Hiroshima and Nagasaki: The many retrospectives

By Dan Drollette Jr | August 8, 2014

Sixty-nine years ago, at 8:15 in the morning on August 6, the first atomic bomb exploded over Hiroshima. Three days later, another bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. Estimates vary as to the number of people who died in those blasts, but the figure of at least 130,000 deaths for Hiroshima seems to be generally accepted, with another 70,000 for Nagasaki as of surveys conducted in November 1945.

With the anniversaries of those events have come many news and comment stories in the press. But how best to put the bombings into perspective, especially after so much time has passed? The problem—to loosely paraphrase Joseph Stalin, no stranger to death on an industrial scale—is that “one death is a tragedy, while a million deaths is a statistic.” (This is particularly true when dealing with dry analytical reports about security, which inevitably use phrases like “collateral damage,” “kilotons,” and “battlefield scenarios”—masking the fact that there are large numbers of very real human lives involved on the receiving end of a nuclear weapon.)

Consequently, some of the most powerful and compelling articles about the atomic bombing bring things back to the individual, dealing with just a single person and the most intimate, small details of his or her life at the moment of the bombing, as shown in this BBC multimedia piece on Hiroshima survivor Shinji Mikamo. For example, after the blast, while looking through the ruins of his family home, Mikamo found his father’s watch, which had stopped at precisely 8:15 am. In Mikamo’s words: “The unimaginable intense heat that reached several thousand degrees Fahrenheit from the blast had fused the shadows of the hands into the face of the timepiece, slightly displaced, leaving distinct marks where the hands had been at the moment of the explosion. It was enough to clearly see the exact moment the watch stopped.”

Other articles, such as this one in the Washington Post, tried a different approach to bring home the horror of the blasts. It focuses on a large and well-known symbol of the bombing: the dome of a concrete-and-steel structure that was one of the few buildings to survive the atomic blast in 1945. Now known as the Hiroshima Peace Memorial, the building has become the epicenter of yearly memorials and services to remember the victims. Through the use of the article’s slide show, readers can see the dome as it looked immediately after the blast, and again over the years, until today. The memorial itself contains a museum with artifacts, exhibitions, and first-person survivor, or hibakusha, accounts.

There is something about seeing or hearing something first-hand, on-site; it really makes an impression. Knowing this, the mayor of Hiroshima asked leaders of nuclear-armed nations to see for themselves atomic bomb-scarred cities. “If you do, you will be convinced that nuclear weapons are an absolute evil that must no longer be allowed to exist,” Kazumi Matsui was quoted as saying by ABC News.

Not that there is anything wrong with standing back and taking a look at the big picture. Some media outlets have used the anniversary as an occasion to pause and think about nuclear weapons, such as this Time magazine piece by Harvard's Elaine Scarry, which notes: “An appropriate way to reflect on these events might be to contemplate our current nuclear arsenal and ask why it is being kept in place. The U.S. has by far the most powerful arsenal on Earth. Our 14 Ohio-class submarines together carry the equivalent of at least 56,000 Hiroshima blasts. These ships are not a remnant of the Cold War. Eight were made after the opening of the Berlin Wall during the presidencies of George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton.”

Over the years, of course, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists has published its own rich lode of material—from all viewpoints—on the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Highlights include The Sanctification of Hiroshima, a 1985 piece in which a physicist affiliated with the Manhattan Project supports the Hiroshima but not the Nagasaki bombing.

Meanwhile, John E. Coggle’s 1982 review of the 600-page book Hiroshima and Nagasaki: the Physical, Medical, and Social Effects of the Atomic Bombings, by The Committee for the Compilation of Materials on Damage Caused by the Atomic Bombs hews to a different perspective. Drawing on his background as a medical doctor, Coggle went over the informative, technical prose and the 200 statistical tables, diagrams, maps, and photographs that graphically depict the effects of thermal radiation, the shock wave and ionizing radiation, short-term and long-term biological effects, and the social and psychological impacts. Coggle used the phrase “encyclopedia of horror” to describe the book’s un-nerving but necessary content, noting: “As a radiation biologist one sees the words ‘Hiroshima and Nagasaki’ quite frequently but only in the arid academic context of science…”

At the end of the day, it can be worthwhile on the Hiroshima and Nagasaki anniversaries to think about the personal and the emotional—while keeping such clinical data in mind and ready to hand when it is necessary to debate proponents of ideas such as “battlefield nuclear weapons,” “limited nuclear war,” and the use of select nuclear strikes as a form of “de-escalation.”

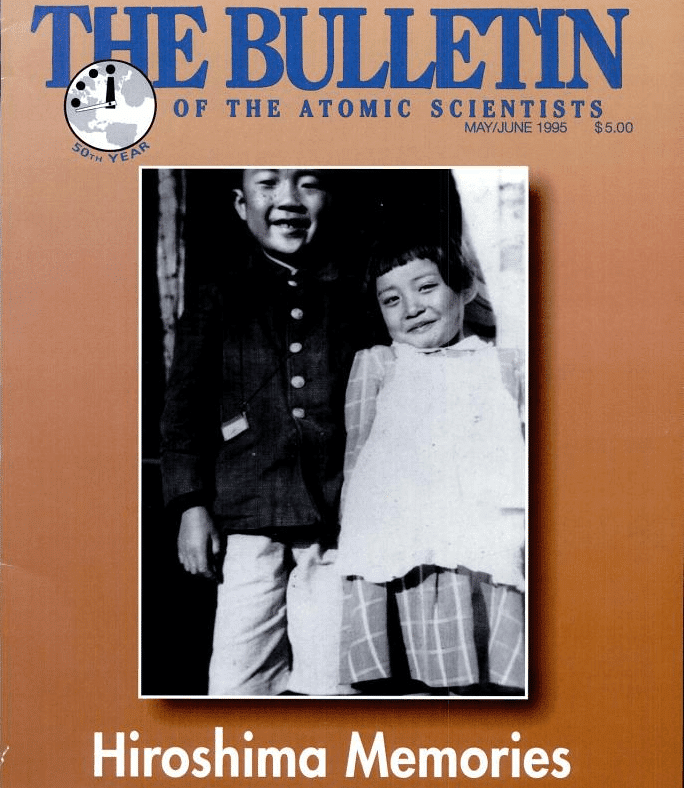

Therefore, perhaps the most compelling of the stories in the Bulletin archive is a first-person recollection, Hiroshima Memories, by Hideko Tamura Friedman, who was just a young girl back on August 6, 1945. After moving to the United States and becoming a therapist in private practice and a part-time social worker in the Radiation Oncology Department at the University of Chicago Hospitals, Hideko excerpted this 1995 article from a longer, unpublished manuscript she was working on.

Hideko describes how she was reading a book when “a huge band of white light fell from the sky down to the trees.” She jumped up and hid behind a large pillar as an explosion shook the earth and pieces of the roof fell about her.

Hideko survived; some members of her family did not. “My father,” she wrote in in a heart-rending statement of fact, “brought Mama’s ashes home in his army handkerchief.”

Editor’s note: The Bulletin’s archives from 1945 to 1998, complete with the original covers and artwork, can be found here. http://books.google.ca/books?id=-wsAAAAAMBAJ&source=gbs_all_issues_r&cad=1. Anything after 1998 can be found via the search engine on the Bulletin’s home page.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Analysis, Nuclear Weapons