Kids are drawing pictures of the new coronavirus. That’s a good thing.

By Thomas Gaulkin, March 26, 2020

For millions of families, it may already feel like they’ve been trapped at home for years. The prospect of many more weeks, and quite possibly months, of social distancing to thwart the spread of coronavirus boggles the mind, like a kid’s idea of infinity plus infinity.

Now try being one of the more than 300 million kids living through this.

#coronavirus from the eyes of a 4 year old in northern Italy (my college friend lives there now- her daughter drew these yesterday). #stayhome #FlattenTheCurve #WeAreATeam #covid19 #MedTwitter pic.twitter.com/UZ17b1tiGZ

— Nancy H. Stewart, DO, MS (she/her) (@nvhstewart) March 17, 2020

Much of the health concern around the coronavirus pandemic has rightly focused on the populations for whom recovery is most uncertain and difficult. The elderly appear to be most vulnerable to its worst effects—adults older than 65 represent 80 percent of the COVID-19 deaths in the United States. The virus has not generally posed as great a risk to otherwise healthy children.

But children are vulnerable in other ways. With schools in dozens of countries closed down and strict social distancing measures in effect, some 50+ million children in the United States, and 300 million worldwide, are living in a whole new reality, and trying to comprehend it.

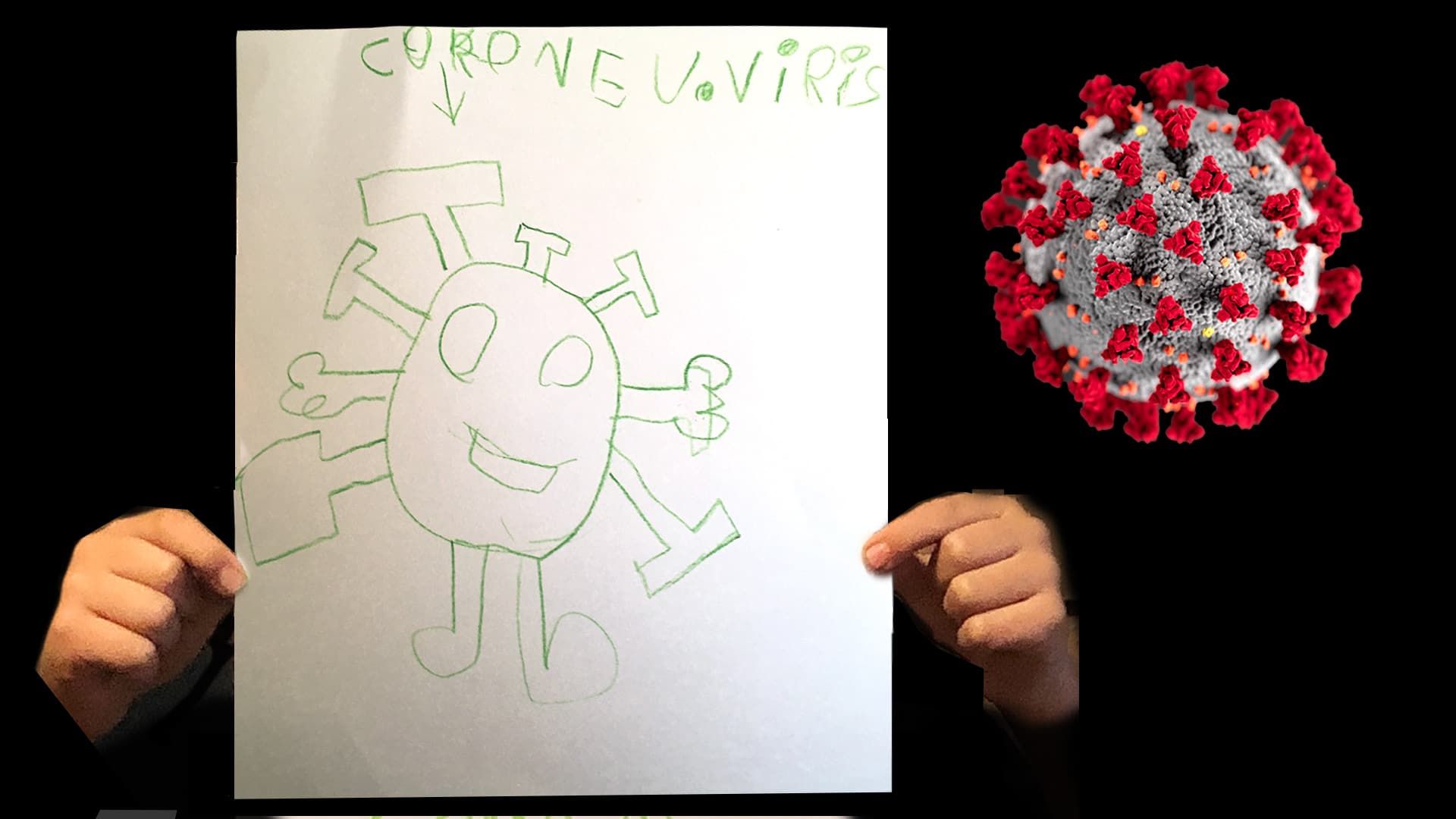

One concrete reflection of that can be seen in something young people do all the time: draw pictures. Thanks to social media—simultaneously a cesspool of misinformation and bastion of sanity during this crisis—hundreds of illustrations by children have been posted by parents eager to share. Some depict the virus as a looming presence outside, with families safe (or trapped?) inside. Others pit the virus as an invading army against an armed response. Many place a smile on the virus, perhaps to make it seem less menacing.

Experts who work on mitigating the negative impact of disasters on youth emphasize that art and other creative outlets play an important role in helping children process what’s going on around them, and offer an important opportunity for parents to help them navigate potentially traumatic events.

“If you think about children as meaning makers, they're constantly trying to make meaning of this,” University of California, San Francisco psychologist Chandra Ghosh Ippen told the Bulletin. “And one of the things that they make meaning of is danger. How much danger am I in? What does this mean for me? What does this mean for our family?”

The effects of this disaster on children have barely begun to be assessed—the scale of the crisis and the limits lockdowns impose on field research will make understanding the psychological and emotional toll on communities particularly challenging. But people who have studied and worked with children affected by previous disasters say some things are predictable: Families and communities in already vulnerable situations will struggle more. And managing anxiety will become more difficult as adults and children alike struggle the effects of social isolation and near-constant exposure to media reporting about the disaster.

Robin S. Cox is professor of the disaster and emergency management graduate program at Royal Roads University in Victoria, Canada and leads the ResiliencebyDesign Research Innovation Lab, which uses arts and other creative methods to engage young people on the problems caused by disasters, climate change, and conflict. She explained that drawing can help children express emotions they may not even know they have. “Children may not have as much access to physical activity, which is another way of managing anxiety and fear,” Cox said. “So [art] provides another way of managing anxiety and engaging with those emotions.”

Drawing also helps kids make sense of a threat that is inherently difficult to grasp, even for adults, by giving it a physical form.

Ghosh Ippen is the associate director of the child trauma research program at the University of California, San Francisco and a member of the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. She’s also authored several picture books for children on coping with trauma. “In drawings, you can do things that in life you can't do,” she said. “You can have the coronavirus be a thing. When you personify something, when you give something a body, you're able to talk about it, you're able to manage it. In play, kids are able to beat it up, they're able to jail it, they're able to yell at it, they're able to say, ‘Hey, you go away!’”

Illustrations by children have long served as a heart-wrenching reminder of the horrors experienced during and after catastrophes. The Austrian artist Friedl Dicker-Brandeis famously helped distract children brought to the Nazi’s Theresienstadt ghetto in Czechsolovakia with clandestine art lessons that have since been considered an early form of art therapy. Drawings by young students who survived the nuclear attack on Hiroshima were presented in the 2013 documentary Pictures from a Hiroshima Schoolyard. Pictures created by Syrian children in UNICEF-supported schools are both hopeful and haunting.

Sociologists Lori Peek and Alice Fothergill spent seven years studying children who were directly affected by Hurricane Katrina, which displaced more than a million people from the Gulf Coast in 2005. Although the experience of affluent families was often very different than what lower-income communities saw, Peek said that she and Fothergill noticed that many children displaced by the hurricane reflected on it in similar ways.

“The kids were all drawing these pictures that always had black or brown crayons to color this dark, murky water,” said Peek, professor of sociology and director of the Natural Hazards Center at the University of Colorado, Boulder. “And sometimes it was kids who'd been in the water, who'd really seen the water. Sometimes it was kids who hadn't seen it, but they knew about it through the media, or just through stories. But there was this remarkable consistency in what children were coloring.”

Peek believes that children’s responses to the current pandemic are likely comparable to past “slow-motion” disasters. “There are definitely parallels,” she said. “I think some of the creative interventions that children may be drawing in the context of climate change, or in the context of Katrina—where the emergency period lasted for a long period of time—might have certain parallels to what you're seeing with COVID.”

Cox, who has developed multiple “psychosocial planning” documents for the Canadian government’s disaster preparedness programs, said that attention to the psychological impacts frequently takes a back seat to infrastructure and economic recovery. But the 2003 SARS and 2009 H1N1 epidemics served as a wake-up call. “It became very clear that not only were there huge psychological and emotional costs for healthcare workers and other people impacted, but also that those costs were exponential in terms of the ripple effect across communities and economies,” she said.

Advice now abounds online for the billions of people grappling with how to keep their families both physically and emotionally healthy while becoming experts at social distancing. One of the simplest things parents of younger children can do is just to spend some time in a dialogue with them through expressive activities their kids enjoy.

“I would encourage grownups to … just be present, be at the table,” Ghosh Ippen said. “Some kids like to draw, other kids like to do other things. They like to do it with Play-Doh, you know, finger paints—it is both an activity that you're doing together and a chance to share your reality together.”

The disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic will cause all kinds of predictable and unpredictable harm and hardship. But Peek notes that the time spent at home is also an opportunity—not always available during natural disasters like tornadoes, wildfires, and hurricanes—to come up with valuable interventions while the disaster is still unfolding.

“If there's any lesson from disaster research … that’s important right now, it’s that saying nothing is not the right thing to say,” Peek said. “This is a moment to really process this in real-time, and to invite children in, and to open up the opportunities for them to share in ways that are age-appropriate.

“Children are a quarter of our population, but they're 100 percent of our future, and so, you know, we have to pay attention to them.”

Here is another thank you card from a child. I love the picture - it is in the shape of #Covid_19 with the spikes representing words like “awesome” and “amazing”, medical stuff including bandaids, stethoscope and syringes and of course a #teddybear pic.twitter.com/qMvHkGg8AB

— Mark B. Pochapin, MD (@MarkPochapin) March 20, 2020

Keywords: Coronavirus, art, children, mental health, social media

Topics: Biosecurity, Multimedia

Share: [addthis tool="addthis_inline_share_toolbox"]