Breaking gender barriers: Ruth Bader Ginsburg and … Marie Skłodowska Curie

By Sara Z. Kutchesfahani | September 30, 2020

The US Supreme Court building. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

The US Supreme Court building. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

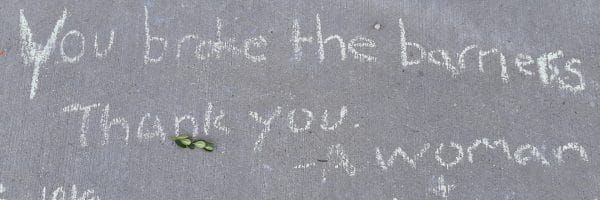

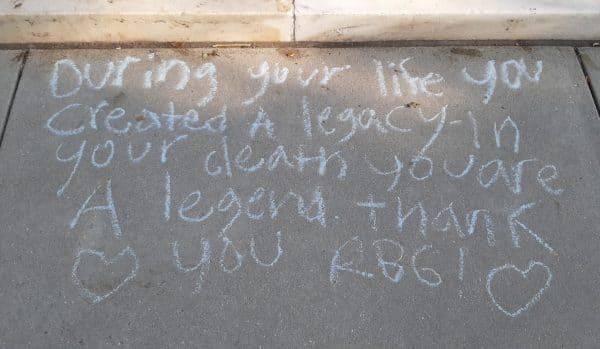

On September 18, as people across the United States were finishing up the work week, they were confronted with the horrible news of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death. A mere 12 hours later, while on my morning constitutional, which happens to pass by the Supreme Court, I noticed all the wonderful tributes scribbled on the sidewalks leading up to the monumental flight of broad steps and the portico of tall Corinthian columns. As I stopped to read each and every touching message, I couldn’t help but ask myself, “Who might the RGB of the nuclear field be?” I confess, I grappled with the question for a day, until it suddenly came to me. Marie Skłodowska Curie.

Both were trailblazers in their respective fields. Justice Ginsburg fought against gender discrimination and for the rights of women, and notably took pre-existing discriminatory laws and eviscerated them one by one. Curie was a renowned physicist and chemist who conducted pioneering research on radioactivity—a term that she herself coined. Her efforts with her husband Pierre led to the discovery of polonium and radium, and she championed the development and use of X-ray equipment. In fact, the science that Curie introduced to the world inevitably led to her death. She died from exposure to radiation in the course of her scientific research and her radiological work at field hospitals during World War One. The Curie Institutes in Paris and in Warsaw remain major centers of medical research today.

The lives of Justice Ginsburg and Curie did not intersect: Ginsburg was a year old when Curie died. But the similarities in their groundbreaking paths in challenging the dominant male hierarchies in their chosen fields of science and the law are noteworthy. Ginsburg will forever be remembered as a champion of race and gender equality and as a pioneering lawyer on women’s equality—not to mention the second woman to serve on the US Supreme Court. Curie, meanwhile, was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, the first person and only woman to win the Nobel Prize twice, and the only person to win the Nobel Prize in two scientific fields: physics and chemistry. She was also the first woman to become a professor at the University of Paris. Yet, in spite of their accomplishments in shattering the proverbial glass ceiling, their respective fields have yet to approach anything like gender parity. To be blunt, the number of Curies in nuclear science, let alone nuclear policy, is not dissimilar to the number of Ginsburgs in the upper echelons of the legal profession.

A 2019 New America report about women in nuclear security observed that the public image of national security professionals continues to remain highly masculinized, with a dramatic underrepresentation of female professionals. Even the jargon used in the nuclear security field is highly sexualized. In her seminal 1987 piece “Sex and Death in the Rational World of Defense Intellectuals,” Carol Cohn observed:

Lectures were filled with discussion of vertical erector launchers, thrust-to-weight ratios, soft lay downs, deep penetration, and the comparative advantages of protracted versus spasm attacks—what one military adviser to the National Security Council has called “releasing 70 to 80 percent of our megatonnage in one orgasmic whump.”

The field even has a gendered nickname for the small exclusive group of male nuclear experts and leaders: the nuclear priesthood.

Moreover, on the international level, there has been a poor record of women’s representation in multilateral forums dealing with arms control, nonproliferation, and disarmament. In 2000, the United Nations Security Council passed the first landmark resolution on women, peace, and security, Resolution 1325. It addresses the impact of war on women and the importance of women’s full and equal participation in conflict resolution, peacebuilding, peacekeeping, humanitarian response, and post-conflict reconstruction. Yet 20 years later, women diplomats are still significantly underrepresented in multilateral fora dealing with these issues. For example, while the proportion of women participating in arms control, non-proliferation, and disarmament-related meetings has grown steadily over the last four decades, women still remain underrepresented. In meetings of over 100 representatives, women comprised just 32 percent of the participants; in smaller forums the average proportion of women dropped to 20 percent.

These statistics are striking, especially when there are talented women in the nuclear security field. For example, the last two nuclear agreements joined by the United States were negotiated by women: Rose Gottemoeller (former deputy secretary general of NATO and former US under secretary of state for arms control and international security affairs), who negotiated the New START Treaty; and Ambassador Wendy Sherman (former US under secretary of state for political affairs), who negotiated the Iran nuclear deal. Another woman, Ambassador Laura Holgate, ran an unprecedented international effort to reduce the threat of nuclear terrorism. Another woman, Jill Hruby, ran one of the country’s three nuclear weapons laboratories. And yet another woman, Beatrice Fihn, leads a campaign that won a Nobel Peace Prize for its efforts to abolish nuclear weapons.

Like Curie before her, Justice Ginsburg inspires many more than just those who would join her own profession. Even though the nuclear policy community is still far from reaching gender parity, her legacy serves as a reminder that at the heart of gender equality is the recognition that women, as well as men, have the capability break new ground and the right to an equal voice.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Ruth Bader Ginsburg, US nuclear policy, gender gap

Topics: Columnists, Nuclear Risk

We thank Dr. Kutchesfahani for this excellent article. The IAEA has just started The Marie Sklodowska-Curie Fellowship Programme (MSCFP). The MSCFP aims to help grow the number of women in the nuclear field, supporting an inclusive workforce of both men and women who contribute to and drive global scientific and technological innovation. https://www.iaea.org/about/overview/gender-at-the-iaea/iaea-marie-sklodowska-curie-fellowship-programme I also want to remind the readers that Vienna produced Dr. Lise Meitner who was a key contributor to the discovery of nuclear fission. She was born in Vienna on Heinestrasse where a plaque notes her birthplace. She attended the Gymnasium that also produced Erwin Schroedinger. She… Read more »