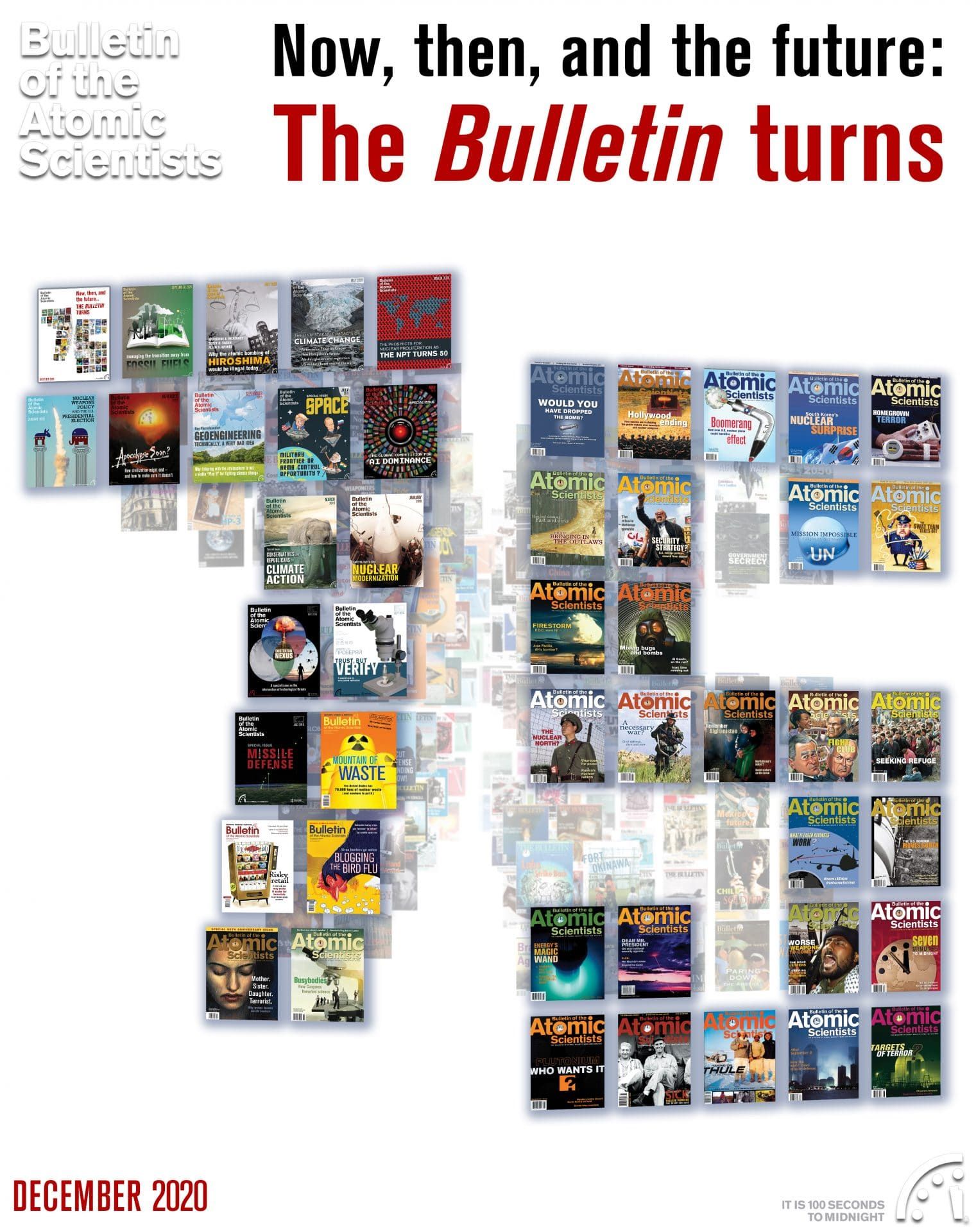

1992: Keep peace by pooling armies

By Randall Forsberg | December 7, 2020

1992: Keep peace by pooling armies

By Randall Forsberg | December 7, 2020

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in the May 1992 issue of the Bulletin, as part of a package on the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War. It is republished here as part of our special issue commemorating the 75th year of the Bulletin.

The end of the Cold War has opened the way to a cooperative security system that would minimize the role of armed force in international affairs. Over the next five to ten years, a four-part cooperative approach to security should aim to reduce nuclear forces to a minimum deterrent, reduce and restructure conventional forces to a “non-offensive defense” standard, stop the proliferation of offensive weapons systems and weapons industries, and replace unilateral military intervention with multilateral peacekeeping. Not surprisingly, these separate goals facilitate and reinforce each other.

In the longer term, a cooperative approach to international security should aim to abolish nuclear weapons and reduce conventional military forces to the scale of police forces.

In the longer term, a cooperative approach to international security should aim to abolish nuclear weapons and reduce conventional military forces to the scale of police forces.

Minimum nuclear deterrence: In a fully cooperative security system, the United States and the former Soviet Union would each cut back to a minimum deterrent initially comprising no more than 1,000 nuclear weapons and later no more than about 100. These arsenals would serve as a kind of “sea anchor” for peace, reminding all nations that war is no longer an acceptable means of achieving political or economic ends.

The longer-term objective would be to abolish nuclear weapons once it is clear that they no longer play a major role in deterring conventional war. Their irrelevance to issues of war and peace could be demonstrated in much the same way that the irrelevance of biological weapons was demonstrated in 1971, when President Richard Nixon ordered the Defense Department to abolish such weapons unilaterally, on the grounds that they were not usable instruments of war and their use would be heinous, regardless of the policies of other nations.

Non-offensive conventional defense: Over the next five to ten years, all the major industrial nations should make deep cuts in their conventional forces, shifting to small, stable non-offensive defenses with little capability for cross-border attack. At the same time, they should press and encourage all developing nations to make a comparable change. In the extreme case, this change would mean that all nations would cut back to nothing more than air defense, coastal defense, border guards, and national guard or internal security forces.

For the United States, cutting back to non-offensive defenses would be consistent with a policy shift from unilateral intervention to multilateral peacekeeping.

For all of the industrial nations, adopting non-offensive defenses would allow cuts in military spending on the order of 50 to 75 percent. In addition, switching to non-offensive defenses would facilitate establishing a ban on the production and export of high-tech, offensive conventional weapon systems.

In the third world, cutbacks to non-offensive defenses, combined with a ban on international trade in offensive systems, would save funds, reduce the risk of regional conflict, and facilitate multilateral peacekeeping.

Nonproliferation and arms export restraints: Using a combination of economic and diplomatic incentives and sanctions and a stringent export ban, the major industrial arms-producing nations should cooperate to stop the proliferation of offensive weaponry of all kinds-nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons, ballistic missiles, and high-tech conventional weapons with long-range offensive potential. Such proliferation is rapidly becoming the single greatest military threat to the industrial nations. The highest priority of their post-Cold War security policies should be to stop it.

Multilateral peacekeeping: The countries with the largest conventional forces—for example, the United States, the former Soviet Union, Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, and Japan among the industrial nations, and India, Egypt, and Brazil among the developing nations—should make a renewed commitment to support multilateral peacekeeping efforts approved by the U.N. Security Council (or for countries within a given region, peacekeeping efforts approved by comparable regional organizations such as the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe). Each country that has made such a commitment should keep, in addition to its national non-offensive defenses, small contingents of traditional ground, air, and naval forces earmarked for multilateral peacekeeping. Separately, these contingents should be too small to conduct a major war of aggression or intervention; combined, they should constitute a force large enough to stop an act of aggression or intervention by any single nation.

A security system based on non-offensive defense and multilateral peacekeeping would greatly strengthen efforts to stop the spread of nuclear weapons. The current nuclear powers initially acquired nuclear weapons to deter conventional war. Conventional arms races, along with the spread of conventional arms industries, are likely to cause more leaders to feel that they too need nuclear weapons to protect their nations from conventional attack and to preserve their national sovereignty.

Tactical attack aircraft offer a readily available delivery system for nuclear or chemical weapons and feed ambitions to acquire such weapons. The best hope for neutralizing these ambitions is for all nations to renounce large standing conventional forces, including large tactical air forces, previously maintained for deterrent or interventionary purposes. This would put the wealthy industrial countries in the position of playing by the same rules that they would like to see adopted in the Third World.

Nonproliferation efforts would also be strengthened by eliminating the several thousand nuclear warheads still maintained by the United States and the former Soviet Union for “extended deterrence,” which pose a clear risk of escalation from conventional to nuclear attacks on military targets. By clearly minimizing the role of nuclear weapons as a deterrent to conventional war, the two major nuclear powers would lessen the inclination of other nations to acquire nuclear weapons for this purpose.

There are three main obstacles to the wholesale change in security policy advocated here. One is a lack of widespread familiarity with the concept of non-offensive defense. A second is a lack of confidence in the viability of multilateral peacekeeping efforts to deal effectively with potential threats to peace. Both of these obstacles are likely to diminish over the course of the next decade, as new concepts are debated, more peacekeeping experience is gained, and confidence in the durability of the peace grows.

A third obstacle may be harder to overcome. This is the lack of high-powered conversion strategies and industrial policies that would provide a bridge from vastly reduced employment in the defense sector to comparable reemployment in civilian industries. During the current transition, it is most important to prevent conventional buildups in the Third World caused by exports from industrial nations that are anxious to keep factories open to keep production teams together and earn hard currency.

Short-sighted pressure to increase arms exports is likely to create new centers of military power, which would obstruct and complicate efforts to make the transition to a cooperative security system. We must not, for the sake of short-term economic interests, lose a unique opportunity to develop a demilitarized security system. We should do everything possible to keep open the option for this profound change, which would stop proliferation, save funds urgently needed for other purposes, and promote the development of democratic institutions.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Cold War, archive75, non-offensive defense, nuclear deterrence, nuclear disarmament

Topics: Nuclear Risk