Introduction: Can we make overspending on the military politically costly?

By John Mecklin | September 7, 2021

Introduction: Can we make overspending on the military politically costly?

By John Mecklin | September 7, 2021

In my time as editor of the Bulletin, I have learned many ways to kill cocktail party conversation, raising the prospect of apocalypse chief among them. But even the end of the world has a certain fascination about it that the numerical details of defense spending do not. If you want to clear a room anywhere outside of certain small parts of Washington, DC, there may be no better way to start than to utter the words “Pentagon budget.”

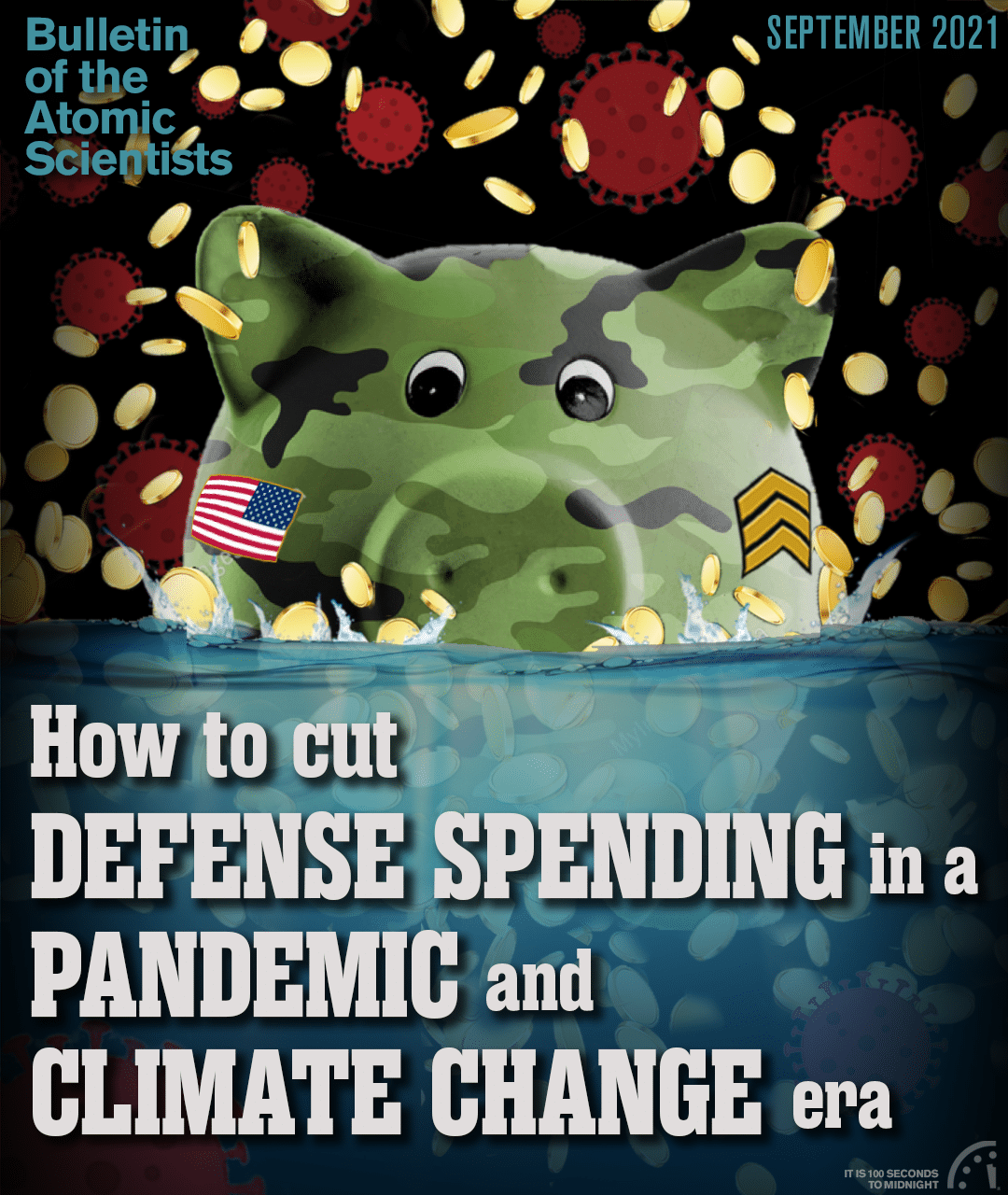

Yes, the mind-numbing, bean-counting aura surrounding defense budgets—the ratios of outlays to gross domestic product, the comparisons in real dollars between this year and that—has long helped protect defense spending from the scrutiny it deserves, in and outside the government. To avoid starting here with military-industrial-complex arcana, then, let me make a simple statement that is, to my way of thinking, undeniable: The countries of the world spend too much on their militaries and too little on climate change, pandemic protection, and other emerging security threats of the 21st century.

The United States is the largest offender in this regard. Current US defense outlays are roughly the size of the defense spending of China, India, Russia, United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, Germany, France, Japan, South Korea, Italy, and Australia—combined. And remember: Many of the countries in that list are US allies.

The unwarranted expansion of the US defense budget since the end of the Cold War has been a bipartisan affair. Republican President Donald Trump’s last bloated defense budget was about $740 billion. Democratic President Joe Biden took over the White House this year and, to the dismay of many in his party, proposed a defense budget increase, to $753 billion. That enormous number wasn’t enough for the Senate Armed Services Committee, which recently threw another $25 billion into the defense pot via an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act, approved, horrifyingly, by a 23-3 vote in a committee split evenly between Republicans and Democrats. (The House Armed Services Committee subsequently approved its own $23.9 billion add-on.)

As I write this introduction, it is not clear exactly how large the next US defense budget will be. But I can confidently predict that it will be huge and full of absurdly costly programs and weapons that are at best unnecessary and often unusable—unless they are used to end civilization. For this issue, I asked five expert observers of US military spending for their views on bringing a measure of sanity to the process by which successive Congresses and presidents produce—almost automatically, with little that resembles probing oversight or even rational discussion—ever-larger US defense budgets.

Many of the least usable and most dangerous systems in the US military involve nuclear weapons, whose entire rationale revolves around their not being employed. I spoke with Tom Collina, director of policy at the Ploughshares Fund, about his efforts, in concert with former Defense Secretary William Perry, to eliminate or at least delay the proposed replacement of the US fleet of intercontinental ballistic missiles with a new set of nuclear-tipped missiles known as the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent. It’s a program with a total life-cycle cost that could exceed $260 billion, and many experts feel the new missiles are unneeded to deter other nuclear powers from attacking the United States and are also, in fact, uniquely destabilizing and dangerous. As Collina notes, Congress shows no inclination to rein in the GBSD program or seriously question its utility.

My conversation with Diane Randall, general secretary of the Friends Committee on National Legislation, dealt in large part with her organization’s efforts to lobby Congress on a range of issues that include the defense budget and nuclear weapons. Randall had a great many interesting (if sometimes distressing) things to say about the enormous momentum of the forces pushing the United States toward ever-increasing defense budgets, including this: “The fact is that there is bipartisan support for continuing excessive defense spending in the United States. Until we can begin to have more voices calling for actual reductions and cuts—more voices in Congress and from people around the country—it will be hard for [Congress] to say no.”

In her piece for this issue, “The United States needs to cut military spending and shift money to two pressing threats: pandemics and climate change,” Mandy Smithberger of the Project On Government Oversight details a litany of egregious Pentagon spending disasters, some of which were shocking even to me, a veteran observer of the many creative ways in which governments waste money. (I guess “spending $46 billion on programs that were ultimately cancelled” will have that effect, no matter how hardened the journalist.) The first line of Smithberger’s article is, I think, a wise statement of the most important lesson of this era: “The last year has made one fact quite clear: Spending huge amounts of money on defense has little to no impact on whether a country will be able to effectively protect its people and its economy from a pandemic.”

Lawrence Korb knows a thing or two about defense spending; he was an assistant secretary of defense from 1981 through 1985, during which time he administered some 70 percent of the US defense budget. His disappointment with the unrestrained defense budget that President Biden presented this year is detailed and palpable. “The budget President Biden has embraced is higher in real terms than what the United States was spending during the Reagan administration and the Korean and Vietnam wars,” Korb writes. “Although I think it unlikely that Biden will present a defense budget next year that makes him our next liberal president, I certainly hope—at a time when a pandemic and climate change demand American attention and funding—that he does.”

If the United States ever gets serious about shifting money from defense and into programs that provide more public health and welfare bang for the buck, it could profitably start by considering the plan put forward by MIT expert Barry R. Posen in “A new transatlantic division of labor could save billions every year!” Posen’s proposal would realign the NATO “division of labor” on defense in a way that plays to the strengths of the European and American militaries and save the United States $70 to $80 billion a year. It is a thoughtful and reasonable plan that ought to—but I suspect will not—get a serious hearing in Congress. As Posen notes, “NATO is a venerated alliance in the US national security establishment, and supporters of the alliance will oppose this change, even though it leaves the alliance intact and the United States deeply engaged.”

Although there seems little prospect for reduced US defense spending in the next year or two, it is at least plausible that the cost of dealing with climate change, pandemic protection, and a host of other emerging global threats will at some point bring the US and other governments to eye military budgets more carefully. But my discussions with and readings of the experts featured in this issue suggest to me that gross overspending on US defense, at the expense of more productive and useful enterprises, will not end until the politics that surrounds defense spending changes.

Right now, the enormous political and economic incentives to increase defense spending—jobs in legislative districts and states, campaign contributions to House and Senate coffers, avoidance of being labelled “soft on defense”—outweigh any political downside. Changing the national conversation on this potentially room-clearing subject will require that those of us in the news media be more creative in finding ways to engage more readers and viewers with it. It will also require those who want less money poured into tragi-comic ratholes like the F-35 fighter to find ways to make support for these boondoggles costly—to the congressmen and -women who keep them doggling. During our conversation, Collina said, “What we need them to understand is there are risks to their political futures.” When he said it, one word came to my mind: exactly.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: F-35, NATO, POGO, Pentagon budget, defense cuts, defense spending, ground-based strategic deterrent

Topics: Uncategorized

The amount we spend on defense budgets has been outrageous for longer than I have been alive. What is even more outrageous is how so much of it is wasted. Every where you look in the DOD ridiculous, obvious mismanagement of our resources is evident. But it is done with impunity because they know no one will stop the madness.