The world just got serious about dealing with climate damage

By Taylor Dimsdale | December 12, 2022

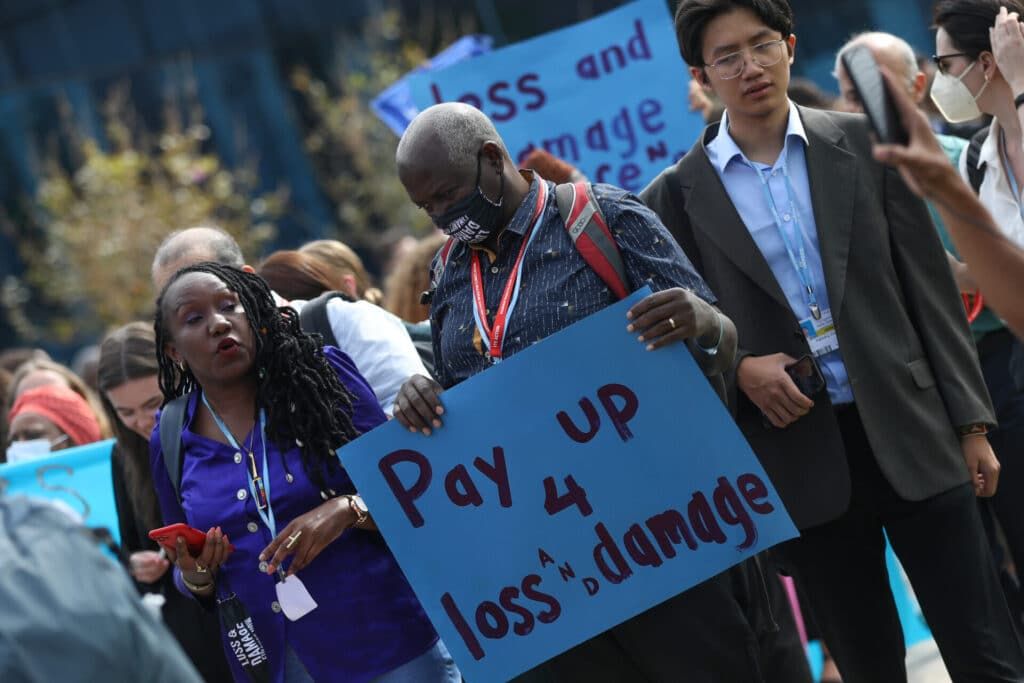

Demonstrators with signs at COP27 (UNclimatechange/Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Demonstrators with signs at COP27 (UNclimatechange/Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

If you had polled a random sample of climate experts and insiders ahead of COP27 on which issue was most likely to bring the negotiations crashing down, most would have given the same answer: the plan to raise money to address climate impacts in developing countries, otherwise known as loss and damage.

Instead, it was the crowning achievement in Sharm el-Sheikh.

After more than two weeks of fraught meetings and late nights, countries reached an agreement to establish a new fund designed to help developing countries cover the cost of climate impacts, like extreme weather events, sea level rise, and desertification. Less surprising but also important was the agreement to set up a new institution, called the Santiago Network, which will provide technical assistance to vulnerable countries. Several factors came to bear on COP27’s big success story.

First, loss and damage received newfound attention in the past two years as impacts around the world have become more frequent and more severe. Put plainly, the suffering of frontline communities and countries has become impossible to ignore. See any number of recent examples, from massive flooding in Nigeria, to a record-breaking spring heatwave in Pakistan, followed by devastating summer floods that displaced 33 million people and left one third of the country underwater.

In the run up to the summit, there was a flurry of behind-the-scenes diplomacy between a small group of developed and developing countries. Developed countries, which had been unified in their opposition to any discussion on loss and damage, started to break ranks. Before the conference, Denmark followed Scotland and Wallonia, a region in Belgium, in announcing they would earmark some development assistance for loss and damage. The United States and European Union softened their positions and allowed it to be included on the formal agenda for the first time at the start of the summit.

Once things kicked off in Sharm el-Sheikh, it quickly became clear that loss and damage would indeed be the decisive issue in the negotiations. Developing countries decided that the measure of success was the establishment of a new fund and demonstrated a remarkable degree of unity in their messaging. Several developed countries including Austria, Germany, and Ireland announced pledges for loss and damage finance. New Zealand was among the first to indicate that they were open to a new fund.

In the final hours, the United States and European Union blinked. Whereas in Glasgow it had been the developing countries accepting what they viewed as a disappointing outcome in order to keep the show on the road, in Egypt it was developed countries that ultimately relented on loss and damage finance, despite not getting much in return on their wish list, the top item of which was securing new mitigation pledges to increase the chances of meeting the 1.5-degree Celsius temperature target. While the world is off track for keeping temperature rise below that threshold, scientists say the worst-case scenarios can still be avoided. The best-case right now would be 1.8 degrees Celsius, with something like 2.6 degrees Celsius far more likely. In either case, impacts will get worse before they get better. And it will be difficult to maintain international cooperation, trade and security in a world of relentless storms, droughts, and floods. Vulnerable countries are already facing debt distress due in part to paying so much to recover from disasters, not to mention rising food and water insecurity.

The agreement on a fund was a sign of political goodwill. But even when the fund is operational, the resources that individual countries can contribute will pale in comparison to the cost of climate impacts in developing countries. That’s why there was something equally important baked into the decision texts in Egypt: a serious discussion about how to reform the global financial architecture in a way that dramatically expands the pool of resources and finance for addressing climate change.

Multilateral and international financial institutions like the World Bank and International Monetary Fund have been asked to consider how they could fast-track and scale up finance for loss and damage, and the cover decision calls for multilateral development bank reform to make them “fit for adequately addressing the global climate emergency.” International financial institutions are to report back at the spring meetings in April 2023.

This breakthrough was the result of a few factors, including lobbying from the United States to better deploy multilateral development banks, as well as the Bridgetown Initiative, a set of proposals put forward by Prime Minister Mia Mottley of Barbados and supported by President Macron of France that would, among other things, significantly increase the amount of finance available for climate action and provide debt relief to vulnerable countries facing climate disasters. The agreement in Sharm el-Sheikh was closer to the end of the beginning of efforts to address climate risk than to the beginning of the end. The hard work now begins, and many questions remain to be answered. A Transitional Committee, made up of 24 country representatives, has been tasked with figuring out the details, including where the money will come from, who will pay it, and who will receive it. The committee will report back with recommendations in a year, at COP28 in Dubai. In the context of climate negotiations, that’s the blink of an eye.

What is clear however is that for the first time a serious, global discussion has been launched on how to establish a new international framework on climate resilience. The level of mitigation needed to ensure a safe climate won’t be possible without better climate risk management. Now, there’s a fighting chance.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: COP27, climate change, climate crisis, climate talks, global climate talks, loss and damage

Topics: Climate Change

A timely article, along with one just out from Reuters: how India is contracting with Airbus and Boeing for 500 JETLINERS! How convenient it is , to demand climate damage reparations from the large energy consumers of the world….and then go ahead and demand money so you can become one of them!!! so much for COP27. The poorer nations demand guilt money….but refuse accountability for their own development plans that will violate all the things COP 27 was supposed to stop. Hypocrisy anyone?

I am sure that accountability mechanisms are included, history shows that the developed really don’t just throw away money to developing countries without strings attached. The United States, for example, throws away 1 trillion a year on its military-industrial complex, which emits more carbon than all but the most wealthy countries…which pales in comparison to India’s 500 jetliners. We could carry on with finger-pointing contests all day. The fact is, us in developed countries (which includes China) have the most cumulative emissions. We are most responsible. Our fates are bound to poorer countries. We rely on them for natural resources… Read more »