Russia’s alleged bioweapons claims have few supporters

By Jez Littlewood, Filippa Lentzos | October 11, 2022

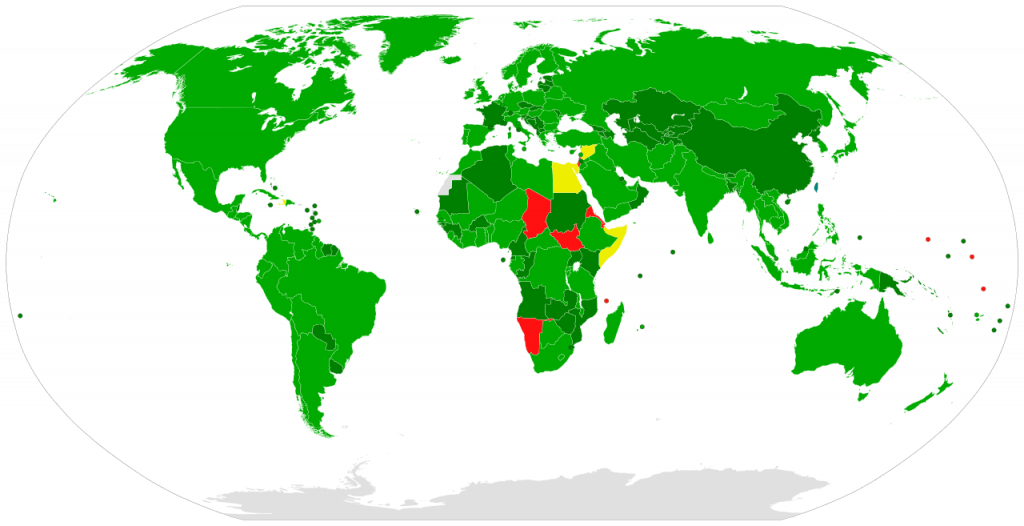

For the fourth time this year, Russia accused the United States and Ukraine of being in non-compliance with the Biological and Toxins Weapons Convention (BTWC)—and once again found little support for its allegations. At the conclusion of the Article V Formal Consultative Meeting in September, no other state formally accused these two nations of non-compliance. Russia stands alone in its allegations, with limited support from eight other states. In contrast, more than five times as many backed the United States and Ukraine in rejecting the allegations; the meeting ended with a procedural report that noted no consensus regarding the outcome.

Since the treaty’s adoption in 1975, this is only the second time that a formal meeting was called to consult and cooperate on an alleged violation. The first was in 1997 when Cuba asserted that the United States had disseminated insects to attack its agriculture. The latest meeting may have ended without a decision, but it left little doubt about how isolated Russia is in making these claims.

Reporting on the meeting emphasized that 35 states backed the United States in rejecting the allegations, while few states backed Russia. (It’s important to note, however, that those other states provided limited support and largely only endorsed the consultation process, the legitimacy of Russia’s right to request the meeting, and repeated some of the questions Russia was asking about the United States and Ukraine.) None joined Russia in formally alleging non-compliance.

Triggering Article V represented an escalation of Russia’s years-long disinformation campaign on biolabs and what it portrays as nefarious “US military biological activities.” After its failure to gain traction at the United Nations Security Council meetings earlier this year, Russia initiated bilateral consultations with the United States in June. But just two weeks later it requested a formal consultative meeting.

The closed-door nature of the meeting meant that it risked becoming an opaque process. But states could request national positions and other documents be published as official working papers. Many have since done so; consequently, there are more than 70 working papers currently available, including documentation related to Russia’s allegations, the rebuttals of the United States and Ukraine, and national statements about the process and the allegations themselves. Compared to the 1997 meeting, which officially has only its procedural report and a follow-up letter available, the 2022 meeting was significantly more transparent.

At the meeting, Russia decided to focus on four issues—two directed at the United States and two at Ukraine. Russia claimed that a patent issued in the United States involved potential applicable usages for biological warfare and that the funding provided to Ukraine by the United States was carried out in violation of the Convention. Regarding Ukraine, the allegations revolved around claims that collections of bacterial cultures in Ukrainian laboratories were of little relevance to the predominant endemic diseases in the country and that a licensing request to acquire a particular Turkish drone that Russia suggested could be fitted with spray tanks posed “a real threat of large-scale use of biological weapons on the territory of the Russian Federation.”

The United States and Ukraine refuted the claims through statements and presentations, while other states expressed their views based on what they heard in statements and read from available documents. In total, 65 states expressed a view: Russia, the United States and Ukraine whose positions were clear before the start of the meeting and 62 states in national or joint statements.

Eight states—Belarus, China, Cuba, Iran, Nicaragua, Syria, Venezuela, and Zimbabwe—stopped short of claiming non-compliance but supported Russia’s right to use the consultation process and indicated Russia’s allegations left questions for the United States and Ukraine to answer. China went further than most, implying that the United States should recognize Russia’s concerns, set an example of compliance, make more comprehensive efforts to respond to posed questions, and provide a clear answer to the international community. Appended to its statement, China listed additional questions for the United States.

Furthermore, China was at the forefront of supporting Russia’s call for follow-up actions that might include lodging a non-compliance complaint with the UN Security Council under Article VI of the Convention. Belarus was the other supporter, focusing its questions on the patent issue for a delivery system. Its view is that possible non-compliance may arise around this patent. As the United States representatives noted, this issue had been explored in 2019 bilateral discussions with Russia and granting an individual patent in the United States does not mean the government has any interest in such systems, nor does it circumvent US law that prohibits manufacture of a delivery system to use biological weapons.

Compared to China and Belarus, others were more circumspect. Russia has vigorously defended Syria in the Security Council over its use of chemical weapons and in the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, but Syria returned the favor only with a fawning response about the professionalism of Russia’s presentations and the technical details of the documents. Its only substantive claim was that the United States and Ukraine had made no serious attempt to answer the questions. Iran could only muster support for Russia’s right to request the meeting and suggested that the United States should provide clarifications in a transparent manner. Iran’s support was so lukewarm that it did not even align itself with the joint statement by Belarus, China, Cuba, Nicaragua, Russia, Syria, Venezuela and Zimbabwe, which indicated there remain unresolved questions and called for a follow-up process.

Another category of responses emerged from 42 states that unambiguously rejected the allegations. Sweden called for Russia to “cease their unfounded allegations and stop its disinformation campaign” and Ireland urged an end to the misuse of consultation procedures that undermine multilateral disarmament and non-proliferation agreements. The Czech Republic spoke on behalf of all European Union member states and others who asked to be aligned with it, to categorically reject the Russian claims. Others, such as Norway, “heard nothing—or read nothing—that even comes close to substantiating such allegations.” The collective message of these states was encapsulated by Switzerland in a statement noting “a firm view that the allegations made have not been substantiated; that the conclusions drawn are neither convincing nor credible; and allow in no way to draw the conclusion that the obligations of the United States and Ukraine under the BWC have been violated.”

A group of 12, including Armenia, Brazil, Chile, India, Mexico, Nigeria, South Africa and Uzbekistan, neither supported nor rejected the allegations. Some, such as South Africa and Chile, hinted at the misuse of the process and emphasized that peaceful cooperation to build the capacity of health systems help states identify and manage disease outbreaks. This muted criticism was likely a signal that Russia’s claim that the United States was using peaceful cooperation as a guise to support weapons programs was unwelcome and risked contaminating all cooperation in the biological field. The emphasis on peaceful cooperation in biology under Article X of the BWC was also a signal of support for both the United States and Ukraine. Prior to the meeting, the United States, Armenia, Georgia, Iraq, Jordan, Liberia, Philippines, Sierra Leone, Uganda and Ukraine had issued a joint statement highlighting their collective contribution to reduce global health security threats.

States in this category also used the meeting and its challenges as a platform to reiterate their support for biological disarmament and their preference for a verification mechanism. In their view, only a verification mechanism is capable of resolving the issues Russia’s questions purported to address. This support for verification will have implications for the ninth review conference in November and December of this year.

Finally, there were 30 states who were physically present but not engaged in the process via national statements or other available documents. This group, which comprised one-third of attendees, may have made their views known privately and chose to avoid expressing them publicly out of realpolitik concerns. As both Germany and Russia stated, for different reasons, this silence matters: Russia interpreted it as meaning only the allies of the United States rejected its claims, whereas Germany asserted states cannot remain silent and on the sidelines if they want to uphold the authority of the Convention.

Taken together, the statements reveal how little traction Russia’s allegations have with others. Even among those aligning with Russia some of the support is simply a convenient intersection with other issues. China’s interest in the US Defense Department’s funding to laboratories escalated after the outbreak of the pandemic as a way to shift the narrative on the origins of COVID-19. For Syria, the biolabs narrative is an opportunity to support its most vocal defender (Russia) and criticize its more vocal adversary (the United States) with regards to its multiple uses of chemical weapons. Based onvoting in the United Nations regarding Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and how states voted on key decisions around Syria’s violations of its obligations under the Chemical Weapons Convention, it was expected that some combination of Belarus, China, Cuba, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Iran, Venezuela, and Syria would back up Russia’s claim. North Korea did not attend the meeting, but Nicaragua offered some procedural support to Russia and Zimbabwe aligned itself with the Russian-led joint statement calling for a follow-on process.

What does it all mean? The outcome of the meeting has procedural and substantive meanings and knock-on effects. In procedural terms, the consultation meeting process worked as intended: it enabled states to formally share views on the allegations. In addition, despite being a closed meeting, the release of tens of documents provided a degree of transparency few expected when the meeting was announced in July. In 1997, when Cuba’s allegation was addressed, it took four months to find out that 13 states submitted views and that a definitive conclusion on Cuba’s allegation was not possible due to the technical complexity of the matter and the time between the incident and the consultative meeting. This time, the views of more than 60 states and detailed information about the allegations and the rebuttals to the accusations were accessible within days. Whether intended or not, Russia, the United States and Ukraine have set a benchmark for release of information and evidence that substantiates and rebuts claims to a wider audience.

This approach will have implications for any future allegations and how states respond to questions around certain activities. It is in stark contrast to Syria’s response to questions around its non-compliance with the Chemical Weapons Convention, Russia’s <href=”#post-heading” >obfuscation around its use of chemical weapons for assassinations, Iran’s unwillingness to address remaining questions from the International Atomic Energy Agency and other states on possible military dimensions of its nuclear activities and China’s rejection of the World Health Organization plans for further investigation into the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Despite Russia’s isolation, the formal consultative meeting will probably not be the end of the allegations. Russia is not likely to be dissuaded by its lack of support or the fact that during the three Security Council meetings on this topic earlier this year, the head of disarmament at the UN repeatedly noted that there are no signs of biological weapons in Ukraine. There is a high likelihood that Russia will pursue a follow-up process at the Security Council, possibly with the support of China and others based on the joint statement, perhaps just weeks or days before the review conference. The knock-on effect is that Russia’s rejected allegations may continue to prevent necessary focus on strengthening the Convention.

A final implication of the meeting is an impression that most states parties very clearly prefer to avoid discussion of compliance issues. Less than half of eligible states attended the meeting and a third of the participants were silent. This level of non-involvement with serious issues, even when most consider Russia’s allegations to be broad, vague, and generally viewed as lies and outlandish attempts to shift attention from its illegal invasion of Ukraine, suggests that the majority of states are simply uninterested in the hard work of keeping the world free of biological weapons. Such disinterest is a boon for disinformation and a real challenge for anyone seeking to strengthen the Convention.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: BTWC, Russia, Ukraine, biosecurity, bioweapons

Topics: Biosecurity