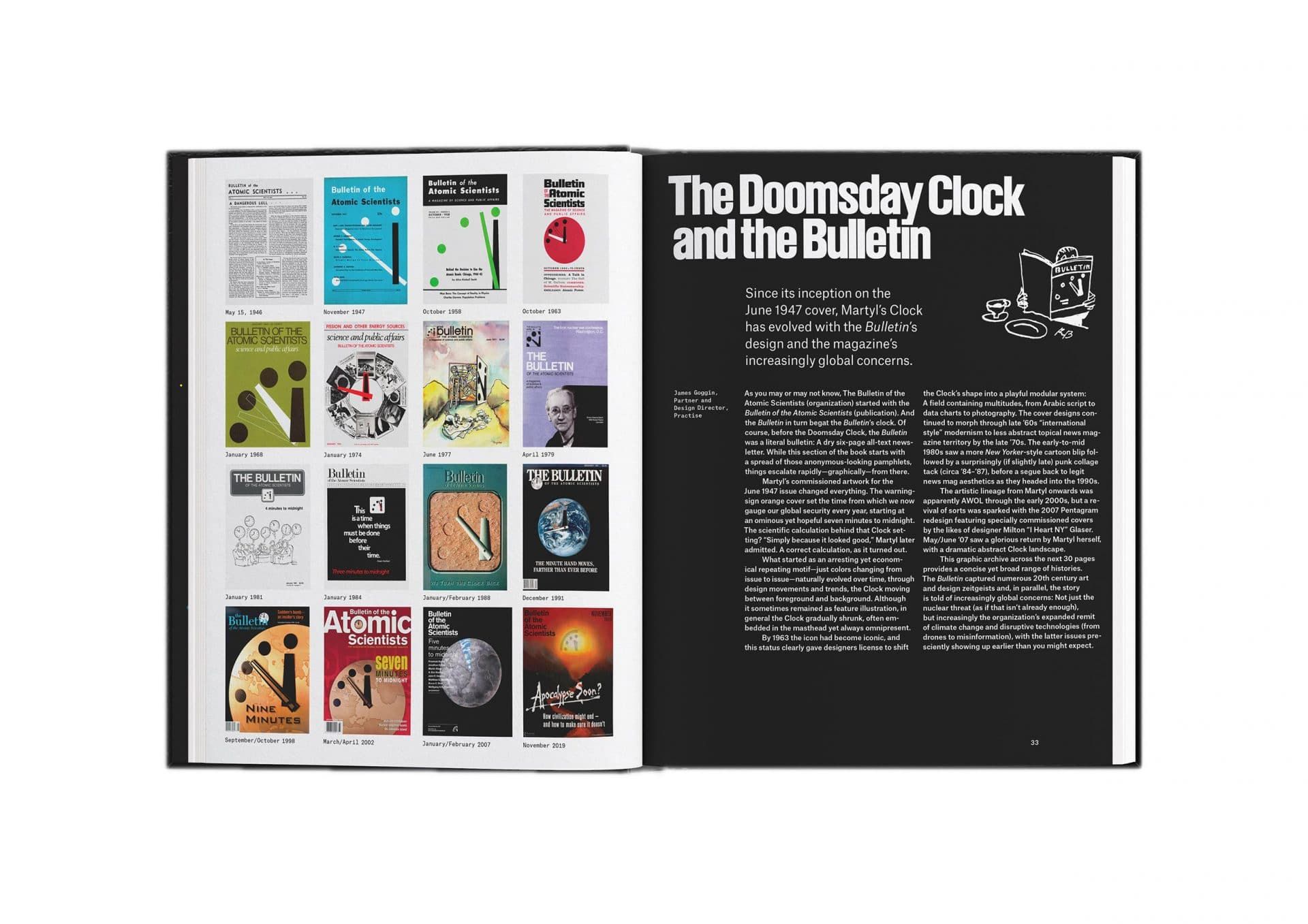

NEW BOOK

The Doomsday Clock at 75

The Doomsday Clock is many things all at once: It’s a metaphor, it’s a logo, it’s a brand, and it’s one of the most recognizable symbols in the past 100 years. It has permeated not only the media landscape but also culture itself. This 75th anniversary coffee table book explores the powerful symbol of the Clock, and how it has impacted culture, politics, and global policy—and helped shape discussions and strategies around nuclear risk, climate change, and disruptive technologies.