How is climate change impacting hurricane season? It’s complicated

By Jessica McKenzie | September 7, 2023

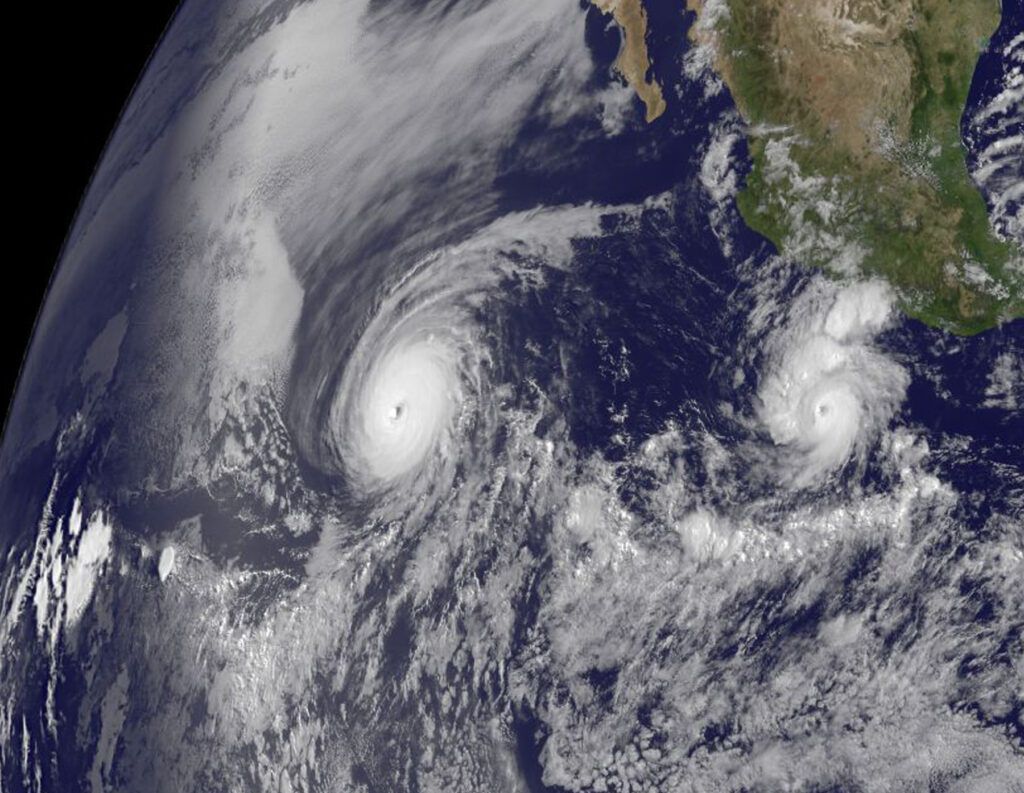

This satellite imagery from June 25, 2010, shows the powerful Hurricane Celia (left) with the larger eye, and behind it Hurricane Darby (right) with a much smaller eye. (NASA)

This satellite imagery from June 25, 2010, shows the powerful Hurricane Celia (left) with the larger eye, and behind it Hurricane Darby (right) with a much smaller eye. (NASA)

In mid-August, a hurricane developed over the Pacific Ocean and made landfall in Mexico as Tropical Storm Hilary, eventually swamping parts of Southern California with heavy rain. Later that month, Hurricane Idalia ripped through the Big Bend region of Florida. Even though the storm passed through a rural area, with nowhere near as much damage or loss of life as last year’s Hurricane Ian, it is estimated that privately insured losses could reach $5 billion.

Another storm, Hurricane Lee, is currently building strength over the Atlantic Ocean, and is expected to become a Category 4 hurricane with sustained wind speeds of 150 mph before the weekend, although forecasters don’t currently think the storm will blow towards the United States. Experts now estimate the Atlantic hurricane season will produce between 14 and 21 named tropical cyclones this year, slightly more than predicted earlier this year (between 12 and 17).

Is climate change impacting the frequency and intensity of hurricanes? Do El Niño or the extraordinarily warm sea surface temperatures recorded around Florida this year make hurricanes more likely or powerful?

The answers to those questions are, in short, complicated. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists reached out to Thomas R. Knutson, a senior scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration who studies tropical cyclones, to respond to these and other questions about climate and hurricanes with an appropriate level of nuance.

The following interview has been condensed and lightly edited.

Jessica McKenzie

What’s the difference between attributing specific storms to climate change versus looking at trends over time?

Thomas Knutson

Event attribution is where we’re trying to say how the likelihood of some type of event has changed due to anthropogenic forcing. In some cases, we can say the event would very likely not have happened without anthropogenic forcing, for example, the case of the 2016 global temperature record.

Trends are somewhat more straightforward. For example, with global mean temperature, this data set has a very strong rising trend, and we can use models and other methods to try to assess how likely is such a trend just due to natural variability.

To go from an 1860-type climate to the point where you had that new record in 2016, you really require anthropogenic forcing, at least according to climate models. So that’s a case where we can go all the way and say basically the event appeared to be impossible without the addition of anthropogenic climate change.

In other cases, you can say anthropogenic climate change made this event two to six times more likely, or something like that. It’s talking about the probability of occurrence. The purpose is to try to estimate the relative role of anthropogenic climate change versus other factors in causing a certain type of event.

McKenzie

What evidence is there that climate change has already influenced or impacted hurricane activity on a broader scale?

Knutson

That’s a good question. The fraction of the overall number of hurricanes which are Category 3 or higher has been increasing since the late 1970s. And the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has stated that there’s medium confidence now that this change is outside of natural variability.

Notice they aren’t fully attributing it to anthropogenic forcing. There are different steps you go through to reach different levels of attribution. For example, IPCC does attribute global mean temperature increase, largely to have been due to anthropogenic forcing, of course, but they’re not really attributing observed hurricane changes at this point to anthropogenic forcing.

Models suggest that with anthropogenic warming, you’re going to have more extreme rainfall rates out of hurricanes, but we haven’t yet identified that signal clearly in observational data. Whereas the IPCC and other review studies have identified such a signal in observed extreme precipitation in general, just not for hurricanes.

McKenzie

What are the specific challenges of looking at hurricanes and attributing changes to either anthropogenic climate change or to natural variation?

Knutson

I think one reason it’s such a challenge is because there’s low signal to noise. In the case of global mean temperature, you’ve got a really strong signal emerging in the observational data where you can just look at the time series and see that very systematic rise over time, decade over decade.

Now, shifting gears away from global mean temperature to Atlantic hurricanes: One of the relatively long and reliable records that we have is the counts of hurricanes making landfall in the United States. It could be major hurricanes or tropical storms, or all hurricanes. But these time series are not showing any significant trend over time. So that’s telling us that there’s apparently not a very strong impact of greenhouse warming on the frequency of hurricanes making landfall in the United States, because we have more than a century—120 years—of decent data on that and it’s not really showing a trend. So again, it gets back to this low signal to noise issue.

Another huge problem is the presence of strong multi-decadal variations of different hurricane indices in the Atlantic basin. So if you look at something like major hurricane counts in the Atlantic basin, that had a relatively high period in the 1950s and 60s, followed by a few decades where it was relatively low, in the 1970s and 80s. Sometimes this latter time period is referred to as a major hurricane drought. And then since 1995, it’s been relatively high again. So it’s been going back and forth: high then low then high.

Now, sea surface temperatures in the tropical Atlantic also were sort of high then low then high, but also superimposed on the sea surface temperatures is a rising trend. So, in the main development region, sea surface temperatures have been fluctuating on multi-decadal timescales, but with a rising trend.

The problem we’re having here is that the multi-decadal fluctuations make it harder to identify trends in various metrics in the Atlantic basin. And if you just look at part of one of these multi-decadal cycles, so if you start around 1980 and go forward from there, then you tend to see a rising trend in all kinds of metrics in the Atlantic basin: numbers of hurricanes, rapid intensification, numbers of major hurricanes, and so forth. But those trends, since 1980, are probably not representative of century-scale trends.

McKenzie

What do you mean, they’re not representative of century-scale trends?

Knutson

Well, if you look at the record that we have of basin-wide hurricane counts in the Atlantic basin—this gets a little tricky, because that one actually does have a rising trend, the raw hurricane counts. But our ability to actually observe hurricanes in the open basin has changed a lot over time. Once we put up satellites, we were able to see much more clearly what was going on in the full basin. And in the pre-satellite era, we’re almost certain that there were hurricanes out there that were never observed, that were overlooked. And so if you make some type of statistical correction for that, you basically come up with very little trend since 1900, which is consistent with the landfalling record. But it is a very crude estimate, as it was just based on some statistical assumptions.

The point is that you do have a rising trend, since 1980, but when you have a longer-term record that goes back to 1900, in those types of records, there’s very weak evidence for a century-scale rising trend.

McKenzie

Temperature, you’ve said, is a really clear example of something that’s easy to track with greenhouse gas emissions. Hurricanes are more complex; is it possible there’s a delayed reaction to global warming that could explain this slight increase starting in 1980?

Knutson

You know, it’s possible that some of this increase since 1980 is greenhouse-gas driven. But the problem is we also have some other candidate mechanisms. For example, aerosols. Aerosols are this haze that’s produced when emissions of sulfur dioxide from burning burn fossil fuels are converted into sulfate aerosol particles. So sulfate aerosols, which were in relatively high concentrations, apparently, over the Atlantic basin, up into like the 50s and 60s and 70s. But then you had the Clean Air Act.

We think that those aerosols were cooling off the Atlantic, and when you removed those aerosols, the Atlantic started to begin warming up due to that effect. So that is a way in which it’s anthropogenic, in this case, it’s reducing aerosols, and that’s leading to increases in hurricane activity. So that’s a way in which we think anthropogenic forcing, overall, may have led to at least some of that increase since 1980. But it’s not a greenhouse gas-driven effect. It’s an aerosol-driven effect.

We have another school of thought, which attributes a lot of this and perhaps all of this increase in major hurricane activity in the Atlantic since 1980 to a natural fluctuation in ocean circulation. We have this large-scale Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation in the Atlantic basin, and a number of scientists think that that’s the primary driver of these multi-decadal hurricane fluctuations in the Atlantic basin.

So the problem is that for this increase since 1980, we have a number of suspects. Until you can quantify the contributions of these different suspects, it may be premature to make a very strong attribution to one particular suspect, namely, increased greenhouse gases. And greenhouse gases may have had different types of effects on the Atlantic hurricanes. Some of the models that I’ve run show that an increase in greenhouse gases and further global warming is expected to lead to fewer hurricanes in the Atlantic basin, but the hurricanes that do happen tend to have higher average intensities, and higher rainfall rates. So it was kind of a mixed bag: Fewer storms, but stronger, and higher rainfall rates.

Of course, we haven’t mentioned sea level rise yet. But that’s another case where we have a pretty obvious trend going on globally, while also seeing that trend or different manifestations of it along the Atlantic and Gulf Coast.

McKenzie

Will that change how hurricanes behave?

Knutson

Other than the fact that higher sea level leads to greater inundation risk for a given storm, we don’t have any indication that sea-level rise is going to be a major player in the behavior of hurricanes. It’s complicated.

Concerning ocean warming, which is a contributor to sea-level rise, if the ocean warms more near the surface than at depth, that may be something which can affect hurricane behavior. But that’s a little different question from what you were asking.

McKenzie

I’m glad you brought that up. Will the extraordinarily high temperatures sea surface temperatures recorded around Florida this year impact the rest of hurricane season? Or in future years, if it continues to be that hot?

Knutson

It depends. Based on the work we’ve done to date, what seems to be really important for hurricane activity in the Atlantic basin is the amount of warming you get relative to the amount of warming that occurs elsewhere in the tropics. If the rest of the tropics warms more than the main development region in the Atlantic, that would tend to favor less activity in the Atlantic. Conversely, if the main development region in the Atlantic warms more than the rest of the tropics, that could bring much more hurricane activity. Now sea surface temperatures can be affected, we think, by different processes, greenhouse warming, one, but also these multi-decadal variations that I was talking about, and over the past several decades, perhaps the aerosol effects. That’s why I say, ‘it depends.’

Just the presence of those warm temperatures, at the moment, makes those areas more conducive for sustaining high intensity. There’s a kind of a recipe for intensification, and warm sea surface temperatures is just one of the ingredients. It also depends on the change in the temperature, with height, the stability of the atmosphere, and also wind shear. If you have a high wind shear situation, that’s less conducive for hurricane development. It also depends on having high levels of moisture in the atmosphere, so the atmosphere is not too dry. So you have one of these dry air outbreaks coming off of the Sahara or something, that would not be very conducive for development. If it’s just a shallow layer of warm water, and underneath it there’s cold water, well, that’s not as conducive for hurricane development, because the hurricane could just mix the ocean and bring up that cold water and sort of self-limit its intensity in that way.

But if the warm anomalies are very deep, then that’s an ingredient for more explosive hurricane development. For example, some of these warm core rings that sometimes form in the Gulf of Mexico, those are sometimes referred to as hazards in the Gulf of Mexico, because it’s a deep layer of warm water that can provide a lot of fuel for a hurricane that goes over the top.

McKenzie

So hurricanes are getting more intense? And that is attributable to climate change?

Knutson

Our simulations suggests that hurricanes will become more intense with greenhouse warming. The magnitude of that signal from our modeling studies tends to run in somewhere like one to 10 percent for a two-degree Celsius warming scenario. So with the amount of warming today, we’re talking somewhere between a fraction of a percent and three or four percent. So, if that’s the size signal—and we could be wrong, maybe the world is more sensitive or less sensitive—but if that’s the size of the signal we’re looking for, it is a challenge, I think, to find such a signal in observed trends.

Our methods of measuring hurricane intensity have changed over time, our ability to estimate intensities have changed over time, especially over the open basin. That limits the length of the record that we have and makes it harder to detect long term trends confidently.

The case of rapid intensification is an interesting one. I was the co-author of a paper that came out a year or so ago in Nature Communications, looking at increased rapid intensification globally, and we had an earlier study looking in the Atlantic basin. We think that the increase in rapid intensification that we’ve seen is unusual compared to what we would expect from natural variability, at least according to one model that we’re testing. So that’s something which is suggesting there may be an emerging signal. And it’s in the same direction that we expect—due to greenhouse warming, we expect that greenhouse warming will lead to more rapid intensification. But we haven’t quite tied all the pieces of the puzzle together to make a very confident statement. Partly because there’s still these uncertainties in how much of a role natural variability is playing. And we don’t have very clean experiments that we can use for this metric for attribution yet, but there are at least some indications of an emerging anthropogenic signal related to intensity. In this case, rapid intensification.

The other one I mentioned—the increasing fraction of observed hurricanes that are at Category 3 or higher—is related to intensity change. Because if you have a shift toward greater intensities, especially if you have a shift in the probability distribution of hurricane intensities toward higher intensities, you expect a greater fraction of hurricanes will pass that Category 3 threshold. And over the past four decades we have seen an increase in the fraction of storms that are Category 3 or higher. So that may be an indication of an emerging anthropogenic signal, but we’re not making very confident statements about it yet, because we don’t have careful studies of the size of its signal to expect in the real world, given other things that have been going on besides greenhouse warming in these basins, namely changes in aerosols. It’s kind of a work in progress, I’d say.

McKenzie

Scientists have said that El Niño is here now—is that a factor in greater or more intense hurricane activity?

Knutson

During El Niño years, you tend to have fewer hurricanes in the Atlantic basin. But we’re also in a situation where we have strong warm anomalies in the Atlantic basin. So that kind of cuts the other way. You have different factors going on in the in the same year. This is related more to the seasonal hurricane prediction problem for the Atlantic basin.

McKenzie

So this may be out of left field, but much has been made this summer of the possibility of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation collapsing sometime this century. Hypothetically, if that happened, what might that do to hurricane activity?

Knutson

Well, we haven’t run experiments with that circulation collapsed. But these multi-decadal fluctuations in the AMOC that I’ve been talking about—when the AMOC is relatively strong state, that’s when we tend to have more active hurricane periods, and when they’re in a negative phase of that multi-decadal variability, that’s when we can have less activity.

But that’s just looking at the multi-decadal case, so I don’t want to push that too far.

McKenzie

Is there anything else you would like to add?

Knutson

There’s one observational finding—we’re not quite sure what it means yet—but there has been a study indicating that tropical cyclones are slowing down. The ones that make landfall in the United States are going more slowly as they go across the land. Since 1900, the slowdown has occurred in the data. But we’re not really sure why or whether that’s related to greenhouse warming or something else, or a data problem. But that’s something we want to keep an eye on, because if storms slow down, they will be dumping more rain in a given location—an extreme example, of course, being something like Hurricane Harvey, which stalled for several days near Houston, causing lots of flooding problems.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: climate change, climate crisis, extreme weather, global warming, tropical storms

Topics: Climate Change