Florence and the 5 stages of climate change acceptance

By Dan Drollette Jr | September 21, 2018

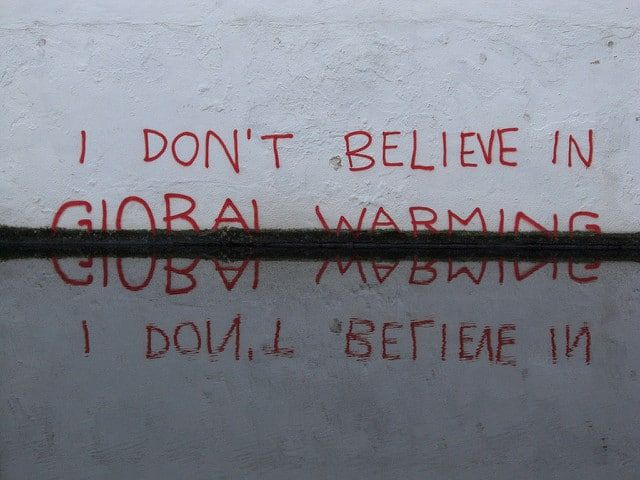

Graffiti in London, possibly the work of noted street artist Banksy. Image courtesy of Matt Brown/Pixabay

Graffiti in London, possibly the work of noted street artist Banksy. Image courtesy of Matt Brown/Pixabay

Now that we’ve gotten through Hurricane Florence, Americans should be completely up to speed when it comes to dealing with disasters that have been amplified by anthropogenic climate change, right?

Not so fast.

Judging from the various news stories in the past year—since Hurricane Irma devastated the Caribbean and the Florida Keys—the United States seems to be stuck in a rut, responding to climate disaster with all five of the chronological stages of grief—simultaneously. These stages are often labeled with the acronym DABDA, meaning denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance, and memorably summed up in this episode of The Simpsons.

Substitute the word “amnesia” for “anger,” and the parallels are striking.

Denial: The Guardian just ran a story titled “ ‘It’s hyped up’: Climate change skeptics after Hurricane Florence.” According to the author, while scientists say global warming is behind the increase in the number and intensity of severe storms, many who face them don’t think humans are the problem.

Amnesia: “We have an incredible capacity for amnesia and denial in this country,” Julie Rochman, head of the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety, told Bloomberg last March. (Yes, that’s right: in March, long before the current hurricanes.) In a telling example, the institute examined building policies in 18 Atlantic and Gulf Coast states and found that despite the increasing severity of natural disasters, many of those states have relaxed their approach to building codes—or have yet to impose any whatsoever. It’s all summed up in the article’s headline: “As Storms Get Stronger, Building Codes Are Getting Weaker.”

Bargaining: Another Guardian story (“Why people stay: in North Carolina it’s about roots, memory, and family”) points out that often, people in flood-prone areas have a good idea of the risks they take by living there, but are too invested to leave—and they also hope that they can make a deal with fate, by doing things such as stocking up on food, water and building supplies, moving boats to sturdier docks, and counting on being able to ride out the storm in the nearest hefty building on somewhat higher ground.

Depression. Some folks have a fatalistic attitude, seeing themselves as stuck between a rock and a hard place. As one Florida-based writer put it in the Washington Post in the middle of the 2017 hurricane season: “…Florida has only two main roads: interstates 95 and 75. They are parking lots, and have been for days. People are sitting in their vehicles, completely stopped on four-lane highways, running out of gas. There are no exits on these roads for scores of miles at a time. Once you get on a Florida highway, you are not getting off. You’re stuck. So, my family’s choices are: We stay here in our flimsily built house, made of sheet rock and plywood; or we hop on an unmoving highway and risk running out of gas closer to the coast, with only our car for protection.”

Acceptance. The New York Times’ “Climate Fwd” newsletter took a very hard-headed and pragmatic approach, essentially saying that we better accept the fact that human-aided-and-abetted climate change is here, and we’d better deal with it:

“And while we’re thinking about hurricanes, here’s what you can do to prepare for flooding in your own back yard, whether from hurricanes, inland flooding, or other disasters. The first thing you need to know about flooding is whether your home is in a risky place. The simplest way to find out is to check FEMA’s database of flood maps, where you can type in your home address and see your degree of risk…”

Climate Fwd goes on to say: “Beyond knowing where you stand, you should know how to run—that is, how to evacuate in case of emergencies. Getting to safety in case of a hurricane, inland flood, forest fire, or other emergency takes careful planning beforehand. FEMA has good guides at www.ready.gov for getting away from it all. Some of the advice includes knowing your evacuation routes, and preparing a “go bag” of food, water, and supplies, as well as a cache of copies of personal documents like IDs and insurance records.”

“We hope it doesn’t happen to you! But better safe than, well, you know.”

Publication Name: The Guardian

To read what we're reading, click here

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: climate change, climate denial, global warming, hurricanes

Topics: Climate Change, What We’re Reading