Wonder in the time of climate crisis

By Jessica McKenzie | September 20, 2023

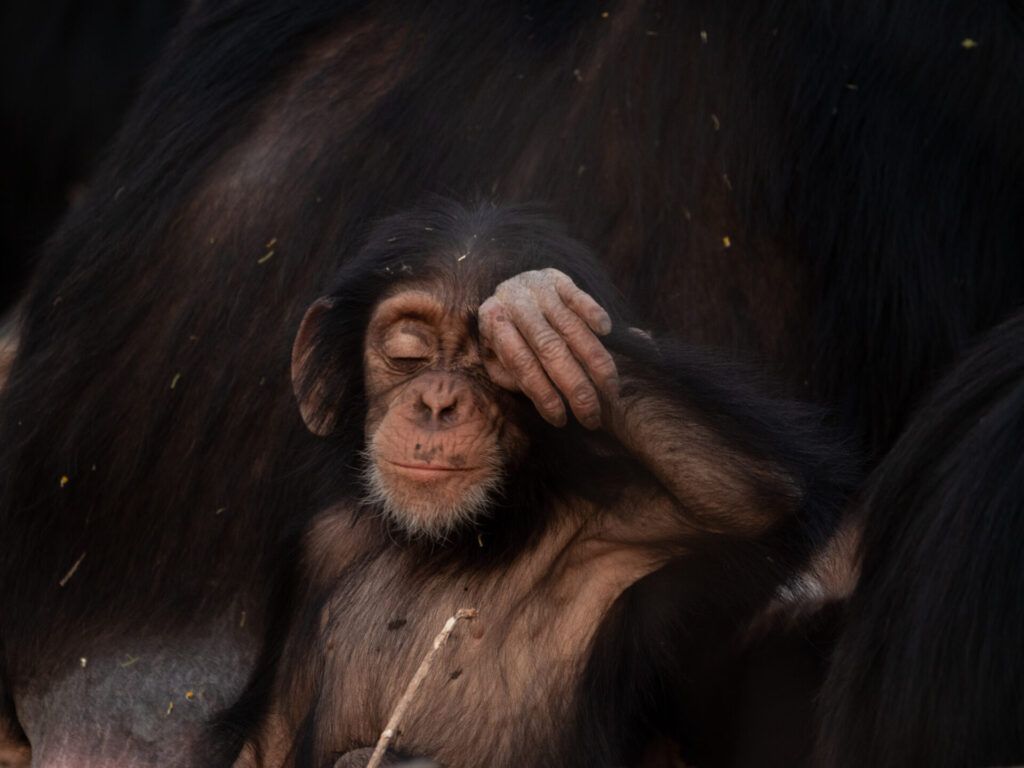

A young chimpanzee feeling the heat. During Fongoli's dry season, temperatures can reach as high as 48 C (120 F). (Fongoli, Senegal) Credit: Courtesy of Passion Planet Ltd.

A young chimpanzee feeling the heat. During Fongoli's dry season, temperatures can reach as high as 48 C (120 F). (Fongoli, Senegal) Credit: Courtesy of Passion Planet Ltd.

I was prepared to loathe the new nature docuseries from PBS, “Evolution Earth.”

The press release crowed that the series “reveal[s] animals keeping pace with a planet changing at superspeed” and “tells a tale of resilience that redefines our understanding of evolution and hints at how nature can show a path towards a sustainable future for Planet Earth.”

This copy flew in the face of at least one article that recently passed through my inbox, which reported that even African wild dogs, a species adapted to the warm tropics, were suffering from hotter temperatures. Researchers found fewer pups were surviving to adulthood; the time between litters was getting longer; and adult survival was lower after bouts of hot weather. And that’s just one example of a species struggling to adapt to a changing climate. Certainly, the promotional materials made no mention of the ongoing extinction crisis, in which more than one million species are teetering on the brink of nonexistence.

The last thing society needed, I thought, was a feel-good series about how the animals will prevail during the climate and biodiversity crisis, while masking, circumventing, or denying the full extent of the damage humans have wrought on the Earth and its ecosystems.

But “Evolution Earth” walks a precarious tightrope, acknowledging irreversible losses in the same breath as it celebrates the unexpected and, yes, even hopeful adaptations of a few select species around the globe.

Each episode opens with the same introductory remarks, including the fact that humans are changing the climate 170 times faster than is natural—a jaw-dropping statistic apparently gleaned from a 2017 paper published in The Anthropocene Review.

The series accepts climate change as a given but doesn’t dwell on why it’s happening or how to stop it, at least not in the first four episodes: ‘Earth,’ ‘Islands,’ ‘Heat,’ and ‘Ice.’ (A screener for the finale, ‘Grasslands,’ wasn’t available.)

Instead, the series is preoccupied with the ways species have adapted to extreme environments, whether over hundreds of thousands of years or a matter of weeks, and what animal behaviors can tell us about the changing climate.

The first animal introduced is the savanna chimpanzee in Senegal, which has a number of tricks to survive the hot, dry savanna: using sticks to fish for termites, a good source of protein; digging rudimentary wells to filter stagnant water through sand; and walking upright more frequently than their forest relatives. These are remarkable behaviors that primatologists use to study and make hypotheses about early hominins. But after marveling at what the savanna chimp can do to survive, the show concludes that segment with the observation: “With temperatures here now predicted to rise nearly three degrees in the next two decades, these chimps are in a race against time.”

The show also features species evolving on far shorter time scales, like the Silver Key anole, a kind of lizard found in the Turks and Caicos Islands. After two Category 5 storms swept over the islands in 2017, biologist Anthony Herrel, a researcher with the French National Centre for Scientific Research, found that the lizard population after the storm had longer toes and legs—better for clinging on tree branches during hurricane winds. All it took was two consecutive “selective events” to change the morphology of an entire species. The show uses this to demonstrate that “animals have a far greater ability to adapt to a changing world than we thought.”

‘Evolution Earth’ highlights the pioneering work of Camille Parmesan, one of the first biologists to show a species shifting its range in response to climate change, all the way back in 1996. Parmesan found that the Edith’s checkerspot, a North American butterfly, had moved, on average, some 100 kilometers northwards and 100 meters further up in elevation. But instead of discussing the broader implications of this research—like what happens when species run out of places to move—the show celebrates how well this one species is doing: “Butterflies are more abundant than I’ve ever seen,” Parmesan gushes.

The script, narrated by host Shane Campbell-Staton, an evolutionary biologist and assistant professor at Princeton, is often folksy, and sometimes oversimplified (think: referring to Charles Darwin as “Chuck D,” or to aggressive animal behavior as “prison rules”).

Where other nature series often feature animals in mostly pristine, remote places, relegating all signs of human presence out of the frame, “Evolution Earth” splices its remarkable wildlife footage with interviews with scientists and other experts in the field. These experts are depicted as friendly, approachable, and nonthreatening—the opposite of talking heads in an ivory tower. For example, in the first episode, the show introduces primatologist Jill Pruetz while she’s swatting flies away from her face (she’s not the last scientist shown blinking bugs out of her eyes) and then zooms in on her chimpanzee tattoo. The unspoken message? ‘Scientists: They’re just like us.’

However, giving so much airtime to scientists allows the show’s creators to keep Campbell-Staton’s script safe and generally hopeful and upbeat, while also airing some more extreme warnings.

“Everything that we love dearly was born out of a stable climate. So, as we destabilize it, the foundations of society that are reliant on a stable climate will start to deteriorate, and we’re already starting to see that,” Parmesan soberly tells the camera. “Will it be too late? That’s the million-dollar question. Life on earth will continue. Will humans continue? Probably not.”

While it can be hard to remember in the thick of climate crisis, a little awe at the wonders of nature can go a long way. Marveling at the resiliency of (a select few) species isn’t the same thing as denying that the climate or extinction crisis exists.

And though the creators have a light touch with the doom and gloom, they still allow scientists to sound the alarm bell, none more succinctly than polar bear biologist Alysa McCall: “People are getting pissed…I’m getting pissed.”

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: animals, biodiversity, climate crisis, documentary, nature, resiliency, review, the end of nature

Topics: Climate Change