Kazakhstan: A leader in global nuclear policy?

By Kiryl Puchyk | March 2, 2017

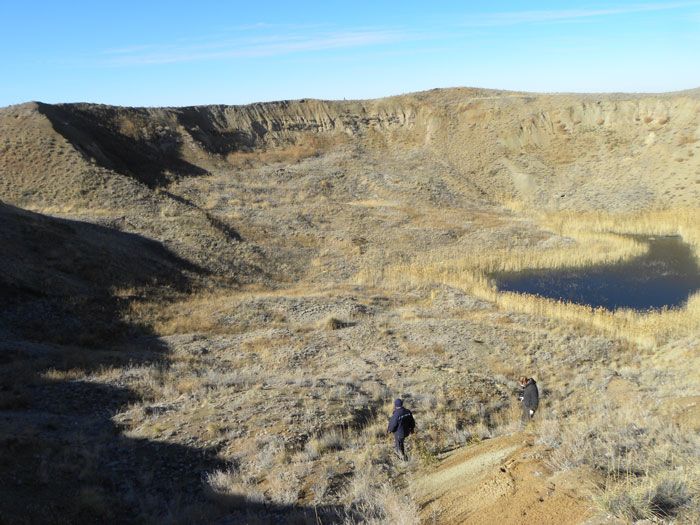

Some residents of the small village of Koyan (a pseudonym) walk inside a nuclear crater. Photo copyright Magdalena Stawkowski.

Some residents of the small village of Koyan (a pseudonym) walk inside a nuclear crater. Photo copyright Magdalena Stawkowski.

Cases of voluntary nuclear disarmament are fairly rare. Along with Belarus, Ukraine, and South Africa, however, Kazakhstan is on the list of former atomic nations. Having once been at the heart of the Soviet nuclear program, the country closed its infamous Semipalatinsk Test Site in 1989 and transferred its atomic arsenal to Russia in the following years. Modern Kazakhstan has in fact rebranded itself as a supporter of nonproliferation policies and peaceful atomic energy. And as this Russian language article on the Carnegie Moscow Center site details, the role of this Central Asian republic should not be underestimated.

Kazakhstan often appears in news as a top uranium producer. In fact, since the country’s decision in January to reduce the production of uranium by 10 percent, the world price of uranium ore increased 30 percent. In this context, Iran’s plans to buy 950 tons of uranium seems an appealing deal for Kazakhstan. For the Iranian side, it is an opportunity to continue developing its energy sector without violating the 2015 nuclear agreement struck with six world powers.

Another Kazakhstan project that is likely to draw attention in 2017 is the Low Enriched Uranium (LEU) Bank. Owned and controlled by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), it will be located at the Ulba Metallurgical Plant in Oskemen. As the only volunteer for hosting the LEU bank, Kazakhstan faced no competition. But the country takes this project seriously. Potentially, it can discourage aspiring nuclear powers from developing their own nuclear fuel cycles and thereby limit the proliferation of nuclear weapons. From a more pragmatic standpoint, however, the LEU bank is an opportunity for Kazakhstan to increase its influence in the IAEA and promote its image as a nonproliferation movement leader.

That image seems to constitute a significant part of Kazakhstan’s international agenda. For example, in 2013 the country hosted two talks dedicated to the Iran nuclear crisis. Two years later, Kazakhstan and Japan were nominated to facilitate the ratification of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). And as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council for 2017-2018, the country has declared that nuclear safety will be one of its priority areas. Unfortunately, whatever Kazakhstan’s aspirations and ambitions might be, there is only so much it can do in the realm of nuclear policy. Though its diplomatic and practical contributions can increase the country’s prestige, they are unlikely to put an end to proliferation or push current nuclear powers to disarm.

Publication Name: Carnegie Moscow Center

To read what we're reading, click here

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Nuclear Energy, Nuclear Weapons, What We’re Reading