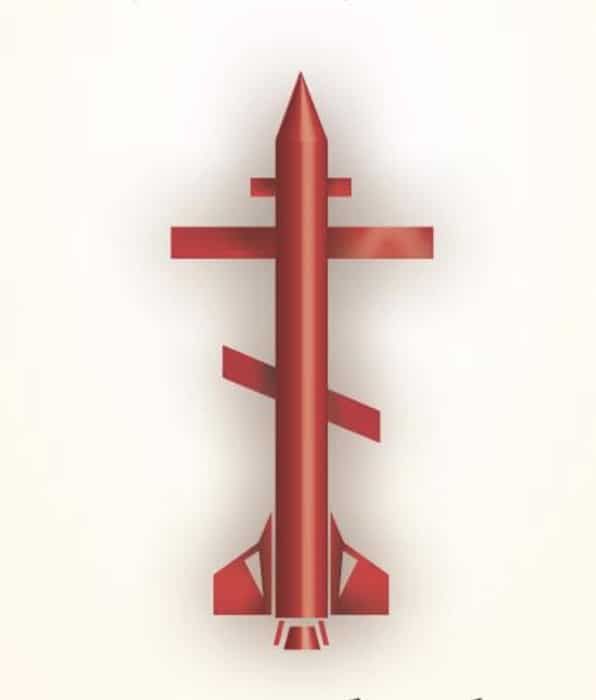

Blessing the holy ICBMs: The Russian Orthodox Church and Putin

By Robert E. Berls Jr. | June 19, 2019

Image courtesy Russian Nuclear Orthodoxy

Image courtesy Russian Nuclear Orthodoxy

Russian Nuclear Orthodoxy: Religion, Politics, and Strategy (Stanford University Press, 2019) by Dmitry Adamsky, a professor at the Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya university in Israel, is a penetrating analysis of the growing influence of the Russian Orthodox Church in Russia’s nuclear world—both in the military and the scientific communities. This excellent scholarly work is well-researched and extensively documented. It shows how the Russian Orthodox Church has penetrated and integrated itself into the Russian Armed Forces and even some of the closed nuclear cities—to the point where priests bless new nuclear missiles. Indeed, to some extent, Russian Orthodox priests have taken over the role formerly held by political officers during the Communist period: They keep an eye on the spiritual purity of the troops, glorify the military, and ensure the reliability of the soldiers during combat.

In some ways, the priests even go beyond the old Soviet military kommissars, reassuring recruits that there is nothing immoral about following orders to launch nuclear missiles and protect the sacred motherland. (Ironically, some nuclear weapons research and development sites were built on holy land confiscated by revolutionary Russia from the church.)

Clearly, throughout much of Russian history, the relationship between the Russian Orthodox Church and the Russian state has been close but not always amicable. The state has usually been the dominant partner, but there have been instances in the past when the Russian Orthodox Church challenged the state and significantly influenced state policy. Czar Ivan the Terrible’s very tumultuous relations with the Russian Orthodox Church had a substantial impact on the course of Russian history—as did, much later, the bizarre influence of the errant monk Rasputin on Emperor Nicholas II’s wife Alexandra, and consequently on the Emperor himself. Under Emperor Nicholas I in the early 19th century, the symbiotic relationship between church and state reached new heights. Church-state relations reached their lowest point following the Bolshevik Revolution and the establishment of an atheist state. During more than 70 years of Soviet rule, the Russian Orthodox Church barely survived.

How things have changed! Since the Soviet Union’s collapse, the church has been aggressively reasserting its authority and role in Russian society.

The state under Vladimir Putin has encouraged the rise of the Russian Orthodox Church but has drawn clear lines of authority to ensure that the church’s position in society does not exceed what is useful to the Kremlin and does not challenge state policies. Vladimir Putin has demonstrably identified his regime with the Russian Orthodox Church to such an extent that his policies appear to share certain features with Nicholas I’s doctrine of “Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality.” It would have been helpful if Adamsky had provided background to the important historical relationship between the Russian Orthodox Church and the Russian state so that the reader could better understand the context of Adamsky’s superb analysis and his extensive narrative of how “… a formerly outcast religion became supported by the state and wormed its way into the most significant wing of one of the most powerful military organizations in the world… within a very short span of time.”

Adamsky devotes much of his book to an explanation of the impact of religion on strategy in Russia. He explores what he calls “the unprecedented role of the Orthodox faith in Russian identity, politics, and national security” and focuses on the bond that has emerged between the Kremlin, the Russian Orthodox Church, and the nuclear weapons community. As for the development of nuclear doctrine and policy, the author maintains that the state retains its monopoly of authority in this area. The church remains supportive of the Kremlin’s nuclear use policy, arms control stance, and weapons acquisition programs; it does not voice a separate position on these issues. Nor does it engage—like many Western churches—in discussions of theoretical and strategic-operational issues regarding nuclear weapons.

Adamsky explains in much detail how the Russian Orthodox Church has greatly increased its physical presence among the military and the nuclear scientific communities. We learn about the growing presence and influence of the Russian Orthodox Church clergy within military units; the Russian Orthodox Church’s aggressive program of building churches on military installations, within closed nuclear cities, and at government facilities (even Rosatom and the Federal Security Service have churches on the grounds of their headquarters); and the blessing and sprinkling of holy water by priests on missiles, tanks, and every imaginable piece of military equipment, military exercise, and troop deployment.

The question remains how has the expanded presence of the Russian Orthodox Church within the nuclear community actually impacted the members of these communities and influenced their work in a meaningful way. Adamsky admits that among some Russian defense intellectuals and security experts there is a degree of skepticism regarding the magnitude of religiosity within the Russian strategic community. It would be interesting if Adamsky had delved more deeply into this question so that the reader could have a better understanding of how members of Russia’s nuclear community personally react to the mounting influence of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Nevertheless, Russian Nuclear Orthodoxy is a seminal work on a very important topic. I urge readers to study this well-researched book in order to gain important insights into Russian church-state relations and their impact on the Russian nuclear community. This is an issue that merits continued close observation and further investigation.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Putin, Russia, nuclear use policy, nuclear weapons

Topics: Book Review, Nuclear Weapons

It’s already horrible for any government to exalt weapons, but having clergymen bless the means of destruction (as the pope did when Mussolini’s Italy invaded Ethiopia) is especially dangerous.

At this point, I don’t know what’s gonna bring down civilization first: global warming or a nuclear holocaust.

From this review: “The question remains how has the expanded presence of the Russian Orthodox Church within the nuclear community actually impacted the members of these communities and influenced their work in a meaningful way. ” But Adamsky does present a detailed picture of how the most important actor in the hierarchy has been impacted: V. Putin himself. It is fairly hair-raising to learn that the bare-chested bear of Russia has undergone a very serious religious transformation in the last two decades (and unrelatedly [?] divorced his wife and embraced bachelorhood). Adamsky’s book, and now an adapted article in Foreign… Read more »

What part of “Thou shall not kill” don’t they understand?

This is a typical move by empirical powers since the Babylonian Empire. The Dead Sea Scroll community made fun of the Romans for praying to their swords.

Sadly, I’ve seen soldiers in uniform with the flag and weapons of war projected on the screen while people sang military hymns in *American* churches in the US on the Fourth of July and on Veterans Day.

Christianity is about a kingdom of the heavens, not made by human hands.