A “critical” battle over uranium mining in the Grand Canyon area

By Dawn Stover | October 30, 2019

When water pumped out of the mineshaft at the Canyon Mine south of Grand Canyon National Park threatened to overflow the onsite containment pond, the uranium mine’s operator began misting the water into the air with water cannons to speed up evaporation. Credit: Blake McCord, courtesy of Grand Canyon Trust

When water pumped out of the mineshaft at the Canyon Mine south of Grand Canyon National Park threatened to overflow the onsite containment pond, the uranium mine’s operator began misting the water into the air with water cannons to speed up evaporation. Credit: Blake McCord, courtesy of Grand Canyon Trust

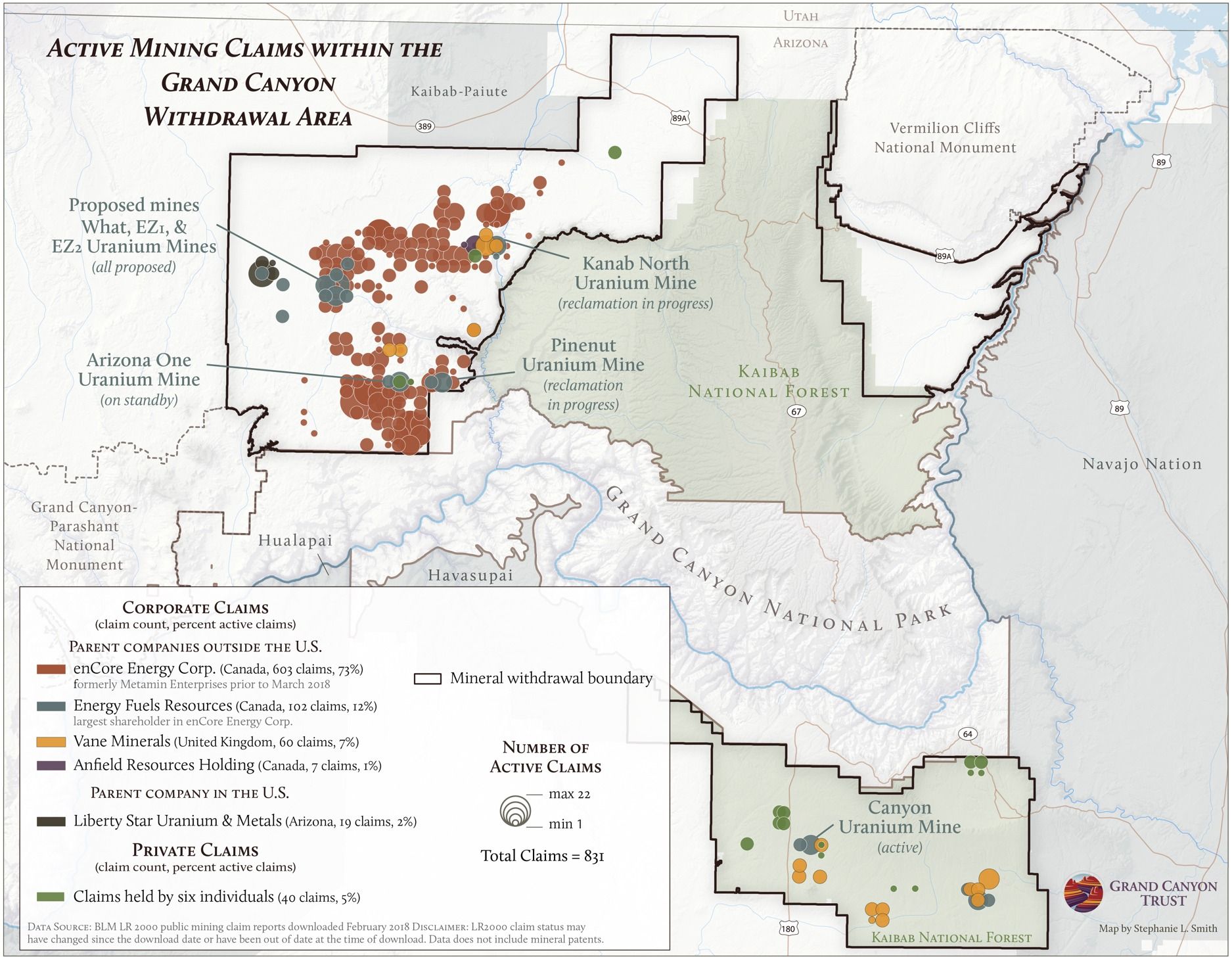

The Grand Canyon Centennial Protection Act, which passed the House today by a vote of 236–185, would permanently withdraw more than 1 million acres of public lands surrounding the Grand Canyon from new mining claims. The land withdrawal would effectively limit uranium mining in the region to a single mine that was permitted in the 1980s and has been inundated with groundwater but has not yet produced any uranium ore.

The House bill is merely the latest salvo in a long-running battle over uranium in the region. The White House raised the stakes by declaring uranium a “critical mineral” and seeking ways to stimulate US uranium mining.

“Critical mineral” listing. Proponents of expanded uranium mining got some help from the White House in December 2017, when President Trump issued an executive order intended to prevent the United States from becoming dependent on foreign sources for “critical minerals.” Among other things, the president ordered the Interior Secretary to consult with the heads of other departments and publish a list of critical minerals, defined as “a non-fuel mineral or mineral material essential to the economic and national security of the United States.”

The final list—published on May 18, 2018—identified uranium as one of 35 critical minerals. That was surprising, because uranium had never before been considered a critical mineral. In fact, a US Geological Survey list of critical minerals published only one day before the president’s executive order did not include uranium. Also, while the uranium used in nuclear weapons fits the definition of a “non-fuel” mineral, that is not the case for the uranium used in civilian nuclear reactors to generate electricity.

Access vs. protection. As part of the White House effort to reduce US dependence on uranium imports, the Commerce Department used the new critical minerals list to design a federal strategy, published in June, that would increase access to uranium and other mineral resources on federal lands. One way the federal government might do that is by changing land-use designations that restrict access to mineral resources in places like national parks and wilderness areas.

At the moment, the federal lands near Grand Canyon National Park are protected by a 20-year administrative mining ban adopted in 2012. The Grand Canyon Centennial Protection Act, if it passes the Senate and becomes law, would make that protection permanent. However, there is not yet a Senate companion bill to the newly passed House bill, and it’s likely that such a bill would face opposition from mining interests.

Waiting for the working group. In addition to the new federal strategy that made uranium a critical mineral, the Trump administration created a cabinet-level Nuclear Fuel Working Group in July and tasked it with finding ways to boost uranium mining and the US nuclear energy industry in general. The group was supposed to report to the president by October 10 but was granted a 30-day extension, perhaps because one of its co-chairs—former National Security Advisor John Bolton—no longer works for Trump.

Whatever the working group comes up with, it will be a solution in search of a problem. The United States has a huge stockpile of highly enriched uranium that can meet the nation’s defense needs for decades to come. There is no crisis on the civilian side, either. Uranium fuel for nuclear reactors is readily available from friendly countries such as Canada and Australia, and is more affordable than the lower-grade, harder-to-access uranium mined in the United States.

“Commercial uranium markets have worked well for decades,” says Steve Fetter, associate provost, dean of the graduate school, and professor of public policy at the University of Maryland, and also a member of the Bulletin’s Science and Security Board. “When expected demand exceeds supply, prices rise. But these price spikes have been temporary, because they stimulate additional production from abundant uranium resources. And price increases have little impact because uranium accounts for only a few percent of the cost of nuclear electricity.”

With no demonstrated need to subsidize uranium mining for security reasons, and a free-market system that provides sufficient uranium for civilian nuclear reactors, the administration’s efforts to boost uranium production look like a handout to the mining industry.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Grand Canyon, uranium mining

Topics: Nuclear Energy, Nuclear Risk, Nuclear Weapons