Partnerships, not parachutes: How Indigenous knowledge and citizen science can enhance climate research

By Chad Small | August 21, 2023

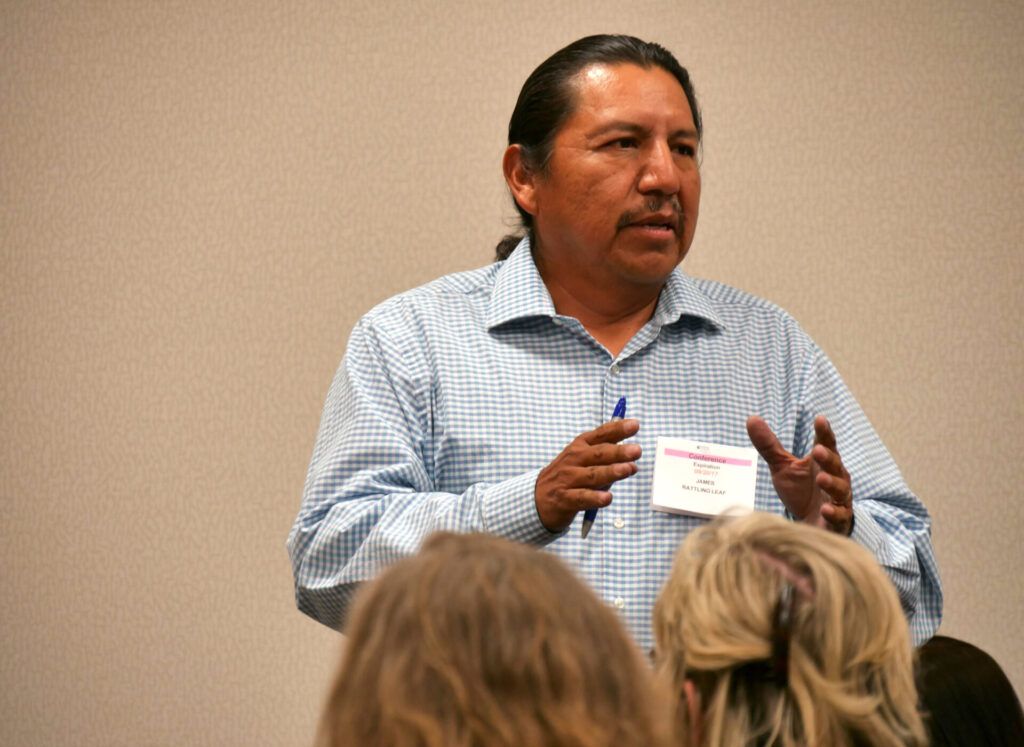

An Ashéninka leader from Peru discusses satellite maps of the Upper Amazon. Geographers with SERVIR, a joint program of NASA and the US Agency for International Development, heard feedback on their data as part of an effort to “center the expertise and experience of Indigenous communities in Earth science research.” (Photo: Reynaldo Vela / USAID)

An Ashéninka leader from Peru discusses satellite maps of the Upper Amazon. Geographers with SERVIR, a joint program of NASA and the US Agency for International Development, heard feedback on their data as part of an effort to “center the expertise and experience of Indigenous communities in Earth science research.” (Photo: Reynaldo Vela / USAID)

Climate data has a completeness problem. If you’re looking for ancient carbon dioxide measurements, ice core data can give you that. If you have an interest in prehistoric ecology, the fossil record is your best resource. The problem, however, is that often climate information is either globally averaged, or not distributed evenly throughout the available data record. This creates data gaps.

In the modern era, satellites provide information on surface temperature, vegetation dryness or composition, and even marine biodiversity. Still, satellite records only go back about 50 years, and even better spatial coverage doesn’t ensure good enough resolution of that data. Ultimately, that means that there are tools missing from the environmental and climate science toolbox. But there are alternative solutions, if the broader scientific community will accept them.

Increasingly, researchers have argued that knowledge from Indigenous communities can aid the Western scientific tradition in meeting the world’s crises. Because Indigenous communities existed on their lands long before colonization, their observations can fill in gaps that modern data gathering tools cannot.

Over the past decade, there has also been a push to expand observational toolkits to improve research. Citizen science has allowed regular people—often those in frontline communities—to become information seekers and testers. This work has proved useful because satellites often can’t beat boots-on-the-ground when it comes to hyperlocal data gathering. These projects—like those that incorporate Indigenous knowledge—are special because they involve people often excluded from the scientific process altogether. Despite challenges in adoption and implementation, projects using Indigenous knowledge and community science to enhance environmental science research have improved outcomes in spaces from Arctic agriculture to urban public health.

One of the biggest schisms between Western science and Indigenous knowledge is the nature of how conclusions and observations are made. Vivek Shandas, founder and director of the Sustaining Urban Places Research Lab at Portland State University, describes much of Western science’s data collection and research paradigm as “measure it and then it has meaning.” Indigenous knowledge, on the other hand, often comes from a culturally informed, and purely observational place.

To get around this potential incompatibility, James Rattling Leaf, Sr., member of South Dakota’s Rosebud Sioux tribe has advocated for a third mode, called ethical space.

Ethical space can be compared to the coaching staff on a football team. Scientists and Indigenous knowledge holders act as the defensive and offensive coordinators, respectively. Each coordinator comes with different skills and different strategies that help the team. Additionally, neither coordinator questions the legitimacy of their counterpart’s plan, validates each other’s methods, or modifies each other’s strategies. This allows both plans to be equally instrumental in the team’s overall success. In this way, ethical space leaves the core values of Western science and indigenous knowledge intact while providing room for them to mutually share their most useful problem-solving assets.

“As Indigenous people we don’t say we don’t like science; we do use it [too], but we also understand that we also bring our knowledge too,” Rattling Leaf says.

Rattling Leaf adds that it’s possible to “consider [and] learn the principles and protocols of the two ways of knowing.” According to Rattling Leaf, ethical space is the venue in which larger existential battles like climate change can be fought. He notes that an ethical space framework allowed cultural burning practices to finally be considered a more serious wildfire mitigation strategy.

Rattling Leaf puts this framework into practice as a tribal engagement specialist for the North Central Climate Adaptation Science Center. The regional Climate Adaptation Science Centers managed by the US Geological Survey are an example of a scientific enterprise formally making space for Indigenous knowledge. The centers fund research projects that generate data sets and tools to help natural and cultural resource managers respond to climate change. The centers work with tribal nations to ensure that tribal leadership can act as co-primary investigators on research endeavors.

In August, the US Geological Survey finalized an agreement to add more consortium members into the Alaska, Northwest, and Southeast Climate Adaptation Science Centers, specifically more tribal organizations. This expansion “reflect[s] our continued commitment to providing accessible climate adaptation science for the landscapes and communities that need it most,” Doug Beard, the national chief of the Climate Adaptation Science Centers, said in a press release.

Ethical space can also create “cultural safety” and “psychological safety” for Indigenous partners in scientific research. PolArctic, an oceanographic and data science company providing business and policy advising throughout the Arctic, has used it to maintain cultural and psychological safety for its Indigenous clients in Alaska. As Leslie Canavera, CEO of PolArctic, explains, even when Western scientists see the value in Indigenous knowledge, they often behave like “parachute researchers” who create purely extractive relationships with tribal partners. Parachute researchers use Indigenous knowledge without care to how it’s applied, collected, or whether the subsequent research benefits the tribal nations at all. This is where Canavera’s work with PolArctic is unique.

“One of the good things also is that we’re a business, and we’re not researchers,” she says. “Researchers publish all their data, and communities want to be able to control their own information and data.”

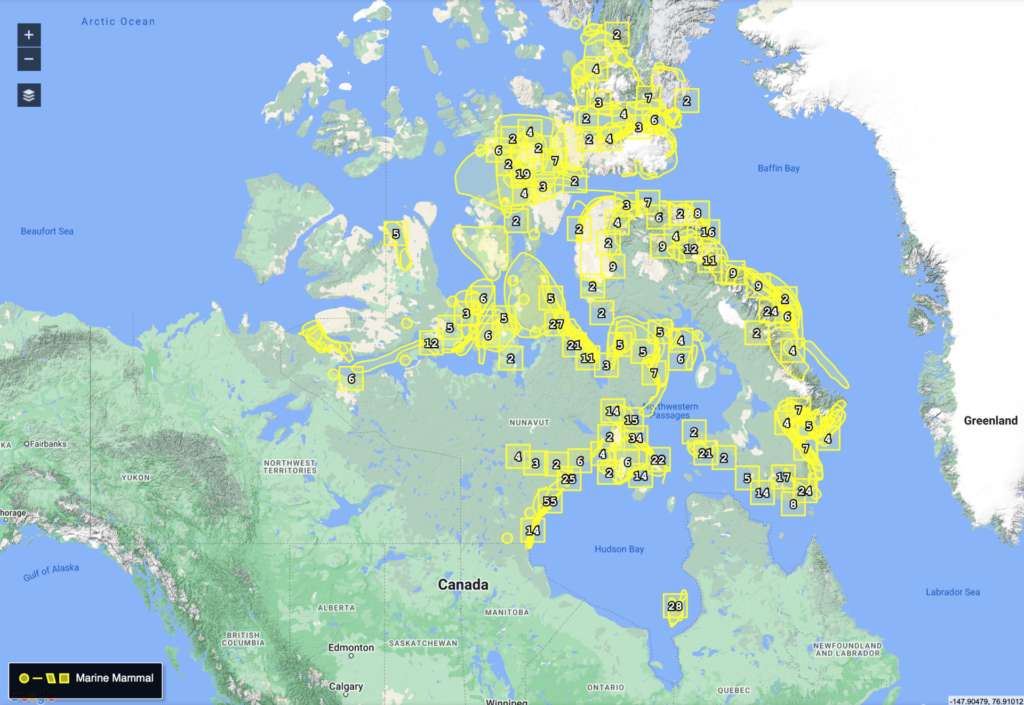

The proprietary nature of PolArctic’s work means that it’s better able to protect generational knowledge important to these communities. In doing so, PolArctic is also able to disrupt the Arctic “data desert.” PolArctic uses remote sensing data from satellites to provide advice to its clients throughout the Arctic. Remote sensing data doesn’t capture everything, and in situ observations in the Arctic are difficult due to the extreme weather conditions. PolArctic used Indigenous knowledge to work around these issues.

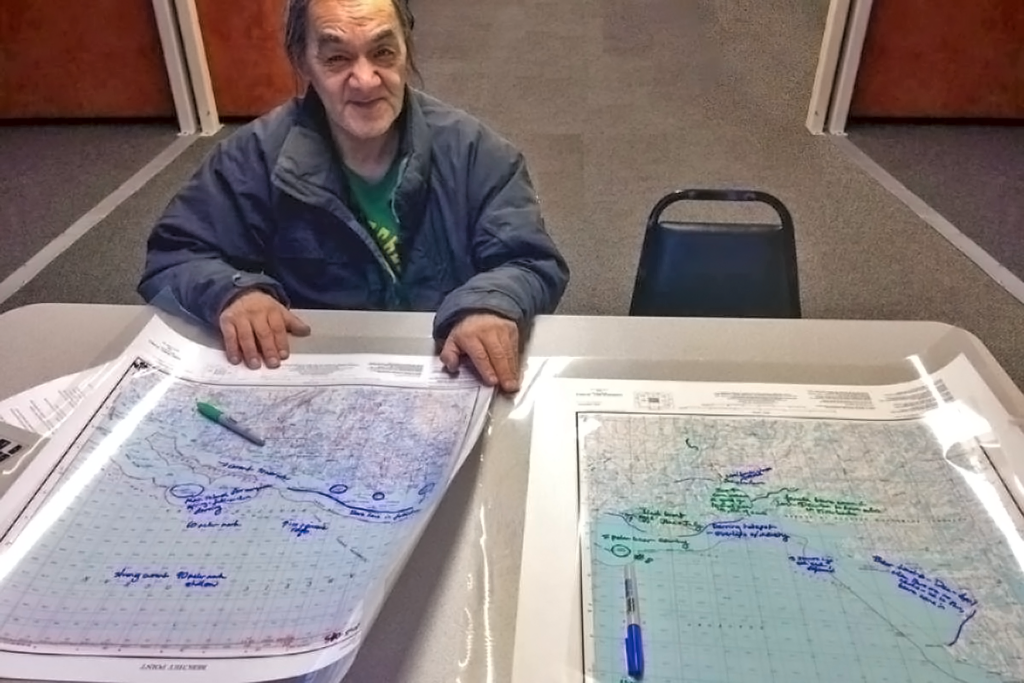

“The Canadian government had a resource called the Nunavut Coastal Resource Inventory,” Canavera explains. “[In it] they had gone to a bunch of elders and community members and said ‘Where do you find polar bears? Where you find seals?’, and they drew [that] on the maps.”

PolArctic digitized these maps, and along with remote sensing data, used this information to train artificial intelligence models to locate different species in the Arctic. The value add for the Inuit community was immediate and immense. It gave them marine farming data in detail—and in the local language—that they didn’t have before.

From a technical standpoint, Canavera sees what PolArctic did as a proof of concept for how artificial intelligence and Indigenous knowledge can fit hand-in-glove to improve research. Because Indigenous knowledge is more of a static data output (it’s not a variable that’s changing rapidly) it works better in artificial intelligence models than some physics-based weather and climate models where outputs change as conditions change. Beyond that, artificial intelligence could incubate projects that incorporate more types of climate data coming out of Indigenous knowledge spaces.

“How [ice and snow] smells actually changes based on different temperatures,” Canavera explains. “That’s been a lot of the conversation in communities about how the smell is changing, the sound is changing, but western science has no room for those kinds of observations.”

Without ethical space as an intellectual meeting-ground, these benefits to the community and the technological advancements would not be possible.

“Ethical space welcomes Indigenous elders as valid holders of important information as well as a PhD person,” Rattling Leaf says. “We don’t see one as greater than the other.”

Treating Western science tools and Indigenous knowledge holders as equal contributors allowed PolArctic to root the science research and deliverables in the lived experience of the Inuit community. This line of thinking has also inspired contemporary community science endeavors.

During the 2021 Pacific Northwest Heat Dome, Vivek Shandas was working on an unprecedented project to map out the urban heat island effect in Portland. Shandas led a team that trained community members throughout Portland to take temperature measurements throughout the city to get incredibly high-resolution information about heat risk inequities. This work has both physical science and public health ramifications. For Shandas, however, it also comes from a place of wanting the physical sciences to “be a bit more grounded in the lived realities of places.”

Like the ethical space work done using Indigenous knowledge to build lasting and trusting partnerships, Shandas says that the communities he works with do more than just take measurements.

“The community groups help identify where to collect the data and what kinds of data to collect,” he says.

These measurements often include common meteorological variables like temperature, humidity, and wind speed. The measurement process itself allows the project to give right back to the community itself.

“We use those instruments to then lead into a conversation about what these measurements mean and what would give them meaning to local communities,” Shandas explains.

When discussing an issue like the urban heat island effect, giving the community information about where heat risk is higher (and potentially why it’s higher) allows stakeholders to both mitigate risks and advocate for policy solutions. Additionally, Vivek mentions that it creates a real-time teaching lab for people of all ages, and of all science interest levels.

Across the country, Drew Gentner, associate professor of chemical and environmental engineering at Yale University, worked on a community science project that investigated air quality in Baltimore. Community members and organizations were given air sensors to distribute throughout the city to determine how regional and local influences affect air quality. As Gentner explains, this work requires a lot of buy-in from community members to sample as many diverse locations within the city as possible. The output data from this project was then distributed to schools. Beyond just using this as a moment to just teach students about science, it also provides the community with deeper information about their health risks.

Baltimore once had the highest air pollution mortality rate of any major city in America. While the air quality has improved over the last two decades, the city still experiences dangerous air quality days with troubling frequency. Many sources, from traffic emissions on Baltimore’s numerous highways to combustion sites like the Wheelabrator trash incinerator contribute to Baltimore’s poor air quality. For residents and activists, the monitoring system provides safety information where agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency fall short.

“Environmental Protection Agency hasn’t updated our federal air quality standards in years, and many organizations say they’re not protective enough of human health,” Morgan Folger, a clean car campaign director for Environment America, told Inside Climate News.

This makes the data provided by this project more meaningful beyond just the technical outcomes.

“We’re sharing that data back with those community partners so that they can get a sense for what the data they helped collect looks like, what their local levels are, and how that compares to the overall regional averages,” Gentner explains.

While Indigenous knowledge and community science both have clear benefits to the communities they depend on and the scientific community, they still face pushback. The community science space, despite using the tools and practices of Western science, has its hurdles. Shandas points out that this work often isn’t validated by academic advancement processes like tenure review because it’s incredibly time-consuming work that may not lead to numerous publications.

Indigenous knowledge advocates often have to prove that their contributions are credible. Rattling Leaf says there are some scientists who see Indigenous knowledge as folklore that wouldn’t survive peer review. Canavera contends that the peer review here is generations of communities who have survived using this knowledge.

“We’ve had thousands of years of peer review; that’s what this data is,” she says. “If it was wrong, you died.”

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: citizen science, climate crisis, climate science, data, indigenous science

Topics: Climate Change