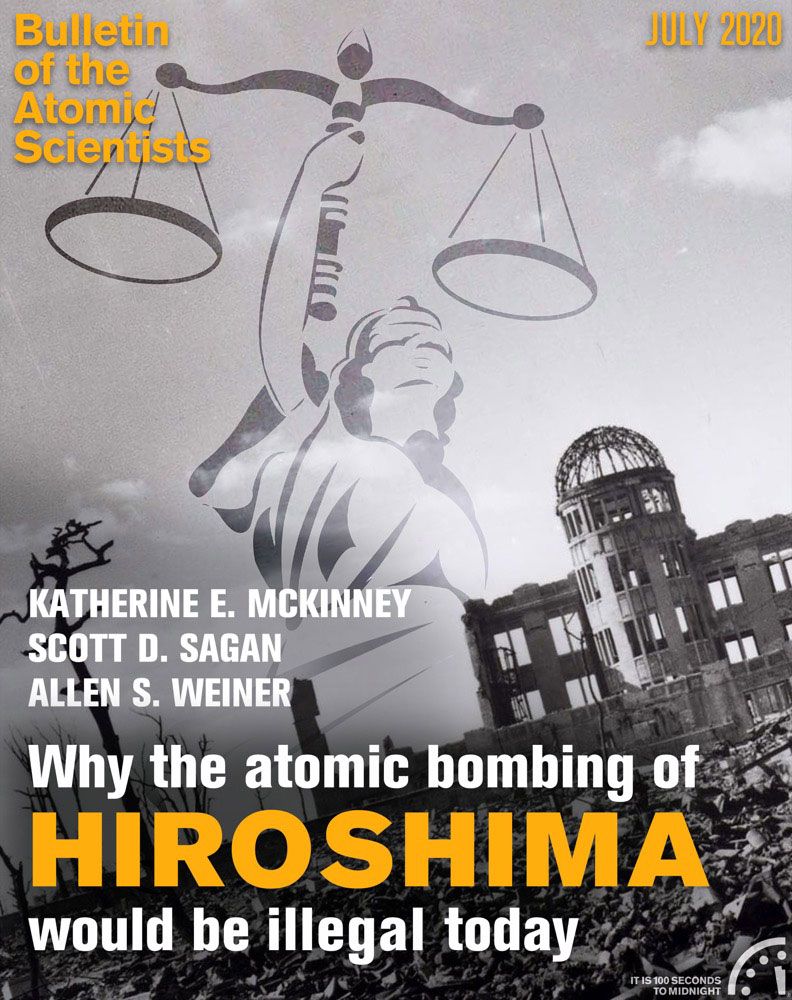

Why the atomic bombing of Hiroshima would be illegal today

By Katherine E. McKinney, Scott D. Sagan, Allen S. Weiner | July 1, 2020

Why the atomic bombing of Hiroshima would be illegal today

By Katherine E. McKinney, Scott D. Sagan, Allen S. Weiner | July 1, 2020

In his first radio address after the bombing of Hiroshima, President Harry S. Truman claimed that “[t]he world will note that the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, a military base. That was because we wished in this first attack to avoid, insofar as possible, the killing of civilians.”[1] This statement was misleading in two important ways. First, although Hiroshima contained some military-related industrial facilities, an army headquarters, and troop loading docks, the vibrant city of over a quarter of a million men, women, and children was hardly “a military base” (Stone 1945). Indeed, less than 10 percent of the individuals killed on August 6, 1945 were Japanese military personnel (Bernstein 2003). Second, the US planners of the attack did not attempt to “avoid, insofar as possible, the killing of civilians.” On the contrary, both the Target Committee (which included Robert Oppenheimer and Maj. Gen. Leslie Groves of the Manhattan Project) and the higher-level Interim Committee (led by Secretary of War Henry Stimson) sought to kill large numbers of Japanese civilians in the attack. The atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima was deliberately detonated above the residential and commercial center of the city, and not directly on legitimate military targets, to magnify the shock effect on the Japanese public and leadership in Tokyo.

What were the legal considerations and moral reasoning used in 1945 to justify the attack on Hiroshima? Could such considerations and reasoning be used again in the future?

Unfortunately, the law of armed conflict regarding aerial bombardment was not well-developed during World War II, prior to the adoption of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and the 1977 Additional Protocols. There was no formal legal analysis of the attack options contemplated in 1945. Nonetheless, intuitive moral concerns and background legal principles were often raised in the secret discussions among American military officers, nuclear laboratory scientists, and high-level political leaders planning the attack. What the archival record makes clear is that such concerns were muted, and when expressed were rejected and then rationalized away. The desire to avoid the US military casualties expected in the planned invasion of Japan, combined with a desire for vengeance against Emperor Hirohito and the Japanese, overwhelmed legal concerns and moral qualms about killing civilians on a massive scale.

Such a nuclear attack would be illegal today. It would violate three major requirements of the law of armed conflict codified in Additional Protocol I of the Geneva Conventions: to not intentionally attack civilians (the principle of distinction or non-combatant immunity); to ensure that collateral damage against civilians is not disproportionate to the direct military advantage gained from the target’s destruction (the principle of proportionality); and to take all feasible precautions to reduce collateral damage against civilians (the precautionary principle).

The role of lawyers in US military planning has grown enormously in recent decades. All military plans, from tactical operations to nuclear war options, are now reviewed by members of the Judge Advocates General Corps (JAGs).[2] This ensures that any contemplated nuclear first strike would receive a formal legal review today, and that such legal objections would be raised.

Yet there is no guarantee that a future US president would follow the law of armed conflict. That is why we need senior military officers to fully understand the law and demand compliance. And that is why we need presidents who care about law and justice in war.

Terror bombing with a legal veneer

The history of the “decision” to drop the bomb has been told many times. But what has been underplayed is how concerns about ethics and law were invoked, but in a muted and often rationalizing manner that had little impact on the targeting of Hiroshima.

Truman’s “military base” claim was consistent with an August 9 Office of War Information memorandum advising that all public announcements state clearly that Hiroshima and Nagasaki (and presumably further atomic attacks on targets in Japan) had “sufficient military character to justify attack under the rules of civilized warfare” (Malloy 2007). Truman’s speech, however, also displayed his retributive instincts and raised Japanese violations of international law as a justification for dropping the bomb: “Having found the bomb we have used it. We have used it against those who attacked us without warning at Pearl Harbor, against those who have starved and beaten and executed American prisoners of war, against those who have abandoned all pretense of obeying international laws of warfare” (Truman 1945).

The international law of armed conflict, however, provided scant guidance on aerial bombardment before and during World War II. The 1907 Hague Conventions regulating traditional ground warfare stated that “the attack or bombardment, by whatever means, of towns, villages, dwellings, or buildings which are undefended is prohibited,” yet military facilities, war-supporting industry, and workers in such plants were considered legitimate military targets.[3] Efforts to negotiate a treaty on aerial bombing failed to reach agreement in the 1920s. Early in the war in Europe, the US Army Air Force focused its attacks mainly on military bases and war-supporting industry sites, but by late 1944, broader “area bombing” was added, with the intent to affect the “morale” of the German population and reduce support for continuing the war.[4] This pattern – focusing on both military-related targets and on trying to create broader psychological effects—was repeated in the strategic bombing campaign against Japan.

Two committees—the Target Committee and the Interim Committee— were convened in the Spring of 1945 to advise US leaders on the atomic bomb. At its May 1945 meetings at Los Alamos, the Target Committee agreed that destruction of the selected target should succeed in “obtaining the greatest psychological effect against Japan:” “In this respect Kyoto has the advantage of the people being more highly intelligent and hence better able to appreciate the significance of the weapon. Hiroshima has the advantage of being such a size and with possible

focusing from nearby mountains that a large fraction of the city may be destroyed” (Derry 1945). Although committee members also described Hiroshima as “an important army depot and port of embarkation in the middle of an urban industrial area” and of “such a size that a large part of the city could be extensively damaged,” they nevertheless recommended Kyoto, the ancient capital, which had less military importance, as the best target of the first atomic bomb.[5] The Target Committee’s priority was also clear in their final recommendation “to neglect location of [military] industrial areas as pin point target, since … such areas are small, spread on fringes of cities and quite dispersed” and instead “to place first gadget in center of selected city.”[6]

The prioritization of maximizing the bomb’s “psychological impact,” while still wanting to include destruction of military targets, was also present in the Interim Committee meetings later that month. According to the minutes of the May 31 meeting, Secretary Stimson concluded

“that we could not give the Japanese a warning; we could not concentrate on a civilian area; but that we should seek to make a profound psychological impression on as many of the inhabitants as possible… [T]he Secretary agreed that the most desirable target would be a vital war plant employing a large number of workers and closely surrounded by workers’ houses.”[7]

This was an endorsement of terror bombing with a legal veneer.

Officials in Washington and Los Alamos had discussed the idea of a “demonstration strike”—providing a warning and then dropping the bomb on an uninhabited area or purely military target like a navy base—with many objections raised: if the bomb did not detonate, Japan would be not demoralized, but encouraged to continue fighting; the Japanese might place allied prisoners of war at the site; and, moreover, the bombs had been designed to be dropped from 30,000 feet and explode in the air, rather than closer to the ground or underwater, which would be necessary to maximize damage against “hardened” targets like a naval base or the Japanese fleet.[8] Lingering moral inhibitions and legal concerns were reduced by June 6, when the Interim Committee reported that “while recognizing that the final selection of the target is essentially a military decision, [the committee] recommended that … [the bomb] should be used on a dual target, that is, a military installation or war plant surrounded by or adjacent to homes or other buildings most susceptible to damage.”[9]

The prioritization of civilian targeting was made explicit by Groves in his memoirs: “[T]he targets chosen should be places the bombing of which would most adversely affect the will of the Japanese people to continue the war. Beyond that, they should be military in nature, consisting either of important headquarters or troop concentrations, or centers of production of military equipment and supplies.”[10]

These statements make clear that killing large numbers of civilians was the primary purpose of the attack; destruction of military targets and war industry was a secondary goal and one that “legitimized” the intentional destruction of a city in the minds of some participants. In fact, the crew of the Enola Gay, which in the end was permitted to pick the aim point, chose the easily recognizable t-shape, three-way Aioi Bridge at the center of Hiroshima. More than 70,000 men, women, and children were killed immediately; the munitions factories on the periphery of the city were left largely unscathed (United States Strategic Bombing Survey 1946).

The myth of unconditional surrender

Secretary Stimson made two requests of President Truman at Potsdam in July 1945. First, he urged that Kyoto be taken off the target list. Stimson had long favored sparing the ancient capital and, according to his diary, told Truman that “the bitterness which would be caused by such a wanton act might make it impossible during the long post-war period to reconcile the Japanese to us in that area rather than to the Russians” (Office of the Historian 1945). Second, Stimson recommended that the United States modify the unconditional surrender terms to signal to the Japanese government that Emperor Hirohito would not be put on trial after the war.

Truman accepted his first recommendation, but rejected the second. Truman had committed himself to unconditional surrender in his first address to Congress in April 1945, a speech which also displayed his strong retributive instincts: “We do not wish to see unnecessary or unjustified suffering. But the laws of God and of man have been violated and the guilty must not go unpunished” (Truman 1945b). The US public held similar views: A private June 1945 State Department poll reported that when asked “what do you think we should do with the Japanese emperor after the war,” 36 percent of the public answered “kill him, torture, starve him,” 24 percent said “punish or exile him,”17 percent answered “try him” or “treat him as a war criminal,” and only 7 percent answered “nothing” or “use him as a puppet” (Brands 2006). With Secretary of State James Brynes’ support, but against Stimson’s advice, Truman insisted that the Potsdam Declaration not mention the Emperor but simply state that “[t]here must be eliminated for all time the authority and influence of those who have deceived and misled the people of Japan into embarking on world conquest,” and warned that “stern justice shall be meted out to all war criminals” (Potsdam Declaration 1945).

This decision was critical. On August 10, after the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Soviet entry into the war, the Japanese government declared it was ready to surrender, but only on the condition that nothing in the peace agreement “prejudices the prerogatives of his majesty (Emperor Hirohito) as a sovereign ruler” (Bix 2000: 517). In response, Truman signaled to the Japanese government on August 11, through a carefully crafted letter written by Secretary of State James Byrnes, that the emperor would not be subject to war crimes trials.[11] The Byrnes letter, while stating that the “authority of the emperor” would be “subject to the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers,” also promised that “the ultimate form of government of Japan shall, in accordance with the Potsdam Declaration, be established by the freely expressed will of the Japanese people” (Byrnes 1945). Hirohito understood that a private deal had been offered. On August 14, the Emperor joined the “peace party” and ordered his government to surrender immediately.[12]

Although Truman publicly insisted that this act constituted “a full acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration which specified the unconditional surrender of Japan,” he was a bit more candid about the compromise in a confidential diary entry:

They wanted to make a condition precedent to the surrender. Our terms are unconditional. They wanted to keep the Emperor. We told ‘em we’d tell ‘em how to keep him.[13]

It was only in an interview years later that Truman would acknowledge, without the hostility and bravado, that “he [Hirohito] was told that he would not be tried as a war criminal and that he would be retained as emperor.”[14] After the war, Stimson also acknowledged that “history might find that the United States, by its delay in stating its position, had prolonged the war” (Stimson and Bundy 1947: 629).

As is true with all counterfactuals, we can’t know with certainty whether the Japanese government would have surrendered without the dropping of the bomb if the compromise regarding the emperor had been offered earlier. Historians and political scientists offer divergent and nuanced judgements.[15] Among the many tragedies of Hiroshima, however, is that Truman refused to alter the unconditional surrender terms and try this diplomatic maneuver earlier.

Scenarios resembling the Hiroshima dilemma today

Could a nuclear attack, like the one that destroyed Hiroshima, be legally justified today? In 2017, then STRATCOM Commander General John E. Hyten described how he thought about the rule of law:

[E]very year I get trained in a law of armed conflict. And the law of armed conflict has certain principles and necessities, distinction, proportionality, unnecessary suffering. All those things are defined. All those things are defined. And we get, you know, for 20 years it was the William Calley, My Lai thing that we were trained on because if you execute an unlawful order you will go to jail. You could go to jail for the rest of your life. It applies to nuclear weapons…I provide advice to the president. He’ll tell me what to do and if it’s illegal, guess what’s going to happen…I’m going to say, Mr. President, it’s illegal. And guess what he’s going to do? He’s going to say what would be legal? And we’ll come up with the option of a mix of capabilities to respond to whatever the situation is” (Hyten 2017).

What advice should a JAG lawyer provide to a senior officer if a president issued an order to drop a nuclear bomb on a city in Iran or North Korea or another foreign country, in an attempt to coerce its government into accepting unconditional surrender by killing large numbers of civilians?

First, the president should be told that although the United States did not ratify, and is therefore not a party to, Additional Protocol I of the Geneva Convention, the US government has long accepted that the principles of distinction, proportionality, and precaution that were codified in Protocol I reflect binding customary international law and thus are legal obligations (Matheson 1987). In addition, the Obama Administration clearly stated in 2013 that these obligations apply to nuclear weapons: “[A]ll plans must also be consistent with the fundamental principles of the Law of Armed Conflict. Accordingly, plans will, for example, apply the principles of distinction and proportionality and seek to minimize collateral damage to civilian populations and civilian objects. The United States will not intentionally target civilian populations or civilian objects” (U.S. Department of Defense 2013). The Trump administration’s 2018 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) reaffirmed the US commitment to “adhere to the law of armed conflict” in any “initiation and conduct of nuclear operations” (US Department of Defense 2018).

A nuclear attack deliberately aimed at the center of a city to maximize civilian casualties would clearly violate the principle of distinction, enshrined in Article 48 of Additional Protocol I, which requires governments to “distinguish between the civilian population and combatants and between civilian objects and military objectives” and then direct “operations only against military objectives” (International Committee of the Red Cross 1977a). Article 52 (2) also clearly limits legitimate military objectives “to those objects which by their nature, location, purpose or use make an effective contribution to military action and whose total or partial destruction, capture or neutralization, in the circumstances ruling at the time, offers a definite military advantage” (International Committee of the Red Cross 1977). Moreover, the Defense Department’s Law of War Manual specifically precludes attacks designed to diminish “the morale of the civilian population and their support for the war effort” (General Counsel Of The Department of Defense 2016a). Senior officers would be legally required to disobey a president’s order to intentionally target the center of a city as “manifestly” or “patently” illegal” (Solis 2016: 391-393).

What if in a future conflict, the president instead ordered a nuclear strike against a munitions factory, a regional army headquarters, or a naval loading-dock, all legitimate military targets, inside the city?

In this scenario, the principles of proportionality and precaution would apply. JAG lawyer Theodore Richard correctly notes that “the modern approach” requires decision makers to weigh the expected collateral damage against solely the importance of the destruction of legitimate military targets (Richard 2016: 974). The proportionality principle is expressed in Article 51(5) of Additional Protocol I, which prohibits attacks “which may be expected to cause incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians, damage to civilian objects, or a combination thereof, which would be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated” (International Committee of the Red Cross 1977b).

Regarding the munitions factory, in 1945, munitions workers were considered a legitimate military target. Today they are not. The Department of Defense Law of War Manual clearly states: “Provided such workers [‘workers in munitions factories’] are not taking a direct part in hostilities, those determining whether a planned attack would be excessive must consider such workers, and feasible precautions must be taken to reduce the risk of harm to them” (General Counsel Of The Department of Defense 2016b). The first part of this Defense Department rule would require that the direct military benefit of destroying that munitions factory must outweigh the collateral damage from the use of the nuclear weapon. It is highly unlikely that any single munitions factory (with the possible exception of an adversary’s nuclear weapons production facility) would meet that proportionality criteria. It is also highly unlikely that the direct military benefit of destroying loading docks or a regional army headquarters could be high enough to be considered proportional.

The second part of the Defense Department statement reflects the requirement of Article 57 of Additional Protocol I that “those who plan or decide upon an attack” must “take all feasible precautions in the choice of means and methods of attack with a view to avoiding, and in any event minimizing, incidental loss of civilian life” (International Committee of the Red Cross 1977c). The precautionary principle requirement in this scenario means that it would be illegal for the United States to use a nuclear weapon against the munitions factory, army headquarters building, or navy docks if they could be destroyed with high confidence by conventional weapons, which would minimize collateral damage (Lewis and Sagan 2016). The president’s order should thus be deemed illegal under this legal principle as well.

Ending wars justly

A nuclear strike against a legitimate military target could be legal only if it met all three criteria: no intentional targeting of civilians, absence of disproportionate collateral damage, and with all feasible precautions made to reduce collateral damage. Many scholars and pundits continue to claim that the Hiroshima nuclear bombing was legitimate, however, implying that the attack— and presumably other attacks like it in the future—can be justified on the grounds that it saved many American soldiers lives, even at the cost of many foreign civilians lives.[16] Some more cosmopolitan scholars, like Gabriella Blum, have acknowledged that Hiroshima would be considered a war crime today. Blum, however, argues that the Hiroshima bombing nonetheless could be justified as the “lesser evil,” if decision-makers had used the atomic bomb to prevent even more Japanese civilians from perishing in continued US conventional bombing and an invasion than they estimated would die in the Hiroshima attack (Blum 2010).

It is certainly legitimate to factor saving American soldiers’ lives into the difficult balancing act of applying the principle of proportionality.[17] And it is also appropriate to consider the lives of foreign civilians who might die in conventional military strikes before a war ends. We think, nevertheless, that such claims about the legitimacy of the attack on Hiroshima (or future Hiroshima-like attacks) are wrong because they assume that unconditional surrender was the only acceptable outcome.

The principles governing the terms states may impose as conditions for ending war—whether thought of under the framework of jus ad bellum proportionality or jus post bellum (justice after war)—comprise one of the least well-developed areas of just war doctrine. The law, too, provides little clarity; the Geneva Conventions are silent on what surrender terms are acceptable to demand of an unjust aggressor. There is a widespread view that states fighting a just war against an aggressor have a right not just to restore borders, and thus the pre-war status quo, but to ensure that the aggressor cannot repeat its offense. According to many experts, in a war against an extremely aggressive state, imposing regime change may be justified.[18]

But there are limits on the ends states may seek in terminating wars. As the Defense Department Law of War manual notes, “the overall goal of the State in resorting to war should not be outweighed by the harm that the war is expected to produce”( General Counsel Of The Department of Defense 2016c). This proportionality principle applies at the end of a war as well. Leaders must evaluate whether civilian collateral damage in bello would be disproportionate to the benefit of achieving regime change against aggressor states post bellum. In 1945, as well as in dark future scenarios, abandoning the quest for unconditional surrender should be a price worth paying to prevent the use of nuclear weapons and the mass killing of foreign non-combatants.

To stay the hand of vengeance

In any future war, if the United States finds itself in a dire strategic situation like the one it faced in August 1945—contemplating a major invasion of a hostile enemy country in which many US troops would be killed—there is no absolute guarantee that the law would be followed. In such desperate circumstances, many American civilians would support a nuclear first strike, demands for vengeance would be high, and the political pressures to reduce American combatant casualties would be strong.[19] Legal advice would be one constraint on a nuclear attack, but the rules about how to assess the legality of unconditional surrender demands and how to measure compliance with the proportionality principle in ending wars are among the least well-defined aspects of the law of armed conflict. And it is alarming that a lawyer who served recently as the US National Security Advisor—John Bolton—both advocated for a preventive war against North Korea and wrote that “Truman acted decisively and properly to end the war” by dropping the bomb.[20]

Harry Truman’s written press release after the Hiroshima bombing not only claimed that Hiroshima was “a military base,” which would have been a legal target, but it also clearly displayed the retributive instincts and feelings of revenge that colored his thinking:

The Japanese began the war from the air at Pearl Harbor. They have been repaid many fold. And the end is not yet… If they do not now accept our terms they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth (Truman 1945c).

We hope, but cannot know with certainty, that humanitarian principles and the law of armed conflict would reign in a future conflict, even though they did not in 1945. Different presidents clearly hold different views about the law of armed conflict, ranging from reverence to flagrant disregard. Different presidents have different retributive proclivities.

President Barack Obama discussed just war theory and the law of armed conflict in his 2009 Nobel Prize acceptance speech (Obama 2009). Obama also called for a “moral awakening” in his 2016 speech in Hiroshima: “The scientific revolution that led to the splitting of an atom requires a moral revolution as well.”[21] Then-candidate Donald Trump, in contrast, responded to Obama’s Hiroshima visit by tweeting “Does President Obama ever discuss the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor while he’s in Japan? Thousands of American lives lost.”[22] And Trump’s August 2017 threat to North Korea—“North Korea best not make any more threats to the United States… They will be met with fire and fury like the world has never seen”—was an echo of Truman’s statement, a thinly-veiled nuclear first strike threat.[23]

In future wars, public pressures and the all too human instinct for retribution and revenge could encourage a president to target foreign civilians or embrace disproportionate attacks. In dire scenarios, law must stay the hand of vengeance. At such moments, senior military leaders must advise presidents on the law of armed conflict and insist on compliance.

Disclosure

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Funding

No funding of interest was reported by the author.

References

Bass GJ. 2004. “Jus Post Bellum.” Philosophy & Public Affairs 32 (4): 384-412.

Bernstein B. 2003. “Reconsidering the ‘Atomic General’: Leslie R. Groves.” The Journal of Military History 67 (3): 904-905. DOI: 10.1353/jmh.2003.0198.

Bernstein B. 1995. “The Atomic Bombing Reconsidered.” Foreign Affairs 74 (1): 135-153.

Bernstein BJ. 1995. “Understanding the Atomic Bomb and the Japanese Surrender: Missed Opportunities, Little-Known Near Disasters, and Modern Memory.” Diplomatic History 19 (2): 227–273.

Biddle TD. 2002. Rhetoric and Reality in Air Warfare: The Evolution of British and American Ideas about Strategic Bombing, 1914-1945. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press;

International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). 1907. Convention (IV) respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land and its annex: Regulations concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land. October 18. Available at: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/ihl/INTRO/195.

Bix HP. 2000. Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. New York, NY: Harper Collins: 517.

Bix HP. 1996. “Japan’s Delayed Surrender: A Reinterpretation.” in Hogan, M.J. ed. Hiroshima in History and Memory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 80-116.

Blum G. 2010. “The Laws of War and the Lesser Evil.” Yale Journal of International Law 35 (1): 1-69.

Bolton J. 2016. “Obama’s shameful apology tour lands in Hiroshima.” New York Post, May 26. Available at: https://nypost.com/2016/05/26/obamas-shameful-apology-tour-lands-in-hiroshima/.

Brands H. 2006. “The Emperor’s New Clothes: American Views of Hirohito after World War Two” The Historian, 68 (1): 4. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24453490?seq=4 – metadata_info_tab_contents

Byrnes JF. 1945. United States Department of State, [Letter from U.S. Secretary of State James F. Byrnes to The Secretary of State to the Swiss Chargé Max Grässli]. Foreign Relations of the United States: diplomatic papers, 1945. The British Commonwealth, the Far East (1945): 631-632. Accessed May 14, 2020 at: http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/FRUS/FRUS-idx?type=turn&entity=FRUS.FRUS1945v06.p0644&id=FRUS.FRUS1945v06&isize=M.

Crawford NC. 2013. Accountability for Killing: Moral Responsibility for Collateral Damage in America’s Post 9-11 Wars. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Derry JA. 1945. “Summary of Target Committee Meetings on 10 and 11 May 1945,” Memorandum from Major J.A. Derry to Dr. N.F. Ramsey to General L.R. Groves, May 12, RG 77, MED Records, Top Secret Documents, File no. 5d (copy from microfilm), The National Security Archive, Washington, D.C. Available at: https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nukevault/ebb525-The-Atomic-Bomb-and-the-End-of-World-War-II/documents/011.pdf: 6.

Dill J. 2015. Legitimate Targets? International Law, Social Construction, and US Bombing. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Dower, J.W. 1995. “Triumphal and Tragic Narratives of the War in Asia.” The Journal of American History 82 (3): 1124-1135. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2945119.

Dower JW. 2010. Cultures of War: Pearl Harbor/Hiroshima/9-11/Iraq. New York, NY: W.W. Norton: 238-239.

Fabre C. 2015. “War Exit.” Ethics 125: 631-652.

Friedman G. 2016. “Hiroshima and Nagasaki: A Moral Necessity.” Geopolitical Futures, May 26. Available at: https://geopoliticalfutures.com/hiroshima-and-nagasaki-a-moral-necessity/.

General Counsel of the Department of Defense. 2016a. Department Of Defense Law Of War Manual. 5.6.7.3. Available at: https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/DoD%20Law%20of%20War%20Manual%20-%20June%202015%20Updated%20Dec%202016.pdf?ver=2016-12-13-172036-190.

General Counsel Of The Department of Defense. 2016b. Department Of Defense Law Of War Manual. 5.12.3.3. Available at: https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/DoD%20Law%20of%20War%20Manual%20-%20June%202015%20Updated%20Dec%202016.pdf?ver=2016-12-13-172036-190.

General Counsel Of The Department of Defense. 2016c. Department Of Defense Law Of War Manual. 3.5.1, p. 86. Available at: https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/DoD%20Law%20of%20War%20Manual%20-%20June%202015%20Updated%20Dec%202016.pdf?ver=2016-12-13-172036-190.

Gordin MD. 2007. Five Days in August: How World War II Became a Nuclear War. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press: 29-38.

Groves LR. 1962. Now it Can Be Told: The Story of the Manhattan Project. New York, NY: De Capo Press.

Hasegawa T. 2005. Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press: 215-251.

Hasegawa T. 2007. “The Atomic Bombs and the Soviet Invasion: Which Was More Important in Japan’s Decision to Surrender?” in Hasegawa, T. ed. The End of the Pacific War: Reappraisals. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press: 113-144.

Heinrichs W and Gallicchio M. 2017. Implacable Foes: War in the Pacific, 1944-1945. New York, NY: Oxford University Press: 564-586.

Hyten JE. 2017. “2017 Halifax International Security Forum Plenary 2 – Nukes: The Fire and the Fury.” Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada: Halifax International Security Forum. Available at: https://halifaxtheforum.org/media_library/2017-plenary-2-nukes-fire-fury/.

International Committee of the Red Cross. 1977a. Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflict (Protocol I), Article 48. June 8. Available at: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/ihl/WebART/470-750061?OpenDocument.

International Committee of the Red Cross. 1977b. Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflict (Protocol I), Article 51(5). June 8. Available at: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/ihl/WebART/470-750065.

International Committee of the Red Cross. 1977c. Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflict (Protocol I), Article 57(2) (a)(ii). June 8. Available at: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/ihl/WebART/470-750073?OpenDocument.

Koshiro Y. 2013. Imperial Eclipse: Japan’s Strategic Thinking about Continental Asia before August 1945. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Lewis JG and Sagan SD. 2016. “The Nuclear Necessity Principle: Making US Targeting Policy Conform with Ethics & the Laws of War.” Daedalus 145 (4): 62-74. DOI: 10.1162/DAED_ a_00412.

Luban D. 2014. “Risk Taking and Force Protection.” in Benbaji, Y. and N. Sussman eds. Reading Walzer. New York, NY: Routledge.

Malloy SL. 2008. Atomic Tragedy: Henry L. Stimson and the Decision to use the Bomb Against Japan. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press: 120-142

Malloy S. 2007. “‘The Rules of Civilized Warfare’: Scientists, Soldiers, Civilians, and American Nuclear Targeting, 1940-1945.” The Journal of Strategic Studies 30 (3): 476. DOI: 10.1080/01402390701343482.

Matheson MJ. 1987. “Remarks on the United States Position on the Relation of Customary International Law to the 1977 Protocols Additional to the 1949 Geneva Conventions,” reprinted in Dupuis, M.P., Heywood, J.Q. and Sarko MYF. 1987. “The Sixth Annual American Red Cross – Washington College of Law Conference on International Humanitarian Law: A Workshop on Customary International Law and the 1977 Protocols Additional to the 1949 Geneva Conventions.” American University International Law Review 2 (2): 426-427.

Memorandum for Mr. Harrison. 1945. memorandum, June 6, 1945, RG 77, MED Records, H-B files, folder no. 100 (copy from microfilm), National Security Archive, Washington, D.C. Available at: https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nukevault/ebb525-The-Atomic-Bomb-and-the-End-of-World-War-II/documents/020.pdf: 1.

Minutes of Third Target Committee Meeting. 1945. meeting notes, May 28, 1945, RG 77, MED Records, Top Secret Documents, File no. 5d (copy from microfilm), The National Security Archive, Washington, D.C. Available at: https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nukevault/ebb525-The-Atomic-Bomb-and-the-End-of-World-War-II/documents/015.pdf: 3.

Notes of the Interim Committee Meeting. 1945. Thursday, 31 May 1945. 10:00 A.M. to 1:15 P.M.- 2:15 P.M. to 4:15 P.M., meeting notes, May 31, 1945, RG 77, MED Records, H-B files, folder no. 100 (copy from microfilm), The National Security Archive, Washington, D.C. Available at: https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nukevault/ebb525-The-Atomic-Bomb-and-the-End-of-World-War-II/documents/018.pdf: 13-14.

Obama B. 2009. “A Just and Lasting Peace,” Nobel Media, December 10. Available at: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/2009/obama/26183-nobel-lecture-2009/.

Office of the Historian. 1945. “Foreign Relations of the United States: Diplomatic Papers, the Conference of Berlin (the Potsdam Conference), Volume II.” United States Department of State. Available at: https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1945Berlinv02/d1310.

Orend B. 2000. War and International Justice: A Kantian Perspective. Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Pape R. 1993. “Why Japan Surrendered.” International Security 18 (2): 154-201. DOI: 10.2307/2539100.

Potsdam Declaration. 1945. Proclamation Defining Terms for Japanese Surrender Issued, at Potsdam, July 26. Atomic Heritage Foundation. Available at: https://www.atomicheritage.org/key-documents/potsdam-declaration.

Richard T. 2016. “Nuclear Weapons Targeting: The Evolution of Law and U.S. Policy.” Military Law Review 224 (4): 862-97

Sagan SD and Valentino BA. 2019. “On Reciprocity, Revenge, and Replication: A Rejoinder to Walzer, McMahan, and Keohane.” Ethics & International Affairs 33(4): 473-479. DOI: 10.1017/S089267941900042X.

Sagan SD and Valentino BA. 2018. “Not Just a War Theory: American Public Opinion about Ethics in Combat.” International Studies Quarterly 62 (3): 548-561. DOI: 10.1093/isq/sqy033.

Sagan SD and Weiner AS. 2018. “Bolton’s Illegal War Plan for North Korea,” New York Times, April 6. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/06/opinion/john-bolton-north-korea.html.

Sagan SD and Valentino BA. 2017. “Revisiting Hiroshima in Iran: What Americans Really Think about Using Nuclear Weapons and Killing Noncombatants.” International Security 42 (1): 41-79. DOI: 10.1162/ISEC_a_00284.

Savarese LF and Witt JF. 2017. “Strategy & Entailments: The Enduring Role of Law in the U.S. Armed Forces.” Daedalus 146 (1): 18. DOI: 10.1162/DAED_.

Sherry M. 1989. The Rise of American Air Power: The Creation of Armageddon. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Sigal LV. 1998. Fighting to a Finish: The Politics of War Termination. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Solis GD. 2016. The Law of Armed Conflict: International Humanitarian Law in War (2d ed.). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press: 391-393.

Stephens B. 2015. “Thank God for the Atomic Bomb: Hiroshima and Nagasaki weren’t merely horrific, war-ending events. They were lifesaving.” The Wall Street Journal, August 3. Available at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/thank-god-for-the-atom-bomb-1438642925.

Stimson HL and Bundy M. 1947. On Active Service in Peace and War. New York, NY: Harper & Brothers: 629.

Stone J. 1945. “Memorandum from Colonel John Stone to General Arnold, ‘Groves Project,” Memorandum, July 25, RG 77, MED Records, H-B files, folder no. 100 (copy from microfilm), Washington, D.C. Available at: https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nukevault/ebb525-The-Atomic-Bomb-and-the-End-of-World-War-II/documents/060b.pdf.

Truman HS. 1945a. “Radio report to the American people on the Potsdam Conference.” Harry S. Truman Library & Museum, August 9. Available at: https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/soundrecording-records/sr61-37-radio-report-american-people-potsdam-conference.

Truman HS. 1945b. “First Speech to Congress.” University of Virginia: Miller Center. April 16. Available at: https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/april-16-1945-first-speech-congress.

Truman HS. 1945c. “Statement by President Truman.” Office of the Historian, August 6. Available at: https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1945v06/d401.

United States Strategic Bombing Survey. 1946. The Effects of the Atomic Bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Harry S. Truman Library & Museum, June 30. Available at: https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/library/research-files/united-states-strategic-bombing-survey-effects-atomic-bombs-hiroshima-and?documentid=NA&pagenumber=5: 5, 6, 41.

US Department of Defense. 2013. Report on Nuclear Employment Strategy of the United States Specified in Section 491 of 10 U.S.C. Washington, D.C.: 4-5. Available at: https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a590745.pdf.

US Department of Defense. 2018. Nuclear Posture Review. Washington, D.C.:23. Available at: https://media.defense.gov/2018/Feb/02/2001872886/-1/-1/1/2018-NUCLEAR-POSTURE-REVIEW-FINAL-REPORT.PDF.

Walzer M. 2015. Just and Unjust Wars: A Moral Argument with Historical Illustrations. New York, NY: Basic Books: 109-116.

Wellerstein A. 2020. “The Kyoto Misconception: What Truman Knew, and Didn’t Know, About Hiroshima.” in The Age of Hiroshima eds. Gordin, M.D. and G.J. Ikenberry. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press: 34-55.

Williams PW. 1929. “Legitimate Targeting in Aerial Bombardment,” 23 American Journal of International Law 570.

Notes

[1] See Truman 1945a. For an excellent analysis see Wellerstein 2020: 34-55.

[2] See Richard 2016 and Savarese and Witt 2017.

[3] See International Committee of the Red Cross 1907 and Williams 1929.

[4] See Biddle 2002 and Sherry 1989.

[5] See Derry 1945: 4-5. Kyoto did have some military-related industry, but less than Hiroshima. See Wellerstein 2020: 41.

[6] See Minutes of Third Target Committee Meeting 1945: 3.

[7] See Notes of the Interim Committee Meeting: 13-14.

[8] The best analysis is Malloy 2007.

[9] See Memorandum for Mr. Harrison 1945. (emphasis added)

[10] See Groves 1962. (emphasis added)

[11] For scholarly analysis of Truman’s response see: Bernstein 1995, Hasegawa 2005, Gordin 2007, and Malloy 2008.

[12] On August 12, when a member of the imperial family asked Hirohito if the war would be continued if the kokutai (the imperial national polity) could not be preserved, the emperor replied “of course.” See Bix 2000: 518-519.

[13] Quoted in Heinrichs and Gallicchio 2017: 564-586. Also see Dower 2010: 238-239.

[14] Truman, A Statement, Memoirs: Foreign Policy, Atomic Bomb, Post-Presidential Memoirs, Harry S. Truman Library, as quoted in Hasegawa 2005: 221.

[15] See Bernstein 1995: 135-153; Bix 1996: 80-116; Dower 1995: 1124-1135; Hasegawa 2007: 113-144; Koshiro 2013; Pape 1993: 154-201; and Sigal 1998.

[16] See Friedman 2016 and Stephens 2015.

[17] See Crawford 2013; Dill 2015; Luban 2014; and Sagan and Valentino 2018.

[18] See Bass 2004; Fabre 2015; Orend 2000; and Walzer 2015.

[19] See Sagan and Valentino 2017 and Sagan and Valentino 2019.

[20] See Bolton 2016, and Sagan and Weiner 2018.

[21] See https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/28/world/asia/text-of-president-obamas-speech-in-hiroshima-japan.html.

[22] See https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/736672123012427776.

[23] See https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/08/world/asia/north-korea-un-sanctions-nuclear-missile-united-nations.html.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Geneva Conventions, Hiroshima, just war doctrine, law of armed conflict, nuclear weapons

Topics: Hiroshima & Nagasaki, Nuclear Weapons

“Legality” per se, is determined by the winner!