During an ‘epidemic’ of news avoidance, moderation is key

By Susan D’Agostino | June 20, 2022

Newsstand. Credit: Claudio Schwarz. Unsplash License. https://unsplash.com/photos/C-F0o855g74

Newsstand. Credit: Claudio Schwarz. Unsplash License. https://unsplash.com/photos/C-F0o855g74

Headlines today spout a firehose of news stories about crises, including Russia’s war in Ukraine, the COVID-19 pandemic, systemic racism, climate change, political upheaval, misogyny, US gun violence, and more. At the same time, public trust in journalism is low and news avoidance is high and increasing, according to a report released last week by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University. If journalism, as the saying goes, is the “first rough draft of history,” this confluence raises concern. An engaged public, informed by independent, quality journalism, is vital both in the present moment and for later drafts of history. As multiple global crises unfold amid changing narratives, news moderation, rather than news avoidance, may be key.

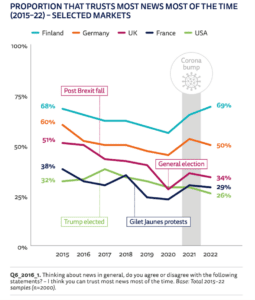

News avoidance is high and increasing. Reuters’ annual report surveyed more than 93,000 people in 46 countries. Finnish citizens reported the highest levels of trust (69 percent) while Americans reported the lowest (26 percent). Meanwhile, those who selectively avoid the news “often or sometimes” rose dramatically across the surveyed countries in the past five years, including having doubled in Brazil and Britain (to 54 and 46 percent respectively).

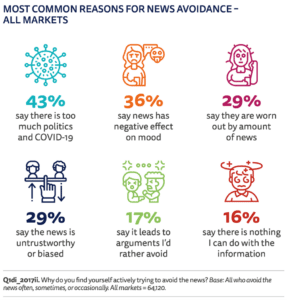

Just under half of respondents (43 percent) reported that they found the news, especially concerning COVID-19, repetitive. More than one-third (36 percent) reported they found the news too depressing, while just under one-third (29 percent) distrusts the news. Some found the news too hard to understand (8 percent)—a sentiment felt even more strongly among young readers (15 percent).

Some long-trusted outlets experienced precipitous declines in public trust; only 55 percent of respondents reported trusting the BBC, for example, as opposed to the 75 percent who did five years ago. Another problem spot is the United States, where the Reuters report found that the best-known journalists are prized for their strong opinions—think Tucker Carlson of Fox News—rather than for their impartiality.

Kenyans and Nigerians reported the highest concern about false and misleading news (72 percent) while Germans and Austrians reported the lowest concern (32 and 31 percent respectively).

Though today’s news environment offers unprecedented access to content, the United States, Japan, United Kingdom, France, and Australia are home to growing populations of people who are disconnected from the news. For example, the percentage of Americans who reported not having accessed TV, print, online, social media, or radio news rose fivefold—from 3 percent in 2013 to 15 percent in 2022. Only a few countries, including Portugal, Finland, South Africa, Nigeria, and Kenya, were well connected, with 2 percent or less reporting no access.

News moderation, not avoidance, is key. So is quality. After Russia invaded Ukraine in late February, many people initially (and dramatically) increased their news consumption before experiencing news fatigue and opting for selective avoidance, according to the Reuters report. This all-or-nothing approach does not serve the individual reader, who is alternately either overwhelmed by too much news or uninformed by too little. It also does not serve governance around the world, which relies on engaged world citizens to help drive conversations about how to solve dire problems.

To avoid being overwhelmed by the 24-7 firehose of internet-based content, news consumers may benefit from a deeper understanding what journalism is—and isn’t. A public health, environmental, political, or other narrative that changes over time does not necessarily serve as evidence that earlier stories on the topic were written to mislead. Rather, earlier stories may have offered an understanding of what was known at the time. Think back to the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic in which public health messaging about masks went from “don’t wear” to “must wear.” Reputable journalists work to get accurate information from experts to the public as soon as possible, and sometimes that information changes for legitimate reasons.

But news stories that change for valid reasons are categorically different from “news stories” written to intentionally mislead. Here, the reputation of the news source matters. But even readers who subscribe to trusted news sources may inadvertently allow “junk” news to creep in by way of passive doomscrolling on social media. Those who forgo that kind of 24-7, IV-drip of news and instead make deliberate decisions about when to tune in may avert a feast-or-famine news diet. Such an approach may also minimize the potential feeling that news is too repetitive. That approach can also give readers time to understand context and controversy.

When news breaks on a topic for which a reader has little background, news stories written as “explainers” or in question-and-answer formats may offer useful on-ramps. Here too, a deliberate approach from the start may enhance a reader’s baseline knowledge, which can help sustain their engagement in the conversation.

And what to do when a favored outlet disappoints, as apparently happened for many BBC readers responding to this survey? Here, another dietary metaphor may help. Instead of abandoning news altogether, readers might diversify their news diet. The same advice applies when a country’s news culture has blind spots—such as the premium placed in some US news markets on strong opinions rather than impartiality.

Journalism, by way of that “first rough draft of history” analogy, is a place where truth may originate. See, for example, the Bulletin’s 1978 cover story, “Is mankind warming the Earth?,” which was published during a time when few outlets were investigating climate change. Journalism also offers public officials a nudge when warranted.

Citizens around the world can stay informed, avoid repetition, and preserve their mental health by identifying a news consumption pace they can sustain over the long haul—and by making sure the news diet they consume is healthy and well-rounded. This way, they will not miss important stories. In turn, they will also be present when an important story needs them to raise their voices.

% of people to trust most news most of the time

69%??

61%??

58%????

57%??

56%??

53%??

52%??

51%??

50%????

48%??

46%??

44%??

43%??

42%??

41%????????

39%??

38%??

37%????

36%????

35%????

34%????

33%??

30%??

29%??

27%????

26%????? More on #DNR22https://t.co/5BaaVS45lg

— Reuters Institute (@risj_oxford) June 16, 2022

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: climate change, disruptive technology, journalism, news, nuclear risk

Topics: Analysis, Climate Change, Disruptive Technologies, Nuclear Risk, Nuclear Weapons

Excellent analysis. I for one have weaned myself off the overly dramatic news sources and and found myself at greater peace. I stay informed by the updates received on email and from some social media.

The ABC station in Houston Tdxas morning News always seems to lead with this shooting, that shooting, this murder, that murder, this road rage incident, then about politics, Ukraine war, climate issues and pandemic. This is every morning, it gets to be to much so yes turned off. I avoid news too depressing